Abstract

It is now well established that fossil fuel companies contributed to undermining climate science and action. In this paper, we examine the extent to which American electric utilities and affiliated organizations' public messaging contributed to climate denial, doubt, and delay. We examined 188 documents on climate change authored by organizations in and affiliated with the utility industry from 1968 to 2019. Before 1980, electric utilities' messaging was generally in-line with the scientific understanding of climate change. However, from 1990 to 2000, utility organizations founded and funded front groups that promoted climate doubt and denial. After 2000, these front groups were largely shut down, and utility organizations shifted to arguing for delayed action on climate change, by highlighting the responsibility of other sectors and promoting actions other than cleaning up the electricity system. Overall, our results suggest that electric utility industry organizations have promoted messaging designed to avoid taking action on reducing pollution over multiple decades. Notably, many of the utilities most engaged in communicating climate doubt and denial in the past currently have the slowest plans to decarbonize their electricity mix.

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

For decades, oil and gas companies have misled the public on climate science. Despite conducting their own research that showed climate change was real, these companies publicly sowed doubt about its existence and human cause (Oreskes and Conway 2010, Frumhoff et al 2015, Hall 2015, Supran and Oreskes 2017, Bonneuil et al 2021, Green et al 2021). While it is now well established that the fossil fuel industry undermined climate science, there is less research on other industries' role (Anderson et al 2017, Triedman et al 2019). In this paper, we examine the extent to which the American electric utility industry promoted climate denial, doubt, and delay.

In the 1960s and 1970s, fossil fuel companies and electric utilities knew that fossil fuel combustion was driving climate change, with many conducting in-house research on the issue (Hall 2015, Anderson et al 2017, Franta 2018). For example, the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) authored an internal memo in 1977 stating 'the atmospheric CO2 concentration is projected to double (to ≈600 ppm) by the year 2030. A simplistic climate model developed at Princeton predicts a 2 °C increase in the global mean temperature if CO2 is doubled' (Hakkarinen 1977, p 1). This prediction remains largely correct, more than four decades later. By the late 1980s, climate change was understood as real, human-caused, and serious. In 1988, when James Hansen testified to the U.S. Senate, climate change transitioned from a scientific discussion to a major policy issue (Frumhoff et al 2015, Bolsen and Shapiro 2018). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the leading body on climate science, published their first report in 1990, and stated with certainty that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions were contributing to climate change (IPCC 1990, p xi).

In response to the growing scientific consensus, organizations with financial interests in fossil fuels worked to discredit climate science and scientists, spread doubt, and delay the energy transition (Dunlap and McCright 2015, Farrell 2016, Brulle 2019). Sociologist Robert Brulle (2019) refers to this widespread disinformation campaign as the U.S. Climate Change Countermovement. An array of corporations, trade associations, lobbying firms, conservative think-tanks, and faith-based organizations collectively built climate disinformation campaigns. A variety of sectors participated, including the oil and gas industry, the coal-rail-steel sector, and the electric utility industry (Brulle 2019, Stokes 2020). These industries often created front groups in order to mask their involvement in spreading disinformation, motivated by their financial interests in fossil fuels (Brulle 2019, Dunlap and Brulle 2020, Stokes 2020). Climate denial, doubt, and delay have proven profitable for these sectors, allowing them to invest in polluting infrastructure for several decades longer than scientists have advised is safe (Tong et al 2019).

These industries' strategy to undermine climate science was developed from disinformation campaigns on acid rain and other environmental issues—campaigns that the utility industry also participated in (Oreskes and Conway 2010). For example, utility organizations ran ads in the 1970s and 1980s which largely acknowledged the link between sulfur dioxide and acid rain, yet misleadingly argued that pollution control technologies were infeasible and unnecessary (Anderson et al 2017). On climate change, politicizing scientific findings is the most well-documented tactic used in disinformation campaigns, including denying or sowing doubt regarding the existence, cause, or seriousness of the issue (McCright and Dunlap 2011, Farrell 2016, Supran and Oreskes 2017, Bolsen and Shapiro 2018, Franta 2021). Industries have also argued that they should delay taking action on reducing pollution, for example because solutions are too expensive, infeasible, or because others should be acting (Freudenburg 2005, Lamb et al 2020, Supran and Oreskes 2021). Collectively, disinformation campaigns affect media coverage, public opinion, and the likelihood of political action on climate, ultimately resulting in more greenhouse gas emissions due to political gridlock and inaction (Freudenburg and Muselli 2010, Farrell 2016, Bolsen and Shapiro 2018, Mildenberger 2020, Stokes 2020).

We undertook a systematic analysis of messaging on climate from members of the American electric utility industry over time. We collected and coded industry documents authored by individual electric utilities, trade associations, affiliated research groups, and front groups. Our sample includes 188 documents from 1968 to 2019. We classified statements regarding the existence, causes, and impacts of climate change, and its solvability, examining whether utility industry messaging diverged from the scientific consensus. We found that significant parts of the utility industry were active in promoting climate denial, doubt, and/or delay over multiple decades. Before 1980, electric utilities' messaging generally aligned with scientific knowledge at the time. However, from 1990 to 2000, utility organizations cast doubt on climate science, while simultaneously creating and funding front groups who promoted climate denial. Since many utilities are monopolies, these climate denial campaigns were often funded using money derived from captured customers, who could not choose to buy from a different company.

After 2000, many of the electric utility front groups were shut down, and official industry organizations largely shifted to arguing for delay. Since 2015, while much of the industry's messaging has largely acknowledged the scientific fact of climate change, delay messages are still common. Unlike fossil fuel companies, the electric utility industry's product is not fossil fuels. Clean energy coupled with electrification presents an opportunity for electric utilities to decarbonize and grow their business. To date, however, most of the industry has failed to do so at the pace and scale that is necessary. Notably, we also found that the utilities who were the most involved in promoting climate doubt and denial are also some of the dirtiest utilities operating today, with the slowest plans to transition to clean energy.

2. Methods

The American electric utility industry is made up of a variety of utilities including investor-owned, municipal, cooperative, and federal entities who produce and distribute electricity. These organizations coordinate through trade associations and other networks, including the Edison Electric Institute (EEI) and EPRI. EEI is the trade association for the investor-owned utilities. EPRI, 'incubated' under EEI and funded by the electric utility industry, is a non-profit energy research and development organization which conducts and publishes analyses, including on climate science and its implications for the sector (Lindgren 1972). In addition, some utilities have engaged with front groups, which are generally short-lived organizations designed to advance certain messaging while hiding their motives and funding sources (Brulle 2019, Dunlap and Brulle 2020, Stokes 2020).

We based our analysis on several samples of documents. First, we aimed to collect the known denial and doubt documents utility organizations and their affiliated front groups authored. This set was retrieved from the Climate Investigation Center, Climate Files, and an Energy and Policy Institute report (Anderson et al 2017). Some of these documents were public facing, while others were internal. To the best of our knowledge, for the two relatively short-lived denial front groups associated with the industry—the Information Council on the Environment (ICE) and the Greening Earth Society (GES)—all publicly available documents were included in the analysis.

For the longer-lived Global Climate Coalition (GCC), we built a temporally representative sample. We also examined membership lists for the GCC, and for those utilities frequently mentioned, we added additional documents from these companies, including shareholder reports (see supplementary Information, SI). Our aim was to understand how utilities associated with climate denial organizations were messaging externally on climate. In addition, we located documents and membership lists from utility-affiliated organizations who are or were associated with climate denial, doubt, and/or delay. These include the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), the Utility Air Regulatory Group (UARG), and American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity (ACCCE).

We also aimed to create a representative set of public facing documents on climate change from EEI and EPRI, with the goal of capturing overall industry messaging on climate. We drew a random sample of articles from these organization's periodicals, Electric Perspectives (1995–2019) and EPRI Journal (1976–2019), that mentioned the terms 'climate change', 'global warming', 'carbon dioxide', or 'greenhouse gas' (see SI).

Overall, this approach yielded 188 primary documents published between 1968 and 2019, authored by 26 organizations in the American electric utility industry (Williams et al 2021). Further information on the documents, including the temporal spread and a repository, is available in the SI. All documents reference climate change and are either authored by, or use direct quotes from, electric utility industry companies, research groups, trade associations, or other organizations which electric utilities founded or held membership.

Relationships between the organizations in the sample were mapped to understand their connections. To do this, we retrieved membership lists from the sample, two external reports (Anderson et al 2017, Triedman et al 2019), online repositories, and peer-reviewed research (Brulle 2019). In cases where the ownership or name of a utility changed, we use the current name and reference previous entities.

Notably, this approach is intended to ensure that utilities significantly involved in climate denial, doubt and/or delay are captured. Significant involvement is defined by membership in, funding of, or founding of climate front groups, or directly communicating climate doubt, denial, and/or delay. It therefore does not provide a representative sample of the full industry which could help determine the messaging of the average utility over time. That said, our sample of EEI and EPRI documents does provide representative information on how a central industry trade association and research group communicated about climate. In addition, some utilities that were found on membership lists for climate denial front groups were not examined further because there were no known denial or doubt documents authored by these organizations at the time of this analysis. Since many climate denial documents are internal, it is likely that further information exists on utilities' involvement in climate denial organizations that is not public.

The primary documents were coded using Atlas.TI, a qualitative analysis software. Documents were classified by author (the organization who authored the document), type (whether the document is internal or external), and year of publication. We developed a coding scheme modeled on the approach taken in Supran and Oreskes (2017) and incorporating discourses of climate delay introduced by Lamb et al (2020). We coded passages in the documents into categories based on their statements on climate change's existence (endorsement points, EPs), cause (human-caused points, HPs), impacts (impact points, IPs), and solvability (solvable points, SPs) (SI table 1). Each code category was designed to contain mutually exclusive levels (e.g. EP1, EP2, EP3).

Table 1. Climate messaging categories.

| Science Questions | Policy Questions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is the climate changing/projected to change? (Endorsement Points: EP) | Is human activity the primary cause of climate change? (Human-cause Points: HP) | Are the current or projected impacts of climate change serious? (Impact Points: IP) | Is climate change solvable? If so, does the industry have a responsibility to reduce emissions? (Solvable Points: SP) | |

| Acknowledgement: Document must acknowledge/endorse all science questions. | The climate is changing/projected to change (EP1). | Human activity is the primary cause of current or projected climate change (HP1) | The impacts of climate change are, or will be, primarily bad (IP1). | It is solvable, and the (partial) responsibility of utility companies (SP1). OR n/a. |

| Delay: Document must acknowledge/endorse all science questions. | The climate is changing/projected to change (EP1). | Human activity is the primary cause of current or projected climate change (HP1) | The impacts of climate change are, or will be, primarily bad (IP1). | More research is needed before taking action, it is the (primary) responsibility of another entity, or solutions must include continued use of fossil fuels (SP2). OR Climate change is not solvable (SP3). |

| Doubt: Document must doubt at least one science question. It may acknowledge the others. | The climate may be currently changing/may change in the future (EP2). | Human activity may be the cause of climate change (HP2). | The impacts may be bad (IP2). | n/a |

| Denial: Document must deny at least one science question. It may acknowledge or doubt the others. | The climate is (will) not changing (change) (EP3). | Human activity is not the cause of climate change (HP3). | The impacts do/will not exist, are overstated, or the benefits will outweigh the costs (IP3). | n/a |

Coding was conducted in two rounds; in each round, every document was coded independently by two separate coders. The first round of coding was at the document level, where relevant passages and code categories were identified for each document. In the second round, each passage was coded, and then document-level codes were assigned based on the frequency of passage-level codes used. If the document-level codes did not have inter-coder agreement (ICA), a third coder independently coded the document, and the most often applied code was ultimately assigned to the document. An ICA of 92% was reached for the EP, HP, and IP codes on the document-level codes, and an ICA of 88% was reached for the SP codes. Of the 188 documents analyzed, 151 were coded with at least one code—the remaining 37 documents mainly provided background information on the organizations.

Unique code combinations were reclassified into messaging categories: acknowledgement, delay, doubt, and denial (table 1). 'Acknowledgement' documents recognize that the climate is changing or will change (EP1), that human activity is the primary cause (HP1), and that impacts are primarily bad or unknown (IP1 or IP2). 'Doubt' documents convey uncertainty that the climate is changing or will change (EP2) and/or uncertainty as to whether human activity is the primary cause (HP2) and whether the impacts are serious (IP1 or IP2). 'Denial' documents either deny that the climate is changing or will change (EP3), deny that human activity is the primary cause of that change (HP3), or deny that there will be significant negative impacts (IP3). Finally, 'delay' documents acknowledge the scientific consensus (EP1, HP1, IP1/2), yet use rhetoric to deflect, delay, or distract from solutions (SP2/SP3).

3. Results

3.1. Mapping the network

Figure 1 and table 2 depict relationships between electric utility industry organizations and organizations that have promoted climate denial, doubt, and/or delay messaging. Electric utilities were related to three climate denial front groups: GCC, ICE, and GES. The GCC was one of the first and most prolific climate disinformation campaigns (Brulle 2019). It had strong links with the electric utility industry: EEI, American Electric Power (AEP), Consumers Energy, and Southern Company were co-founders of the GCC (see SI). Over a quarter of the GCC's members–and by extension funders–came from the industry, including the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA) (GCC 1991, Brulle 2019). Both EPRI and EEI were active participants in the GCC's Science and Technology Assessment Committee meetings (GCC 1997).

Figure 1. Organizational network map depicting relationships between utility trade groups, research groups, front groups, and campaigns in the document sample. Solid arrows indicate an organization founded, and was a member of and/or participated in meetings and communications of another; dashed arrows indicate an organization was a member of and participated in meetings or communications of another; gray dotted lines indicate organizations participated in meetings or communications together.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 2. Utilities' involvement in CCCM organizations in figure 1 and measures of pollution for these utilities. All depicted UARG links are valid for 2017. ICE membership is fully inclusive to the best of our knowledge. All links for GCC, ALEC, and ACCCE are included, regardless of year of involvement. Utility organization involvement in GCC varies across years (see SI). For ALEC and ACCCE, since these organizations do not make their membership public, a lack of reported connection does not mean no connection exists, but that no connection was identified in this research.

| ACCCE | ALEC | GCC | ICE | UARG | Climate Score based on plans | Standardized emissions (lbs CO2/MWH) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Company | Member | Member | Founder, member | Member | Member | 5 | 1000 |

| American Electric Power (AEP) | Member | Sponsor, member | Founder, member | Member | 29 | 1500 | |

| Ameren (formerly Union Electric and Illinois Power) | Member | Sponsor, member | Member | Member | 24 | 1500 | |

| Duke | Member | Sponsor, member | Member | Member | 2 | 900 | |

| Arizona Public Service (APS) (Pinnacle West) | Funder, member | Member | Member | Member | 34 | 1000 | |

| DTE Energy (formerly Detroit Edison) | Member | Member | Member | 22 | 1500 | ||

| FirstEnergy (formerly Ohio Edison and Pennsylvania Power) | Member | Member | Member | 0 | 1000 | ||

| Consumers Energy | Member | Founder, member | Member | 43 | 1750 | ||

| Dominion (formerly Virginia Power) | Member | Member | Member | 27 | 600 | ||

| Northern Indiana Public Service Company (NIPSCO) (NiSource) | Sponsor | Member | Member | 82 | 1800 | ||

| Entergy | Sponsor, member | 33 | 600 | ||||

| Southern California Edison (SCE) | Member | Not in the 50 dirtiest utilities | 400 |

a ACCCE (2018). b Smyth (2016). c DeSmog (2022a). d SourceWatch (2022). e See SI. f Information Council for the Environment (1991). g Utility Air Regulatory Group (2017). h Romankiewicz et al (2020). i Bradley (2021).

ICE was a short-lived, pilot climate denial campaign, whose primary goal was to '[r]eposition global warming as theory (not fact)' through both print and radio advertisements (ICE 1991, p 7). This campaign was co-founded by EEI and the Western Fuels Association (WFA), which is a utility association composed of coal providers and rural electric cooperatives (Monbiot 2009, Mulvey and Shulman 2015, DeSmog 2022b). Individual utilities were also involved in ICE, including Southern Company as a funder of ICE, and Arizona Public Service (APS)—though APS 'reserve[d] the right to distance' themselves from ICE activities (Information Council for the Environment 1991, p 5, 8). With the collapse of ICE, WFA next founded GES in 1997, a campaign which operated until 2005 (GES 2005). GES similarly produced print advertisements and videos that undermined climate science.

In addition to founding and participating in climate denial front groups, utility industry organizations have also lobbied against climate legislation while promoting messages of denial, doubt, and delay. Work to delay climate action has primarily occurred through three organizations: ALEC, the UARG, and America's Power. Founded in 1973, ALEC brings together corporate interest groups with conservative state legislators. It writes model legislation on a range of issues, including rolling back renewable energy laws (Stokes 2020). As of 2022, it continued to promote climate denial, stating: 'Global Climate Change is Inevitable. Climate change is a historical phenomenon and the debate will continue on the significance of natural and anthropogenic contributions' (ALEC 2022). While its membership is not publicly shared, documents show numerous utilities were members and funders of ALEC over the years (Anderson et al 2017, ALEC 2018, Triedman et al 2019, Energy and Policy Institute 2022, DeSmog 2022b). As of 2019, Duke, APS, NRECA, and EEI were still participating in ALEC meetings (Surgey 2019).

The UARG was a utility association founded in the 1970s to resist Clean Air Act regulations (Lazarus 2020). It filed numerous lawsuits and comments on behalf of electric utilities to fight climate policy, at times promoting climate doubt, before dissolving in 2019 (UARG 2009, Kasper 2021). Many utilities terminated their membership in UARG during a congressional investigation that showed ratepayer funds were used to support this climate delay organization. For example, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) used millions of dollars of customer revenues over several decades to fund UARG lawsuits blocking climate action (Kasper 2021; e.g. UARG 2017). However, despite the controversy, several utilities and associations remained members of UARG until its dissolution in 2019, including EEI, AEP, Ameren, FirstEnergy, TVA, and Southern Company (Bade 2019, Kasper 2019).

America's Power, formerly known as the ACCCE, is a pro-coal advocacy organization that has lobbied heavily against climate legislation (Anderson et al 2017, Brulle 2019). ACCCE led the effort to rebrand coal, pushing the image of 'clean coal' and emphasizing the 'social benefits of carbon' (Management Information Services 2014, Anderson et al 2017). At its peak, it derived half of its members from the electric utility industry (Brulle 2019). While Ameren, FirstEnergy, Duke, and DTE Energy left ACCCE before 2016, AEP and Southern Company stayed until 2019 (Smyth 2016, ACCCE 2018, Energy and Policy Institute 2022).

Table 2 summarizes the relationships identified in our sample between individual electric utilities and these groups; the table is ordered by frequency of involvement. The utilities listed in the table were all authors of documents in the sample or listed regularly in GCC membership lists (see SI). All electric utilities in table 2 are members of EPRI and EEI (EPRI 2006, EEI 2019). As formal membership lists are not available for ALEC and ICE, we detail contributions, coordination, or otherwise documented cooperation. Ten utilities stand out as being extensively involved in climate denial, doubt, and delay. These utilities had documented participation or membership in three or more known climate denial, doubt and/or delay organizations: Southern Company, AEP, Ameren, Duke, APS, DTE, FirstEnergy, Consumers Energy, Dominion, and Northern Indiana Public Service Company (NIPSCO).

Notably, many of the ten utilities most extensively involved in climate denial stand out as the largest polluters in the industry today. Table 2 summarizes two measures of pollution for these utilities (see SI for details on these measures). The climate score is based on the 50 dirtiest utilities' plans to retire coal, build new gas capacity, and build clean energy infrastructure (Romankiewicz et al 2020). Nine out of ten utilities who were extensively involved in promoting climate denial, doubt and delay have poor climate plans. A second score, developed with two major utilities, shows current standardized emissions in CO2/megawatt-hour (MWH) for the utilities in our sample (Bradley 2021). Here again, the ten utilities extensively involved in climate denial generally stand out as some of the dirtiest in the industry today. This suggests that utilities with significant investments in fossil fuels promoted climate denial based on their material interests.

3.2. Tracing the utility industry's messaging on climate change over time

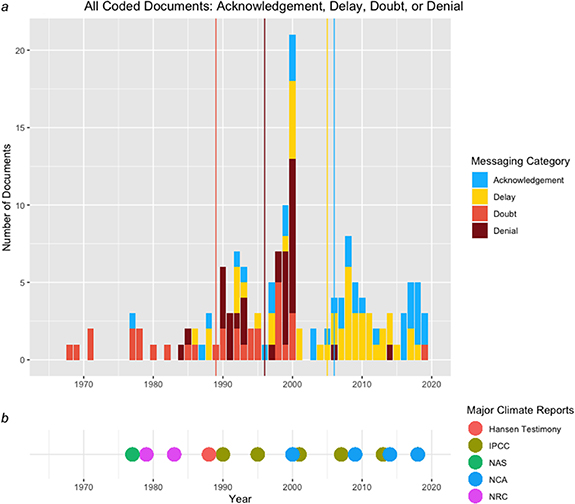

Using our document sample, we examine how the utility industry messaged on climate change over time. If their public communications tracked with the scientific consensus, we should not expect to find evidence of doubt regarding the existence and cause of climate change after 1990 at the latest. The utility industry was aware of the climate science developments of the 1980s, having conducted some of its own research. However, our analysis indicates that the industry communicated climate denial and doubt throughout the 1990s, after the scientific consensus was established (figure 2(a)). Doubt was most common in the early part of the study period, when the scientific consensus on human-caused climate change was still emerging. As such, a degree of uncertainty during this time could be considered reasonable. However, nearly half of the doubt documents in our sample are found after Hansen's 1988 testimony (figure 2(b)). In addition, denial documents are centered in 1996, indicating an industry-wide shift from doubt to denial during the time the scientific consensus on climate change became public. In other words: as science increasingly showed climate change existed and was human caused, some utility industry organizations shifted increasingly toward climate denial.

Figure 2. Temporal distribution of categorized codes for all documents (a). Taking the average year for documents in each messaging category, acknowledgement documents are centered in 2006, delay documents are centered in 2005, doubt documents are centered in 1989, and denial documents are centered in 1996 (years indicated as vertical lines). Major climate reports are shown (b) from the IPCC (olive), National Climate Assessment (blue), National Research Council (magenta), National Academies of Science (green), and Hansen congressional testimony (red).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageAfter 2000, the documents indicate an industry-wide shift towards communicating delay. During this time, while most (95%) documents implicitly or explicitly acknowledged that climate change existed and was human-caused, over half of the documents contained 'delay' rhetoric, deflecting responsibility onto other countries or sectors, or arguing for the necessity of continued reliance on fossil fuels for electricity generation. The only organizations in the sample communicating denial or doubt after 2000 were CORE Electric Cooperative (formerly intermountain rural electric association, or IREA, in 2005), ACCCE (in 2014), and ALEC (in 2019) (figure 2(a)).

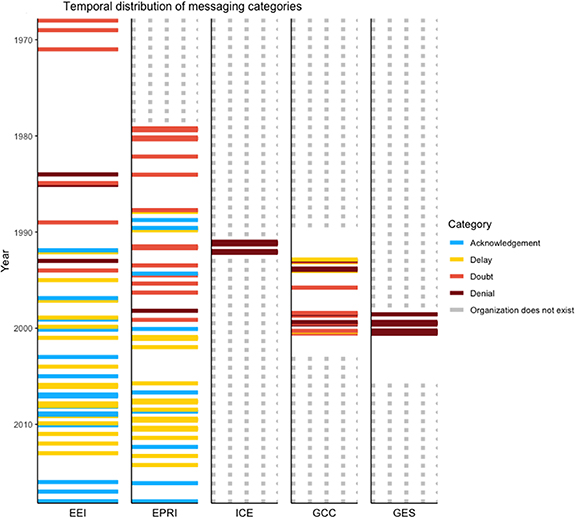

While patterns exist for the utility industry in our sample (figure 2), messaging varied by organization. To examine how individual organizations within the utility industry communicated publicly about climate change, we examined documents from the five primary organizations in our sample (figure 3). Comparison across all five organizations is only possible in the 1990s, when all were active. From 1990 to 2000, both EPRI and EEI had mixed communications that mostly included doubt, with some denial, delay, and even acknowledgment. However, during this same period, the front groups that were funded and/or otherwise supported by the industry—GCC, ICE, and GES—all spread climate doubt and denial. As ICE and GCC were cofounded by EEI (figure 1), this demonstrates that electric utility industry organizations, like their counterparts in the oil and gas industry, used front groups to undermine climate science. These front groups were short-lived, all dissolving around 2000; after 2000, official industry organization messaging transitioned to a mix of acknowledgement and delay.

Figure 3. Temporal distribution of categorized codes for the five primary organizations in the sample. Years before an organization's founding or after its dissolution are shown in gray. Thick lines represent multiple documents, while thin lines represent a single document.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image3.3. Examining EEI and EPRI's climate messaging over time

Our sample includes a representative set of documents from EEI and EPRI, two important organizations within the electric utility industry. In this section, we unpack both organizations' messaging on climate change over the past 50 years in greater detail. We identify certain patterns in messaging in our representative sample of EEI and EPRI's journals. Before 1990, both organizations communicated doubt about climate change (figure 3). Yet, even after the scientific consensus crystalized, in the 1990s, both organizations continued to communicate denial, doubt, and delay. After 2000, both EEI and EPRI have alternated between delay and acknowledgement.

In the 1970s, both EEI and EPRI recognized that if climate change was real and human-caused, the implications for the industry would be enormous. A 1977 EPRI Journal article stated: 'if [climate change turned] out to be of major concern, then fossil fuel combustion will be essentially unacceptable' (Comar 1977, p 14). EEI's bulletin published a similar article in 1971: '[i]f we had to stop producing CO2, no coal, oil, or gas could be burned... The only possible alternative is nuclear energy...' (Wilson 1971, p 181). While EPRI and EEI documents from the 1970s emphasize uncertainties in climate science, they also stated that action should not be delayed given serious climate impacts. One EPRI Journal article ended by quoting scientist William Kellog: 'If we wait to let the atmosphere perform the carbon dioxide experiment...it will be too late to do much about it if a warmer earth should prove to be a sadder earth' (Terra 1978, p 27).

In the 1980s, EPRI and EEI messaging continued to grapple with climate science uncertainty yet argued increasingly for delay. One EPRI article from 1986 presented a range of views from 'we have to conduct a lot more scientific research before we do anything else' to 'we do know enough to mitigate the greenhouse effect' (Shepard 1986, pp 13–15). That same year an EPRI Journal editorial argued that the 'decision will be easier to make and will be better designed if we know more about the science of the issue' (Malès 1986, p 2). Similarly, a 1989 EEI article stated: 'any plan calling for urgent and extreme action to reduce utility CO2 emissions is premature at best' (McCollam 1989, p 44). Articles began emphasizing the global nature of the climate problem and the emissions of developing countries. They argued the U.S. electricity industry was only a small percentage of global emissions. For example, a 1988 EPRI article stated that: '...the United States cannot solve the greenhouse problem alone. It is a global issue...Of the U.S. contribution to CO2 loading, about one quarter comes from electric utilities... U.S. and Western European fossil fuel CO2 emissions have been fairly stable since the early 1970s, but emissions from the eastern bloc, China, the Pacific Rim, and developing nations are rising...' (EPRI 1988, pp 14–15). In fact, while U.S. CO2 emissions in 1988 were only marginally higher than in the 1970s, emissions had been steadily increasing since the early 1980s, and continued to increase until 2007 (Ritchie et al 2020). By 1990 the American electricity sector was almost 7% of total global carbon pollution—a significant share (Global Carbon Project 2020, EPA 2021).

By the 1990s, climate science had established that climate change was real and human caused. During this decade, a divergence occurred between the two organizations: EPRI continued to communicate doubt throughout the decade, while EEI increasingly promoted delay (figure 3). As the research arm for the industry, EPRI articles discussed the science of climate change more than EEI articles, while EEI generally discussed policy implications, likely explaining this difference in the organizations' messaging. However, both organizations also each published a denial document, both arguing that climate impacts were not serious. An EEI article asserted that the data 'show cooler days, warmer nights, and better vegetables' (Michaels 1993, p 1), while an EPRI article stated that 'aggregate damages to the U.S. economy are likely to be substantially lower than previously estimated, with some sectors realizing net benefits' (Wilson and Pietka 1997).

In the mid-1990s, EEI also began advocating for voluntary action rather than binding policy (Draper 1994, EEI 1999). As the Kyoto Protocol negotiations unfolded, the industry argued that the U.S. should not reduce emissions if other countries continued to emit. EEI stated that targets in the Kyoto Protocol were 'unrealistic' (Novak 2001, p 68) because the renewable energy required by 'even the most modest climate treaty proposal' would leave the electricity sector unable to meet current U.S. energy demand (EEI 1997, p 78). Instead, EEI's stance at the turn of the century was that to '[stabilize] atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases cost-effectively over the long term...we should focus our near-term efforts on conducting an accelerated climate technology research, development, and deployment program' (Novak 2001, p 68). This push for R&D and voluntary initiatives has continued to the present, defining much of the industry's stance on climate action in the 2000s.

By the 2000s, EEI and EPRI no longer communicated doubt or denial; instead, both frequently argued to delay transitioning the electricity mix (figure 3). Language deflecting focus onto the emissions of other countries and sectors was still used in EPRI and EEI documents in the early 2000s, though less than in the prior two decades. Instead, after 2000, EEI and EPRI frequently presented carbon capture and storage (CCS) as the most promising solution to climate change, arguing that because 'half of U.S. electricity comes from coal combustion, any policy to reduce electricity's carbon footprint will rely on carbon capture and storage' (EPRI 2010, p 10). As such, these documents argued that climate action must focus on pursuing 'clean coal' via gasification and CCS. In our representative sample of EEI and EPRI documents from 2000–2019, 'clean coal' and CCS were discussed as much as all other carbon-free technologies combined (word count: CCS and integrated gasification combined cycle, or IGCC, N = 658; renewable, solar, wind, geothermal, and nuclear, N = 654). While most current electricity decarbonization scenarios include some form of CCS, the technology is predicted to account for less than 5% of total generation by 2040 (Larson et al 2020, IEA 2021, Williams et al 2021). Instead, these studies identify renewables, energy efficiency, and electrification as the primary solutions. Moreover, CCS has struggled technologically and financially: after more than 40 years of effort, CCS remains expensive (Jarratt and Coates 1984, Shepard 1986, Hannegan 2011, Abdulla et al 2020). Overall, 90% of the proposed power sector CCS capacity was never built (Abdulla et al 2021). As of 2021, there are no commercial-scale CCS facilities in the American power sector (Global CCS Institute 2021).

Only in the last few years have EEI and EPRI more consistently acknowledged the scientific consensus on climate change and the need to transition away from fossil fuels. After 2015, all EPRI and EEI documents in our sample communicated acknowledgement. That said, in 2017, the current CEO of Southern Company and then chairman of EEI stated in a television interview that he did not believe human activity was causing climate change. When asked, 'Do you think it is been proven that CO2 is the primary climate control knob?', he replied 'No. Certainly not. Is climate change happening? Certainly. It is been happening for millennia...' (Belvedere 2017). This is climate denial.

4. Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we have examined a cross section of the American electric utility industry's public messaging on climate change. While industry organizations knew about, and in some cases conducted research on, climate science as far back as the 1970s, until 2000 some utility organizations in this analysis cast doubt on climate change and founded, funded, and engaged in disinformation campaigns. Their actions were not limited to messaging alone: the utility industry spent over $500 million lobbying against renewable energy and climate policy over the past two decades (Brulle 2018, Mildenberger 2020, Stokes 2020).

After 2000, while EEI and EPRI no longer publicly doubted or denied climate change, these organizations continued to argue for delayed action. This rhetoric deflected focus onto other countries and sectors and uplifted approaches such as CCS that have proven unviable to date in the power sector, distracting attention from the energy transition. This shift from doubt to delay is the same pattern that was identified in ExxonMobil's communications (Supran and Oreskes 2021).

Yet, unlike fossil fuel companies, the electric utility industry does not have to continue to rely on fossil fuels to produce electricity. Technologies exist today to decarbonize much of the sector by 2035 (Phadke et al 2020). Coupling clean electricity with electrification of transportation, buildings, and industry has the potential to eliminate the majority of American carbon pollution, and has been shown to be a cost-effective pathway (Luderer et al 2022). This pathway would even prove profitable for the electric utility sector (Stokes 2020). Increasingly, the industry is realizing the opportunity in clean energy and electrification. For example, in 2018, the CEO of Southern California Edisons holding company wrote in EEI's Electric Perspectives: 'We need myriad resources and stakeholders to address climate change, but I believe electric companies are central figures. Only electric companies have the size and resources to implement clean energy initiatives on a significant scale' (Pizarro 2018, p 30). Furthermore, two of the ten utilities that we find were the most involved in climate denial, doubt and delay—NIPSCO and Consumers Energy—have significant plans to transition their dirty assets to clean resources this decade (Romankiewicz et al 2020, Stokes 2020).

However, others are continuing to delay. As of 2020, the 79 utilities that generated a majority of U.S. electricity from fossil fuels had only pledged to retire a quarter of their coal generation by 2030, while proposing over 36 GW of new gas plants. These same utilities had only pledged to replace 19% of their current fossil generation with renewable resources (Romankiewicz et al 2020). As a whole, the electric utility industry is moving too slowly on transitioning to clean energy. Of the ten utilities we identify as most involved in climate denial, doubt and delay, eight are delaying acting on clean energy: Southern Company, AEP, Ameren, Duke, APS, DTE, FirstEnergy, and Dominion (Romankiewicz et al 2020). These eight utilities remain heavily invested in dirty energy with few plans to transition to clean power. Similarly, Galli Robertson and Collins's (2019) found that Southern Company, AEP, and Duke—three of the utilities most involved in climate denial—are among the seven largest emitters in the industry, accounting for >25% of coal fired electricity generation emissions. Hence there is a tight correlation between those utilities that are maintaining fossil fuel assets today and those that have promoted climate denial, doubt, and delay.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Energy and Policy Institute for providing documents and advice. This research was financially supported by the Rockefeller Family Fund.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the following URL/DOI: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RVFTCP. Data will be available from 8 September 2022.

Author contributions

E W: Conceptualization (equal), data curation (equal), formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, software, validation, visualization, writing (lead); S B: Data curation (equal), formal analysis, investigation, validation, writing (supporting); E S: Data curation (equal), formal analysis, investigation, validation, writing (supporting); L S: Conceptualization (equal), funding acquisition, methodology, supervision, writing (lead)

Supplementary data (0.1 MB PDF)