Abstract

Dusty circumnuclear disks (CNDs) in luminous early-type galaxies (ETGs) show regular, dynamically cold molecular gas kinematics. For a growing number of ETGs, Atacama Large Millimeter/sub-millimeter Array (ALMA) CO imaging and detailed gas-dynamical modeling facilitate moderate-to-high precision black hole (BH) mass (MBH) determinations. From the ALMA archive, we identified a subset of 26 ETGs with estimated MBH/M⊙ ≳ 108 to a few × 109 and clean CO kinematics but that previously did not have sufficiently high-angular-resolution near-IR observations to mitigate dust obscuration when constructing stellar luminosity models. We present new optical and near-IR Hubble Space Telescope (HST) images of this sample to supplement the archival HST data, detailing the sample properties and data-analysis techniques. After masking the most apparent dust features, we measure stellar surface-brightness profiles and model the luminosities using the multi-Gaussian expansion (MGE) formalism. Some of these MGEs have already been used in CO dynamical modeling efforts to secure quality MBH determinations, and the remaining ETG targets here are expected to significantly improve the high-mass end of the current BH census, facilitating new scrutiny of local BH mass–host galaxy scaling relationships. We also explore stellar isophotal behavior and general dust properties, finding these CNDs generally become optically thick in the near-IR (AH ≳ 1 mag). These CNDs are typically well aligned with the larger-scale stellar photometric axes, with a few notable exceptions. Uncertain dust impact on the MGE often dominates the BH mass error budget, so extensions of this work will focus on constraining CND dust attenuation.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

Supermassive black holes (BHs), spanning a mass range of ∼105–1010 M⊙, are believed to be at the centers of nearly all large galaxies (i.e., M⋆ > 1011 M⊙; McConnell & Ma 2013). Over the past two decades, dynamical modeling techniques have been employed to measure BH masses (MBH) in well over 100 galaxies (e.g., Kormendy & Ho 2013; Saglia et al. 2016). Although BHs gravitationally dominate only the innermost regions of their host galaxies (often not more than the central few parsecs to few hundreds of parsecs in extreme cases), their masses strongly correlate with several large-scale galaxy properties, especially the stellar bulge velocity dispersion (σ⋆; e.g., Ferrarese & Merritt 2000; Gebhardt et al. 2000) and luminosity or mass (Lbul or Mbul; e.g., Kormendy & Richstone 1995; McConnell & Ma 2013). Such empirical relations suggest a coevolution of the central BH and its host galaxy through a series of gas accretion and galaxy-merger events across cosmic time. During this galaxy growth, star formation and BH accretion are regulated by both stellar and active galactic nucleus (AGN) feedback processes. However, the detailed nature of these scaling relationships—including the intrinsic scatter and dependence on galaxy morphology—remain uncertain due to small sample size, some poorly constrained MBH values, and persistent selection biases.

For the most luminous early-type galaxies (ETGs; encompassing both lenticular S0 and elliptical E galaxies), including several brightest group galaxies (BGGs) and brightest cluster galaxies (BCGs) with cored stellar surface-brightness profiles, current data hint at a steeper MBH–σ⋆ slope (Bernardi et al. 2007; Lauer et al. 2007; McConnell & Ma 2013). This result suggests that BH growth in high-galaxy-density environments follows a different evolutionary path due to the prevalence of dry (gas-poor) mergers in clusters and to a lesser extent in groups (see, e.g., Bogdán et al. 2018). However, the BH census remains incomplete above ∼108.7 M⊙, and statistical mass uncertainties in this regime are typically large (of order 25%; e.g., Saglia et al. 2016). In addition, potentially serious (and often unexplored) systematics in both stellar and gas-dynamical models may affect MBH measurements (for more discussion, see Kormendy & Ho 2013). For example, stellar triaxality is infrequently incorporated into stellar-dynamical modeling (see Liepold et al. 2023), possibly biasing the best-fitting MBH by a factor of 2 in some cases (van den Bosch & de Zeeuw 2010). A larger sample of MBH for luminous ETGs, together with greater measurement precision, are necessary for any confident interpretation of BH–host galaxy coevolution in rich galaxy environments. The most reliable MBH determinations originate from spatially resolved, relaxed tracer kinematics that extend well within the BH sphere of influence approximated by , within which the BH's gravitational influence dominates over the galaxy's extended mass contributions.

Dense molecular gas in circumnuclear disks (CNDs) provides an appealing avenue for expanding the high-mass BH census with higher precision than typically possible through other techniques. Because of the small physical extent of these CNDs (dust radii of ∼100 pc to a few kiloparsecs for most ETGs; Tran et al. 2001), gas-dynamical modeling processes are less sensitive to uncertainties in large-scale galaxy properties that often hamper stellar-dynamical efforts (e.g., van den Bosch & de Zeeuw 2010; McConnell & Ma 2013). Extended atomic/molecular gas and dust are detected in roughly half of all ETGs (di Serego Alighieri et al. 2007; Young et al. 2011; Serra et al. 2012; Alatalo et al. 2013), with an apparent preference for dense molecular gas to be found in lenticular as opposed to elliptical galaxies (di Serego Alighieri et al. 2013). About 10%–20% of all ETGs host morphologically round CNDs that suggest significant molecular gas in dynamically cold rotation which should be amenable to gas-dynamical modeling (e.g., Lauer et al. 2005; Maiolino 2008; Davis et al. 2011; Alatalo et al. 2013). In some CNDs, these tracer kinematics are detected down to (or even well within) rg, making them appealing targets for constraining BH masses.

Resolved low-J CO imaging using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) has already mapped molecular gas kinematics in a few dozen ETGs with dusty CNDs (e.g., Boizelle et al. 2017; Ruffa et al. 2019b; Zabel et al. 2019). This effort is especially valuable for the most luminous dust-disk ETGs, which tend to have large physical rg but are expected to have at least mildly triaxial stellar structures that make global stellar-dynamical modeling challenging. In cases with relaxed gaseous kinematics probing near or within rg, gas-dynamical modeling of CO cubes has resulted in some of the most precise BH mass measurements to date (Barth et al. 2016a, 2016b; Davis et al. 2017, 2018; Onishi et al. 2017; Boizelle et al. 2019, 2021; North et al. 2019; Smith et al. 2019, 2021a; Cohn et al. 2021, 2023; Ruffa et al. 2023). In addition to those cases, a greater number of ETGs have ALMA CO imaging with synthesized beam FWHMs θFWHM ≲ 2rg that should enable good-quality MBH determinations (Davis 2014).

In addition to the quality and coverage of the tracer kinematics, the accuracy of both stellar and gas-dynamical models relies on an accurate model of the galaxy mass as a function of radius. In most cases, the gas masses of CNDs in luminous ETGs are in the range ∼105–109 M⊙ (e.g., Young et al. 2011; Boizelle et al. 2017; Ruffa et al. 2019b), with the result that the enclosed mass profile is dominated by the stellar component from ∼rg out to at least a few half-light radii (Re). Models of a galaxy's mass profile are typically derived from two-dimensional (2D) optical/near-IR images of the observed stellar surface brightnesses, typically at an angular resolution similar to rg (or at least θFWHM for the ALMA CO kinematics) to avoid potentially biasing the MBH value (Yoon 2017).

Unfortunately, previous optical/near-IR imaging did not always have sufficient angular resolution to be fully useful in ALMA CO dynamical modeling efforts for luminous galaxies. At typical distances of 20−50 Mpc, these CNDs subtend angular sizes of only a few arcseconds or less, with the typical rg of the host BH on the order of ∼0 05–1

05–1 0. These CND systems are therefore difficult to resolve and study at optical/near-IR wavelengths except with the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), or large-aperture ground-based facilities with adaptive optics capabilities. In addition, for certain ETGs the dust accompanying large CO column densities is sufficiently opaque, extended, and/or face-on to limit the usefulness of optical HST imaging when constructing stellar mass models. The intrinsic CND dust extinction is not known a priori, but studies have demonstrated peak AV

∼ 3–5 mag extinction of the background stellar light in some cases (e.g., Ferrarese et al. 1996; Viaene et al. 2017; Boizelle et al. 2019, 2021; Cohn et al. 2021, 2023; Kabasares et al. 2022) that is much higher than foreground screen estimates (e.g., Tran et al. 2001). Due in large part to exquisite CO kinematics, select ALMA studies have demonstrated that uncertainty in the dust-extinction correction tends to be the dominant term in the BH mass error budget (Boizelle et al. 2019, 2021; Cohn et al. 2021; Kabasares et al. 2022).

0. These CND systems are therefore difficult to resolve and study at optical/near-IR wavelengths except with the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), or large-aperture ground-based facilities with adaptive optics capabilities. In addition, for certain ETGs the dust accompanying large CO column densities is sufficiently opaque, extended, and/or face-on to limit the usefulness of optical HST imaging when constructing stellar mass models. The intrinsic CND dust extinction is not known a priori, but studies have demonstrated peak AV

∼ 3–5 mag extinction of the background stellar light in some cases (e.g., Ferrarese et al. 1996; Viaene et al. 2017; Boizelle et al. 2019, 2021; Cohn et al. 2021, 2023; Kabasares et al. 2022) that is much higher than foreground screen estimates (e.g., Tran et al. 2001). Due in large part to exquisite CO kinematics, select ALMA studies have demonstrated that uncertainty in the dust-extinction correction tends to be the dominant term in the BH mass error budget (Boizelle et al. 2019, 2021; Cohn et al. 2021; Kabasares et al. 2022).

To facilitate more accurate BH mass measurements derived from ALMA CO data, we developed a set of HST programs to obtain new broadband imaging for ETGs with the most promising ALMA CO emission-line data sets. This sample included candidates with large rg and relatively small ALMA θFWHM, together with regular CO kinematics, but having no near-IR (or, at times, even optical) HST imaging. In this paper, we focus on constructing stellar luminosity models that can be employed in ongoing ALMA CO modeling efforts or in future gaseous/stellar-dynamical modeling. We additionally explore analyses of the stellar surface brightness and color behavior of the near-IR data to better place these targets in the context of volume-limited surveys. Our HST programs also include supplementary optical data that are needed to map dust attenuation, but we defer that analysis to a future paper.

This paper is organized as follows. In Sections 2 and 3, we introduce the ETG sample and describe the new and archival optical/near-IR observations, respectively. In Section 4, we explore the isophotal and color behavior of these galaxies. We detail the construction of stellar luminosity models using the multi-Gaussian expansion (MGE) formalism in Section 5. In Section 6, we discuss these results in the context of past work and analyze the accuracy and consistency of these MGE solutions. In Section 7, we preview next steps and discuss conclusions. Throughout this paper, we adopt a standard Lambda cold dark matter (ΛCDM) cosmology with Ωm = 0.308, Ωvac = 0.692, and Hubble constant H0 = 73 km s−1 Mpc−1 (Blakeslee et al. 2021; Kenworthy et al. 2022; Riess et al. 2022). Magnitudes are in the Vega system.

2. ETG Sample

We identified targets for this project based on the existence of CO(1−0), CO(2−1), and/or CO(3−2) imaging of ETGs in ALMA Cycles 2−5. Selection criteria were designed to ensure that current (or future) ALMA CO imaging could enable high-confidence MBH constraints. To that end, we selected systems with very regular CO kinematics and θFWHM ∼ 0 1–0

1–0 6 to ensure well-resolved disks. This was done by analyzing currently unpublished pipeline-calibrated images from the ALMA archive (B. D. Boizelle et al. 2024, in preparation) or by looking to literature sources to help identify additional targets with regular CO kinematics (Boizelle et al. 2017, 2021; Davis et al. 2017, 2022; van de Voort et al. 2018; Babyk et al. 2019; Rose et al. 2019; Ruffa et al. 2019a, 2019b, 2023; Zabel et al. 2019; Kabasares et al. 2024). Next, we selected ETGs with estimated rg ≳ 0

6 to ensure well-resolved disks. This was done by analyzing currently unpublished pipeline-calibrated images from the ALMA archive (B. D. Boizelle et al. 2024, in preparation) or by looking to literature sources to help identify additional targets with regular CO kinematics (Boizelle et al. 2017, 2021; Davis et al. 2017, 2022; van de Voort et al. 2018; Babyk et al. 2019; Rose et al. 2019; Ruffa et al. 2019a, 2019b, 2023; Zabel et al. 2019; Kabasares et al. 2024). Next, we selected ETGs with estimated rg ≳ 0 09 (using measured central σc and MBH estimated from the MBH–LK

scaling relation; Kormendy & Ho 2013) to ensure that rg could be fully resolved, perhaps using a more extended ALMA configuration in a reasonable amount of time. This led to a natural cutoff for distances D ≳ 250 Mpc or redshifts z ≳ 0.06. All targets have an expected CND radius ≳0

09 (using measured central σc and MBH estimated from the MBH–LK

scaling relation; Kormendy & Ho 2013) to ensure that rg could be fully resolved, perhaps using a more extended ALMA configuration in a reasonable amount of time. This led to a natural cutoff for distances D ≳ 250 Mpc or redshifts z ≳ 0.06. All targets have an expected CND radius ≳0 5 to allow for spatial characterization of the CND dust properties. Lastly, we removed candidates with previous HST wide-field, broadband near-IR (e.g., F110W) imaging to focus on cases that would benefit the most from additional HST data. Previous Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrograph (NICMOS; Dickinson et al. 2002) data sets had too narrow a field of view (FOV) to build reliable stellar luminosity models, so we included several HST NICMOS-observed ETGs in our sample.

5 to allow for spatial characterization of the CND dust properties. Lastly, we removed candidates with previous HST wide-field, broadband near-IR (e.g., F110W) imaging to focus on cases that would benefit the most from additional HST data. Previous Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrograph (NICMOS; Dickinson et al. 2002) data sets had too narrow a field of view (FOV) to build reliable stellar luminosity models, so we included several HST NICMOS-observed ETGs in our sample.

The final sample containing 26 ETGs is listed in Table 1 and compared to two surveys of local ETGs in Figure 1. This sample, containing about 42% elliptical and 58% lenticular galaxies, is not entirely representative of the local population of luminous ETGs, although it does span Ks -band absolute magnitudes (MK ) of about −23.5 < MK < −26 mag. Depending on the limiting MK , volume-limited surveys return different distributions: ATLAS3D (MK < −21.5 mag or D < 42 Mpc; Cappellari et al. 2011) contained 26% elliptical and 74% lenticular galaxies, while MASSIVE (MK < −23.5 mag or D < 108 Mpc; Ma et al. 2014) contained 68% and 32%, respectively. Because of ALMA's decl. limit and the abundance of targets in the ALMA archive with δ < 0°, we have only six galaxies in common with ATLAS3D (NGC 3245, NGC 4261, NGC 4429, NGC 4435, NGC 4697, and NGC 5838) and three in common with MASSIVE (NGC 997, NGC 3862, and NGC 5208). If we consider only ATLAS3D galaxies with MK ≲ −23.6 mag, the distribution of morphological types becomes identical to that of our sample. The galaxies in our sample have larger σc but lie somewhere between ATLAS3D (with MK ≲ −23.6 mag and median Re ∼ 3.4 kpc) and MASSIVE in terms of stellar luminosities (with a median MK ∼ −24.74 mag), with similar median Re. However, some of the most luminous (MK < −25.3 mag) and distant (D ≳ 100 Mpc) ETGs in our sample are very extended (Re > 10 kpc) and without analogs in the more local Universe. Restricting this comparison to ETGs in our sample that are within the ATLAS3D 42 Mpc distance limit, we find that our sample is moderately more compact (median Re ∼ 3.14 kpc). This selection bias follows a known trend of dynamical BH mass measurements being preferentially pursued in more compact galaxies relative to the distribution at a fixed luminosity, or in systems with larger projected rg (van den Bosch et al. 2015). As we determine in Section 4.3, over half of our sample have cored surface-brightness profiles, while the remainder exhibit steeper slopes; volume-limited ETG surveys show much greater preference for cuspy central slopes (Krajnović et al. 2013). Lastly, nearly every object in our sample is a member of some galaxy group, and five (Hydra A, NGC 3258, NGC 3268, NGC 3557, and NGC 6861) are referenced in the literature as either BGGs or BCGs (Garcia 1993; Zabludoff & Mulchaey 2000; Sato et al. 2012; Caso et al. 2013).

Figure 1. Galaxy properties for this sample compared to those from the ATLAS3D and MASSIVE surveys. Distances and absolute Ks -band magnitudes (left; following Ma et al. 2014) demonstrate our sample occupies an intermediate range of luminosities, while tending to have higher central velocity dispersions (σc ; upper right) but only slightly smaller median half-light radii (Re; lower right) when compared to a subsample of ATLAS3D targets with MK < −23.59 mag. The Re values for the ATLAS3D survey were derived from a combination of Third Reference Catalogue of Bright Galaxies (RC3) and Two Micron All Sky Survey determinations, normalized to agree on average with RC3 (Cappellari et al. 2011).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 1. Early-type Galaxy Sample

| Galaxy | RC3 | m − M | AGal,F160W | z | DL | DA | Scale | Re | σc | MK | LH | rg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Type | (mag) | (mag) | (Mpc) | (Mpc) | (kpc arcsec−1) | (kpc) | (km s−1) | (mag) | (1011 L☉) | (arcsec) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) |

| Hydra A | (R')SA0∧−: | 36.89 ± 0.15 | 0.021 | 0.055782 | 238.70 | 214.14 | 1.038 | 17.79 | 341.1 | −25.99 | 4.958 | 0.13 |

| NGC 612 | SA0∧+ pec | 35.46 ± 0.15 | 0.010 | 0.029430 | 123.60 | 116.63 | 0.565 | 5.79 | ⋯ | −25.86 | 3.591 | 0.22 |

| edge-on | ||||||||||||

| NGC 997 | E | 34.71 ± 0.15 | 0.071 | 0.021015 | 87.70 | 84.13 | 0.408 | 4.96 | ⋯ | −25.26 | 2.168 | 0.22 |

| NGC 1332 | S0∧−:(s) | 31.80 ± 0.18 (1) | 0.017 | 0.005180 | 22.91 | 22.67 | 0.110 | 2.87 | 294.6 | −24.74 | 1.369 | 0.57 |

| edge-on | ||||||||||||

| NGC 1387 | SAB0∧-(s) | 31.80 ± 0.09 (5) | 0.006 | 0.004079 | 19.32 | 19.16 | 0.093 | 1.40 | 167.3 | −23.94 | 0.593 | 0.42 |

| NGC 3245 | SA0∧0(r):? | 31.43 ± 0.20 (1) | 0.013 | 0.005854 | 20.89 | 20.65 | 0.100 | 2.87 | 207.0 | −23.70 | 0.658 | 0.33 |

| NGC 3258 | E1 | 32.53 ± 0.27 (1) | 0.041 | 0.009580 | 32.06 | 31.46 | 0.153 | 2.57 | 261.0 | −24.34 | 0.788 | 0.32 |

| NGC 3268 | E2 | 32.73 ± 0.25 (1) | 0.053 | 0.009280 | 34.83 | 34.20 | 0.166 | 5.99 | 228.6 | −24.54 | 1.342 | 0.34 |

| NGC 3271 | SB0∧0(r) | 33.73 ± 0.15 | 0.056 | 0.013393 | 55.60 | 54.14 | 0.262 | 4.59 | 246.8 | −25.54 | 2.765 | 0.40 |

| NGC 3557 | E3 | 33.30 ± 0.22 (1) | 0.052 | 0.009867 | 45.71 | 44.82 | 0.217 | 6.64 | 270.3 | −26.06 | 4.844 | 0.65 |

| NGC 3862 | E | 34.95 ± 0.15 | 0.012 | 0.023403 | 97.80 | 93.38 | 0.453 | 15.26 | 265.1 | −25.41 | 3.946 | 0.21 |

| NGC 4061 | E: | 35.21 ± 0.15 | 0.018 | 0.026302 | 110.20 | 104.62 | 0.507 | 10.48 | 477.2 | −25.32 | 3.116 | 0.18 |

| NGC 4261 | E2−3 | 32.34 ± 0.19 (2) | 0.009 | 0.003332 | 29.38 | 29.18 | 0.141 | 5.02 | 296.7 | −25.05 | 2.099 | 0.54 |

| NGC 4373a | SA0∧+: | 32.60 ± 0.52 | 0.043 | 0.008019 | 33.10 | 32.58 | 0.158 | 2.94 | 201.6 | −23.77 | 0.640 | 0.23 |

| edge-on | ||||||||||||

| NGC 4429 | SA0∧+(r) | 30.73 ± 0.15 | 0.017 | 0.003382 | 13.90 | 13.81 | 0.067 | 2.65 | 173.4 | −23.93 | 0.647 | 0.58 |

| NGC 4435 | SB0∧0(s) | 31.12 ± 0.05 (4) | 0.015 | 0.003399 | 16.75 | 16.64 | 0.081 | 1.38 | 155.0 | −23.75 | 0.420 | 0.41 |

| NGC 4697 | E6 | 30.35 ± 0.14 (1) | 0.015 | 0.005114 | 11.75 | 11.63 | 0.056 | 2.51 | 165.2 | −24.00 | 0.689 | 0.71 |

| NGC 4751 | SA0∧−: | 31.86 ± 0.16 | 0.062 | 0.005694 | 23.50 | 23.24 | 0.113 | 2.46 | 350.6 | −23.59 | 0.556 | 0.29 |

| NGC 4786 | cD pec | 34.26 ± 0.15 | 0.019 | 0.017115 | 71.20 | 68.82 | 0.334 | 8.49 | 284.7 | −25.51 | 3.743 | 0.30 |

| NGC 4797 | S0∧−: | 35.35 ± 0.15 | 0.006 | 0.028053 | 117.70 | 111.36 | 0.540 | 6.14 | 201.7 | −25.44 | 2.210 | 0.18 |

| NGC 5084 | S0 edge-on | 31.85 ± 0.15 | 0.060 | 0.005664 | 23.40 | 23.14 | 0.112 | 2.50 | 199.8 | −24.77 | 1.138 | 0.59 |

| NGC 5193 | E pec: | 33.35 ± 0.15 (2) | 0.029 | 0.010247 | 46.77 | 45.83 | 0.222 | 3.22 | 205.1 | −24.66 | 1.187 | 0.24 |

| NGC 5208 | S0 | 35.09 ± 0.15 | 0.018 | 0.024894 | 104.20 | 99.20 | 0.481 | 12.35 | ⋯ | −25.55 | 4.475 | 0.22 |

| NGC 5838 | SA0∧− | 31.75 ± 0.15 | 0.027 | 0.005420 | 22.40 | 22.16 | 0.107 | 1.74 | 273.6 | −24.13 | 0.667 | 0.41 |

| NGC 6861 | SA0∧−(s): | 32.24 ± 0.36 (1) | 0.028 | 0.010137 | 28.05 | 27.49 | 0.133 | 2.36 | 387.2 | −24.74 | 1.263 | 0.47 |

| NGC 6958 | cD | 33.03 ± 0.15 | 0.023 | 0.009750 | 40.30 | 39.53 | 0.192 | 2.98 | 185.2 | −24.59 | 1.246 | 0.30 |

Notes. Properties of the ETGs observed in these HST programs. Column (2) gives the galaxy morphology reported by de Vaucouleurs et al. (1991). Column (3) lists the adopted distance modulus, with preference for SBF measurements. SBF measurements were drawn from (1) Tonry et al. (2001), (2) Jensen et al. (2003), (3) Cantiello et al. (2005), (4) Mei et al. (2007), and (5) Blakeslee et al. (2009). The remainder were derived from a luminosity distance (DL ) that is itself estimated using corrected redshifts and a standard cosmology as described in Section 1. Columns (4) and (5) report Galactic extinction in the Wide Field Camera 3/F160W band and optical redshifts from the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED) after correcting for the Virgo + Great Attractor + Shapley inflow model (Mould et al. 2000). Columns (6) and (7) give DL and angular size distance (DA ) corresponding to the adopted z values and cosmology computed using the Wright (2006) cosmological calculator, with the corresponding physical scale given in column (8). Column (9) gives an H-band effective radius Re estimate using the half-light radius from the corresponding multi-Gaussian expansion (MGE) described in Section 5. Column (10) gives the measured central stellar velocity dispersion from the HyperLEDA database (Paturel et al. 2003); the apparent total K-band magnitudes, also from HyperLEDA, are combined with the adopted DL to estimate MK for each galaxy in column (11). Column (12) gives the total H-band luminosity estimated from MGE models. Lastly, column (13) gives the estimated rg value from the MBH–LK scaling relation (Kormendy & Ho 2013).

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

For 12 of these galaxies, we adopted luminosity distances (DL ) from surface brightness fluctuation (SBF) distance modulus measurements (Tonry et al. 2001; Jensen et al. 2003; Cantiello et al. 2005; Mei et al. 2007; Blakeslee et al. 2009). For the remaining 14 galaxies lacking SBF-derived m − M values, we estimated DL from Hubble flow velocities using the Virgo + Great Attractor + Shapley supercluster inflow model (Mould et al. 2000) and the Wright (2006) cosmological calculator, assuming the corrected redshift reported in the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED) is entirely cosmological in origin. 12 The median uncertainty in SBF-derived m − M corresponds to ∼12% uncertainty in DL , while Hubble-flow-derived distance moduli give only lower-bound ∼7% uncertainties from redshift errors alone. The uncertainties in the physical scale are calculated to be ∼18% from the median distance and redshift errors.

We note that nine of the targets in our sample already have published BH mass measurements or estimates (Barth et al. 2016a, 2016b; Davis et al. 2017, 2018; Boizelle et al. 2019, 2021; Ruffa et al. 2019b, 2023; Kabasares et al. 2022; Thater et al. 2022). For two of these ETGs (NGC 3258 and NGC 4261), the respective HST data have already been utilized in gas-dynamical modeling (Boizelle et al. 2019, 2021). For uniformity, however, we analyze them again using the approach outlined in Sections 3 and 5. In many cases, the stellar luminosity models constructed here will still be useful in any reanalysis of the ALMA CO data, or in more comprehensive explorations of CND dust attenuation.

3. Optical/Near-IR Data

Our sample of 26 ETGs had inconsistent broadband imaging in the optical/near-IR regimes, although all had Spitzer Infrared Array Camera (IRAC; Fazio et al. 2004) channel 1 or 2 imaging that probes far out into the stellar halo. None had high-resolution near-IR data to mitigate the impact of dust attenuation while also covering a sufficiently wide FOV, which is needed to construct stellar luminosity models, and only half had HST imaging in the F814W filter (or similar; see Table 2). In this section, we detail efforts to calibrate, mosaic, and align HST data across multiple filters. We also discuss near-IR sky subtraction with the help of larger-scale Spitzer data.

Table 2. New and Archival HST Observations

| Galaxy | This Paper1 | Other Programs | GO ID | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | WFC3/IR | WFC3/UVIS | WFPC2 | ACS | WFC3/UVIS | |

| Hydra A | F110W, F160W | F475W | ⋯ | F814W | ⋯ | 12220 (PI: Mittal) |

| NGC 612 | F110W, F160W | F475W | ⋯ | F814W | ⋯ | 15444 (PI: Barth) |

| NGC 997 | F110W, F160W | F475W, F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| NGC 1332 | F110W, F160W | F438W | F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 5999 (PI: Phillips) |

| NGC 1387 | F110W, F160W | ⋯ | F606W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 5446 (PI: Illingworth) |

| ⋯ | F475W, F850LP | ⋯ | 10217 (PI: Jordan) | |||

| NGC 3245 | F110W, F160W | F475W | F547M | ⋯ | ⋯ | 6837 (PI: Ho) |

| NGC 3258 | F110W, F160W | ⋯ | ⋯ | F435W, F814W | ⋯ | 9427 (PI: Harris) |

| NGC 3268 | F110W, F160W | F555W | ⋯ | F435W, F814W | ⋯ | 9427 (PI: Harris) |

| NGC 3271 | F110W, F160W | F475W, F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| NGC 3557 | F110W, F160W | F438W | F555W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 6587 (PI: Richstone) |

| NGC 3862 | F110W, F160W | ⋯ | F547M, F791W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 5927 (PI: Ford) |

| F702W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 9069 (PI: Biretta) | |||

| ⋯ | ⋯ | F225W, F475W, F814W | 14159 (PI: Meyer) | |||

| NGC 4061 | F110W, F160W | F475W | F555W, F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 9106 (PI: Richstone) |

| NGC 4261 | F110W, F160W | ⋯ | F547M, F675W, F791W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 5124 (PI: Ford) |

| F702W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 5476 (PI: Sparks) | |||

| F450W, F606W, F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 11339 (PI: Zezas) | |||

| NGC 4373a | F110W, F160W | F475W, F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| NGC 4429 | F110W, F160W | F475W, F814W | F606W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 5446 (PI: Illingworth) |

| NGC 4435 | F110W, F160W | ⋯ | F450W, F675W, F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 6791 (PI: Kenney) |

| ⋯ | F475W, F850LP | ⋯ | 9401 (PI: Cote) | |||

| NGC 4697 | F110W, F160W | F555W | ⋯ | F475W, F850LP | ⋯ | 10003 (PI: Sarazin) |

| ⋯ | ⋯ | F225W, F336W | 11583 (PI: Bregman) | |||

| NGC 4751 | F110W, F160W | F475W, F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| NGC 4786 | F110W, F160W | F438W | F555W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 6587 (PI: Richstone) |

| NGC 4797 | F110W, F160W | F475W, F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| NGC 5084 | F110W, F160W | F475W | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| NGC 5193 | F110W, F160W | F475W | F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 5910 (PI: Lauer) |

| NGC 5208 | F110W, F160W | F475W, F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| NGC 5838 | F110W, F160W | F555W | F450W, F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 7450 (PI: Peletier) |

| NGC 6861 | F110W, F160W | F438W | F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 5999 (PI: Phillips) |

| NGC 6958 | F110W, F160W | F475W | F547M, F814W | ⋯ | ⋯ | 8686 (PI: Goudfrooij) |

Notes. Optical and near-IR medium- and broadband-filter HST observations that provide good coverage and depth. New WFC3/IR and UVIS observations (GO IDs1: 14920, 15226, and 15909; PI: Boizelle)

1 supplement archival data sets that were obtained using the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2), Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS), or WFC3/UVIS instruments, ensuring sufficient coverage and sampling for dust-attenuation modeling. The typical H-band FOV is 3 6 × 3

6 × 3 6 with exposure times ranging from 250 to 400 s. The J-band images are typically subarrays with a FOV of ∼1' × 1' and exposure times ranging from 100 to 250 s. The optical data range of coverage typically fell between the H- and J-band ranges, with an average FOV of 2

6 with exposure times ranging from 250 to 400 s. The J-band images are typically subarrays with a FOV of ∼1' × 1' and exposure times ranging from 100 to 250 s. The optical data range of coverage typically fell between the H- and J-band ranges, with an average FOV of 2 5 × 2

5 × 2 5 and exposure times ranging from 150 to 400 s.

5 and exposure times ranging from 150 to 400 s.Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

3.1. HST Imaging

We observed each ETG in a single HST orbit through programs GO-14920, GO-15226, or GO-15909 (Cycles 24, 25, and 27; PI: Boizelle) using the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3; Dressel 2022) in the IR channel with a focus on F160W data. For just over half of our targets, we obtained additional WFC3/UVIS imaging to provide either the first or supplemental optical HST imaging, since broad wavelength coverage is crucial in constraining dust attenuation (as a Galactic reddening law has Aλ decreasing by a factor of ∼8 from the B to H bands). All these HST data can be found in the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST) doi:10.17909/98s2-be33 and on Zenodo doi:10.5281/zenodo.11122962. In Table 2, we list these new WFC3 data together with the archival Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2; McMaster & Biretta 2008), Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS; Ryon 2022), and WFC3 observations that were selected for this project to span the desired wavelength range.

3.1.1. New WFC3 Data

In the IR channel, we obtained both F110W and F160W (hereafter J and H) imaging for all targets, primarily to construct a near-IR mosaic that adequately samples the CND while also probing well into the stellar halo. We employed a four-point dither pattern for H-band observations, adopting the WFC3-IR-DITHER-BOX-MIN pattern to more optimally sample the H-band point-spread function (PSF) for more compact galaxies. For more extended targets, we used a large square dither pattern with offsets of up to 75'' and a total coverage of up to 3 6 × 3

6 × 3 6. In all cases, we placed the central bright region of each galaxy within the overlap of the four pointings. In most cases, these WFC3/IR mosaics cover out to a few × Re, with a median projected Re ∼ 20'' and a maximum of ∼40''. Individual H-band exposure times ranged from 250 to 400 s, using various SPARS or STEP sampling sequences to avoid time loss due to buffer dumps. Each MULTIACCUM image had NSTEP = 9 or higher to enable good up-the-ramp calibration and cosmic-ray rejection. Combined exposure times in the overlap regions deliver background-limited sensitivity for this filter, and we estimate a typical 1σ surface-brightness depth of ∼25.9 mag arcsec−2 in a 1'' × 1'' region measured at the edges of this dither pattern.

6. In all cases, we placed the central bright region of each galaxy within the overlap of the four pointings. In most cases, these WFC3/IR mosaics cover out to a few × Re, with a median projected Re ∼ 20'' and a maximum of ∼40''. Individual H-band exposure times ranged from 250 to 400 s, using various SPARS or STEP sampling sequences to avoid time loss due to buffer dumps. Each MULTIACCUM image had NSTEP = 9 or higher to enable good up-the-ramp calibration and cosmic-ray rejection. Combined exposure times in the overlap regions deliver background-limited sensitivity for this filter, and we estimate a typical 1σ surface-brightness depth of ∼25.9 mag arcsec−2 in a 1'' × 1'' region measured at the edges of this dither pattern.

For wavelengths bluer than the H band, observations were centered on the CND, with the observing setup adapted to avoid costly buffer dumps and fit each target in a single orbit. We generally obtained the J-band data using the IRSUB512-FIX subarray aperture, employing the 2-point WFC3-IR-DITHER-LINE pattern to better sample the PSF, with a final FOV of about 60'' × 60''. For nearly 80% of our sample, this J-band FOV covers out to at least one (projected) Re from the nucleus. In a few cases, the available optical data and orbit constraints allowed for full-aperture J-band imaging. Sampling sequences for the J-band observations were similar to those employed in acquiring the H-band data. Individual exposure times generally ranged between 100 and 250 s, with combined exposure time reaching (or exceeding) the threshold for background-limited sensitivity. Two cases with extended stellar light distributions (NGC 3862 and NGC 4261) host AGNs that are more prominent in the optical, and we obtained additional J- and H-band imaging of these galaxies to better characterize the near-IR point sources. These data employed an IRSUB256-FIX aperture with an ideal four-point dither pattern and the SPARS5/NSAMP = 15 combination for rapid temporal sampling, with a total exposure time for an individual pointing of 33 s.

For over 80% of our sample, the existing HST optical data were not sufficient for our eventual goal of constraining dust attenuation arising from the CNDs. We obtained additional WFC3/UVIS data using the F438W or F475W filter (B band) and/or the F814W filter (I band) to ensure broad wavelength coverage. In a few cases, orbit scheduling also allowed for F555W imaging for more complete wavelength sampling. To allow all data for a given object to be scheduled in a single orbit, we chose either the UVIS1-2K2A-SUB or UVIS2-M1K1C-SUB apertures. Total exposure lengths for individual frames ranged from 150 to 400 s depending on the time available. To limit the impact of cosmic rays, observations in a single filter were split into either two or three frames and dithered using the corresponding WFC3-UVIS-DITHER-LINE pattern.

3.1.2. Archival Data

We retrieved optical (and occasionally UV) ACS, WFPC2, and WFC3 images of our target galaxies from MAST. 13 When there were duplicates in a specific wavelength regime, preference was given to data taken with later-generation detectors, sequences that gave better spatial coverage of the dusty CND, and better angular resolution. Additional criteria included good image quality (e.g., low incidence of cosmic rays overlapping with the CND) and an unsaturated nucleus. Narrowband data were not included in the final analysis due to the likelihood of emission-line contamination (e.g., Walsh et al. 2008). As mentioned earlier, NICMOS data were not included due to calibration issues toward that instrument's edges and its limited FOV.

3.1.3. Calibration and Analysis

After processing these new HST data through the CALWF3 pipeline (Dressel 2022), we created final H-band mosaics and B, I, and J subarray products using AstroDrizzle (Gonzaga et al. 2012). All images were drizzled to the same pixel scale of 0 08 pixel−1 to facilitate the exploration of dust extinction across each CND. For the dithered WFC3/IR data, we adopted a pixel fraction of 0.75 to optimize the PSF sampling and pixel noise. Since the WFC3/UVIS data had smaller detector pixel sizes but less ideal dithering, we used the same pixel fraction. In general, these WFC3 data obtained in a single orbit remain well aligned after drizzling. In Figure 2, we show examples of our H-band mosaics and the HST footprint overlaid on larger-scale near-IR imaging.

08 pixel−1 to facilitate the exploration of dust extinction across each CND. For the dithered WFC3/IR data, we adopted a pixel fraction of 0.75 to optimize the PSF sampling and pixel noise. Since the WFC3/UVIS data had smaller detector pixel sizes but less ideal dithering, we used the same pixel fraction. In general, these WFC3 data obtained in a single orbit remain well aligned after drizzling. In Figure 2, we show examples of our H-band mosaics and the HST footprint overlaid on larger-scale near-IR imaging.

Figure 2. HST WFC3/F160W (H-band) drizzled mosaics for three targets overlaid on Spitzer IRAC1 (3.6 μm) supermosaics that were scaled to match the H-band data at the edge of the HST footprint. These targets highlight the diversity of stellar halo extents and the challenges in accurately determining the H-band sky background for most of the sample. Images are displayed using a logarithmic intensity scale.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imagePreliminary mosaicing of the archival HST data did not align well with the new WFC3 data, so we first aligned the pipeline-calibrated files to the H-band mosaic using TweakReg (Gonzaga et al. 2012). We then combined the single-filter data in AstroDrizzle using the same pixel scale. The accuracy of dust-attenuation modeling is very sensitive to the relative (subpixel) alignment of data across all filters. Slight offsets between different filters were still present, so to further improve the alignment of the HST data for each target, we calculated a luminosity-weighted centroid using a series of stellar isophotes that were measured beyond the dusty features of the CND. Afterwards, we corrected for the offsets of the shorter-wavelength data relative to the H-band mosaic. Finally, we confirmed the accuracy of these subpixel offsets (or introduced additional fine-tuning) by inspecting the resulting color maps. In Figure 3, we show an example of the alignment of these multiwavelength images for a single target.

Figure 3. Aligned HST images (left) show the NGC 4435 nucleus and CND across five different optical/near-IR filters and two detectors, displayed using an inverted grayscale. The scale bar corresponds to 100 pc. Surface-brightness measurements extracted along the major axis (right; without any dust masking and scaled together at R = 3 5) show the >2× change in attenuation, and the best-fit stellar luminosity model for the H-band mosaic (dust-masked; see Section 5) fits the data well. At the disk outskirts between 2

5) show the >2× change in attenuation, and the best-fit stellar luminosity model for the H-band mosaic (dust-masked; see Section 5) fits the data well. At the disk outskirts between 2 5 < R < 3

5 < R < 3 5, the diffuse dust primarily impacts the optical filters, while the highest-column-density gas lies between 1

5, the diffuse dust primarily impacts the optical filters, while the highest-column-density gas lies between 1 5 < R < 2

5 < R < 2 5. The dust radius Rdust,H

from Table 3 identifies the extent of the near-IR-thick disk.

5. The dust radius Rdust,H

from Table 3 identifies the extent of the near-IR-thick disk.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageRecovering intrinsic stellar luminosities necessitates a prescription for the PSF in a given filter. Following standard practice, we created model H-band PSFs for each target by dithering and drizzling copies of the Tiny Tim (Krist & Hook 2004) F160W response, as we did for the HST data. This dithering and drizzling process returns PSFs with somewhat narrower FWHMs (average FWHM ∼ 0 19) than are observed for foreground stars in the H-band mosaics (generally ∼0

19) than are observed for foreground stars in the H-band mosaics (generally ∼0 22–0

22–0 24). An alternative approach is to employ an empirical PSF using either stars in each field or an average point-source response near a particular detector location. The H-band mosaics of our sample do not contain many suitable PSF stars, and galaxy light often contaminates the PSF wings. Therefore, we employed the composite WFC3/F160W PSF provided by STScI (Anderson 2016), again dithering and drizzling copies of this frame in the same manner as done for the Tiny Tim files. While the empirical PSF only extends out to R ∼ 1'', it produces slightly better agreement (FWHM ∼ 0

24). An alternative approach is to employ an empirical PSF using either stars in each field or an average point-source response near a particular detector location. The H-band mosaics of our sample do not contain many suitable PSF stars, and galaxy light often contaminates the PSF wings. Therefore, we employed the composite WFC3/F160W PSF provided by STScI (Anderson 2016), again dithering and drizzling copies of this frame in the same manner as done for the Tiny Tim files. While the empirical PSF only extends out to R ∼ 1'', it produces slightly better agreement (FWHM ∼ 0 20–0

20–0 21) with those measured in the H-band mosaics. None of our targets have overly dominant H-band point sources, so subsequent stellar luminosity fits are not affected by the limited PSF response range. In Section 5, we compare stellar luminosity models constructed using both a theoretical and an empirical PSF, while for the remainder of this paper we adopt results that employed the Tiny Tim PSF.

21) with those measured in the H-band mosaics. None of our targets have overly dominant H-band point sources, so subsequent stellar luminosity fits are not affected by the limited PSF response range. In Section 5, we compare stellar luminosity models constructed using both a theoretical and an empirical PSF, while for the remainder of this paper we adopt results that employed the Tiny Tim PSF.

3.2. Spitzer Imaging and Sky Subtraction

Based on an initial analysis, nine galaxies were sufficiently compact (or distant) to allow for accurate H-band sky removal using the edges of the corresponding WFC3 mosaics. For the remaining 17 galaxies (see Table 3), H-band stellar light contributions near the edges of the HST footprint were close to the expected background level (primarily zodiacal in origin; Pirzkal 2014), as estimated using the WFC3/IR Exposure Time Calculator (ETC) for the corresponding solar angles. 14 Such a high level of stellar light that persists out to a projected distance of precludes accurate sky subtraction using the H-band data alone. Following the method outlined by Boizelle et al. (2019), we determined those sky values with the aid of larger-scale Spitzer IRAC channel 1 (3.6 μm) supermosaics from the Spitzer Heritage Archive, 15 with the data available at the Infrared Science Archive doi:10.26131/IRSA361. After masking galaxies, foreground stars, and noisy regions in these Spitzer data, we extracted H-band and IRAC1 surface-brightness profiles in the same direction toward the corner of the HST mosaic. Using overlapping measurements between R ∼ 20''–70'' (median of about 1−3 Re), we simultaneously determined both the average H − IRAC1 color and the H-band sky background. This radius range avoids PSF blurring effects, and the near-IR color gradients tend to be mild (e.g., Tamura & Ohta 2003; Iodice et al. 2019) but increasingly blue with radius. The best-fit H-band sky values (μsky,H ∼ 20–21 mag arcsec−2) mostly agree with ETC values, and the median H − IRAC1 ∼ 2.20 mag at these radii with a standard deviation of ∼0.16 mag is consistent with the color of an evolved, metal-rich single-burst stellar population (with total metallicity [M/H] = 0.22 with an age of 10 Gyr; Vazdekis et al. 2012, 2016).

Table 3. CND Properties, Isophotal Analysis, and Spitzer Scaling Results

| CND Properties | Stellar Isophotal Results | Near-IR Colors | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galaxy | Rdust,H | (b, a)dust,H | PAdust,H | ΔPA⋆ | Δε⋆ | Median | Min,max | IC | H − IRAC1 | ∇J−H | ||

| Name | (kpc) | (arcsec) | (deg) | (deg) | (deg) | a4/a | a4/a | (mag) | (mag) | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) |

| Hydra A | 2.03 | 0.27, 1.96 | −75.3 | −36.0 | 41.2 | 0.126 | 0.304 | −0.006 | −0.101, 0.003 | x0b | ⋯ | −0.024 |

| NGC 612 | 10.8 | 2.90, 19.1 | −11.0 | −15.4 | 46.8 | 0.265 | 0.198 | 0.014 | −0.023, 0.046 | xd? | 2.26 | −0.027 |

| NGC 997 | 2.32 | 4.69, 5.70 | 32.6 | 29.7 | 11.0 | 0.121 | 0.034 | −0.006 | −0.043, −0.002 | x0b | ⋯ | −0.103 |

| NGC 1332 | 0.24 | 0.17, 2.17 | 114.9 | 116.7 | 3.4 | 0.321 | 0.445 | −0.007 | −0.014, 0.005 | x0b | 2.12 | −0.031 |

| NGC 1387 | 0.88 | 8.35, 9.43 | 52.1 | 108.7 | 54.5 | 0.146 | 0.296 | −0.001 | −0.015, 0.006 | x0 | 2.22 | −0.024 |

| NGC 3245 | 0.16 | 0.59, 1.60 | −6.9 | −3.4 | 19.7 | 0.367 | 0.367 | 0.001 | −0.091, 0.024 | xd0? | 2.65 | −0.054 |

| NGC 3258 | 0.15 | 0.58, 0.99 | 75.0 | 76.3 | 21.3 | 0.176 | 0.188 | −0.001 | −0.009, 0.031 | x0d | 2.66 | −0.071 |

| NGC 3268 | 0.40 | 1.27, 2.40 | −108.6 | −112.1 | 7.4 | 0.196 | 0.097 | 0.001 | −0.002, 0.007 | x0 | 2.20 | −0.044 |

| NGC 3271 | 0.46 | 1.04, 1.74 | −86.1 | −66.9 | 33.7 | 0.322 | 0.280 | −0.003 | −0.035, 0.043 | xd0db | ⋯ | −0.058 |

| NGC 3557 | 0.22 | 0.62, 0.99 | 36.2 | 33.4 | 7.7 | 0.245 | 0.122 | 0.002 | −0.006, 0.011 | x0 | 2.20 | −0.025 |

| NGC 3862 | 0.38 | 0.80, 0.84 | −9.0 | −16.0 | 62.7 | 0.022 | 0.344 | 0.002 | −0.019, 0.015 | x0d0b | 2.27 | −0.046 |

| NGC 4061 | 0.92 | 0.93, 1.81 | −6.2 | −5.6 | 28.1 | 0.184 | 0.084 | −0.006 | −0.076, 0.027 | x0b | ⋯ | −0.063 |

| NGC 4261 | 0.13 | 0.51, 0.89 | −16.4 | −22.3 | 11.1 | 0.220 | 0.137 | −0.002 | −0.014, 0.004 | x0 | 2.20 | −0.024 |

| NGC 4373a | 0.95 | 2.17, 6.00 | −26.0 | −32.4 | 9.7 | 0.428 | 0.404 | 0.003 | −0.010, 0.030 | x0d0 | ⋯ | −0.123 |

| NGC 4429 | 0.90 | 5.62, 13.5 | 90.3 | 94.4 | 11.5 | 0.439 | 0.248 | 0.004 | −0.013, 0.043 | x0db0 | 2.15 | −0.021 |

| NGC 4435 | 0.25 | 0.86, 3.07 | 13.8 | 6.3 | 28.8 | 0.362 | 0.273 | 0.002 | −0.018, 0.054 | x0bd0d | 2.13 | −0.042 |

| NGC 4697 | 0.20 | 0.95, 3.48 | 65.3 | 66.0 | 2.3 | 0.436 | 0.142 | −0.003 | −0.010, 0.003 | x0 | 2.13 | −0.034 |

| NGC 4751 | 1.54 | 3.22, 13.7 | −5.1 | −4.9 | 5.2 | 0.587 | 0.102 | −0.003 | −0.031, 0.008 | x0b | ⋯ | −0.157 |

| NGC 4786 | 0.19 | 0.32, 0.57 | −13.1 | −17.0 | 13.1 | 0.224 | 0.105 | 0.002 | −0.011, 0.033 | x0d | 2.20 | −0.025 |

| NGC 4797 | 5.72 | 4.64, 10.6 | 22.8 | 31.0 | 17.8 | 0.251 | 0.219 | 0.001 | −0.013, 0.024 | x0d | ⋯ | −0.069 |

| NGC 5084 | 0.13 | 0.44, 1.18 | −2.0 | 82.8 | 5.7 | 0.388 | 0.449 | −0.002 | −0.016, 0.006 | x0b? | 2.13 | −0.023 |

| NGC 5193 | 0.21 | 0.60, 0.96 | 64.7 | 70.8 | 46.1 | 0.209 | 0.196 | 0.005 | −0.031, 0.047 | x0d? | ⋯ | −0.036 |

| NGC 5208 | 8.70 | 3.42, 18.1 | −17.7 | −17.1 | 6.2 | 0.611 | 0.050 | −0.006 | −0.008, 0.036 | x0? | ⋯ | −0.083 |

| NGC 5838 | 0.45 | 1.70, 4.15 | 36.8 | 47.4 | 11.9 | 0.243 | 0.464 | −0.004 | −0.023, 0.007 | x0b0 | 2.18 | −0.080 |

| NGC 6861 | 1.01 | 1.92, 7.60 | −37.9 | −38.0 | 25.7 | 0.458 | 0.224 | 0.002 | −0.002, 0.038 | x0d | 2.19 | −0.078 |

| NGC 6958 | 0.25 | 1.15, 1.29 | 105.5 | 109.7 | 43.7 | 0.125 | 0.225 | −0.001 | −0.024, 0.050 | x0bd? | 2.25 | −0.059 |

Notes. General CND properties together with near-IR stellar light behavior. Columns (2), (3), and (4) report the (physical) outer dust-disk radius, the (projected) minor and major axes, and the corresponding position angle, respectively, estimated primarily from the H-band data but with some input from bluer data. Columns (5) and (7) give the average stellar photometric PA and ellipticity, respectively, generally averaged from Rdust,H to Re in most cases. Columns (6) and (8) give the range of PA⋆ and ε⋆ values from stellar isophotal fitting just beyond Rdust,H to near the edge of the H-band mosaic. Additional details are found in Section 4.2. Columns (9), (10), and (11) report the median and range of a4/a parameters over this same range, and the isophotal codes (ICs; Rest et al. 2001) over the H-band surface-brightness extent from smallest to largest radii; x, d, b, 0, and ? represent regions undetermined due to dust, disky, boxy, intermediate, and uncertain/inconsistent a4/a regions. To this table are added the best-fitting H –IRAC1 color terms in column (12) to scale together these surface-brightness profiles. Column (13) reports the logarithmic J − H color gradient, measured from Rdust,H to Re in most cases.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

Finally, we removed the sky background from the smaller-FOV J-band data. Except for a few cases where the ETG was sufficiently compact, we estimated J-band sky values by scaling the measured H-band levels by the ratio of J/H zodiacal light from the ETC estimates. Slight adjustments were made to ensure smooth color gradients at the largest radii probed by the WFC3/IR (sub)array mosaics. We note that any uncertainty in the near-IR sky subtraction does not affect the stellar luminosity models described in Section 5. Even if we change the H-band sky level by a factor of ∼2, the resulting circular velocity curves change by at most a few kilometers per second, and overwhelmingly in the galaxy outskirts.

4. Stellar Surface-brightness Behavior

After WFC3/IR and archival data alignment and sky subtraction, we constructed color maps and extracted radial profiles to explore the CND dust and stellar behavior across the WFC3/IR FOV. Examples of central stellar surface-brightness profiles in the available HST filters are shown in Figure 3. To isolate the galaxy light, we masked out all other galaxies, foreground stars and diffraction spikes, detector artifacts, and pixels affected by cosmic rays.

4.1. Near-IR Colors

HST near-IR color maps shown in Figure 4 are expected to isolate the optically thick dust distribution. As is shown in Figure 3, near-IR colors are not always sensitive to optically thin and occasionally filamentary features, which are not always detected in ALMA CO imaging (see also Boizelle et al. 2019). From each J − H map, we constructed an additional mask of the dust (see Figure 5) that nearly always contains the entire near side of the disk based on a color cutoff of J − H ≳ 0.88 mag (or an intrinsic color excess Δ(J − H) ≡ (J − H) − (J − H)⋆ ≳ 0.08 mag after subtracting off the stellar (J − H)⋆ that is evaluated just beyond the CND). From these J − H maps, we visually measured the semimajor and minor axes adust,H and bdust,H of the optically thick CND as well as the major-axis position angle PAdust,H (see Table 3). In most cases, the (physical) disk radius Rdust,H is a small fraction of Re. In fact, in only five cases (NGC 612, NGC 1387, NGC 4751, NGC 4797, and NGC 5208) is Rdust,H > Re/2. We note that Rdust,H is often 10%−20% smaller than Rdust measured in the B band, but we retain the H-band value as it better traces high-column-density material.

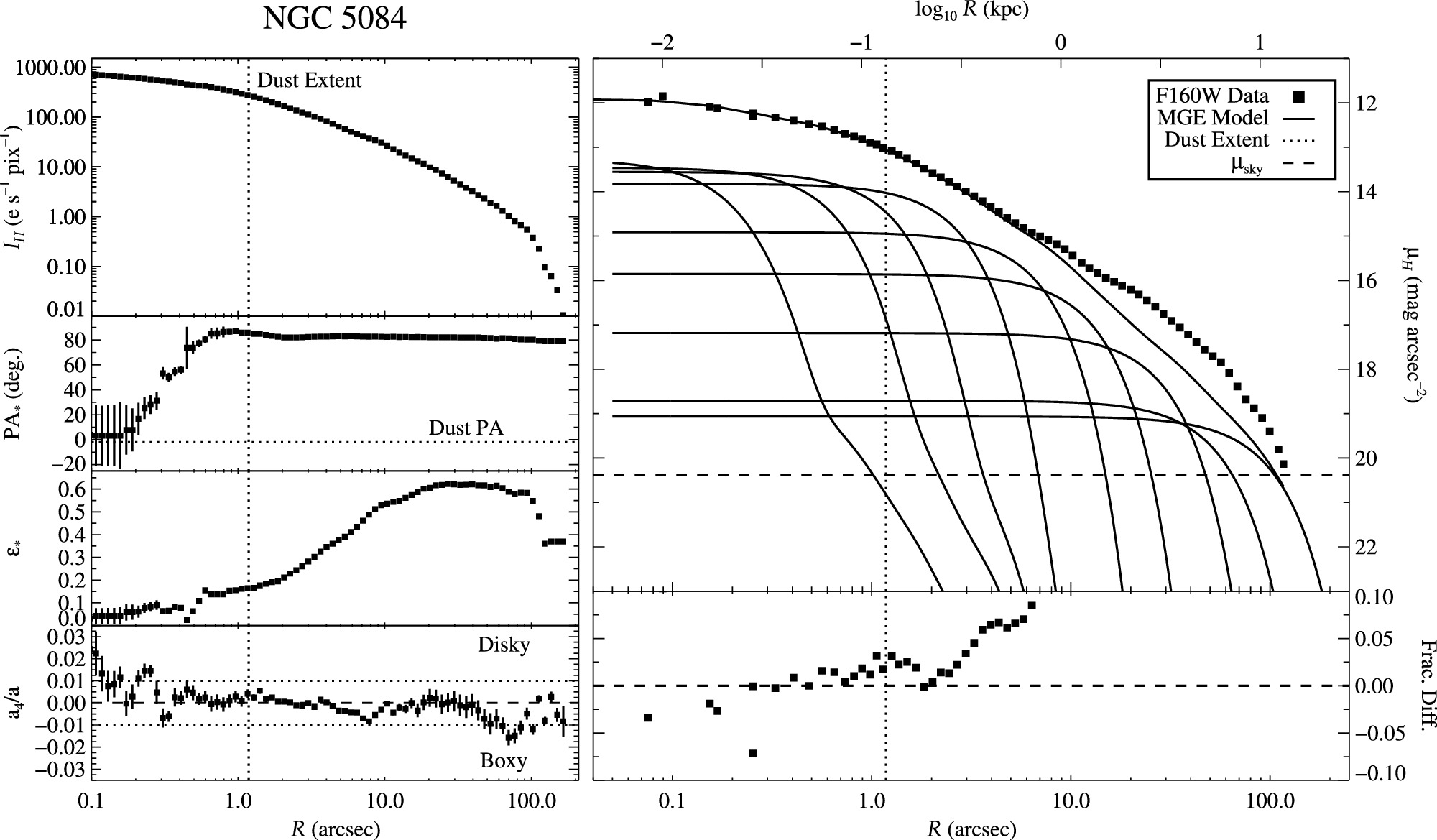

Figure 4. Central portions of J − H color maps, showing both the CNDs and their environs. The near side of each disk obscures a greater fraction of the stellar distribution, resulting in redder colors. While these CNDs were selected based on their regular dust morphology, filamentary dust features (especially in NGC 5084) or warped-disk structures (especially in NGC 612 and NGC 4797) are also detected. J − H colors (in mag) are mapped according to each color bar.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 5. Central portions of the H-band drizzled mosaics, with shaded regions showing the most dust-obscured portions of each CND based on high J − H colors (see Figure 4) that were masked during the MGE fit (overplotted in red). The CNDs of NGC 1387 and NGC 3862 were left unmasked due to either only marginal evidence for dust attenuation or a more face-on orientation that would require more complete masking of the inner ∼1''. Contours are placed at logarithmic intensity intervals.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 6 shows J − H and Δ(J − H) color profiles extracted along the stellar major axes, with Δ(J − H) reaching typical 0.06−0.10 mag reddening along the major axis at ∼(0.4–0.9)Rdust,H . Adopting a standard Galactic extinction law (RV = 3.1) and assuming that the CND lies in the midplane of each galaxy, the typical major-axis Δ(J − H) values above correspond to intrinsic AV ∼ 1.5–2.5 mag (for details, see Equations (1) and (2) from Boizelle et al. 2019). In some cases, the observed Δ(J − H) reaches the ∼0.15 mag turnover point corresponding to AV ∼ 5 mag (see Figure 3 of Boizelle et al. 2019), suggesting the innermost regions of certain CNDs become optically thick even in the H band. Along the major axis, the rough Δ(J − H) ≳ 0.08 mag masking criterion corresponds to AH ≳ 0.35 mag, or a drop of background stellar intensity of ∼25%.

Figure 6. Radial near-IR color and isophotal behavior of the ETG sample. Left: J − H color (above) and Δ(J − H) reddening (below) relative to stellar color just outside the CND plotted vs. radius normalized to the CND radius. The median stellar J − H color and its 1σ scatter just beyond Rdust,H are noted in the upper left panel. Center and right: position angle (PA⋆ − PA⋆,e; above) and ellipticity (ε⋆ − ε⋆,e; below) plotted vs. radius after removing the values PA⋆,e and ε⋆,e measured at the half-light radius Re, normalized to Re, for lenticular (center) and elliptical (right) galaxies, respectively. The position angle and ellipticity values are plotted starting just beyond the dust-disk extent (i.e., for all R ≥ Rdust,H ). The only exception is NGC 612 (plotted in orange), for which Rdust,H > Re. Galaxies labeled and highlighted in red are also contained in the MASSIVE survey, some of which are clear outliers in PA⋆ − PA⋆,e.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageBeyond the CND, the stellar J − H colors along the major axis show a gradual blueward trend with increasing radius. These (linear in ) trends are consistent with inside-out growth for (mostly) relaxed ETGs, with the bluer colors expected to arise from significant dry merger(s) (e.g., Saracco et al. 2012; Kim & Im 2013). To better compare these gradients to previous work (e.g., La Barbera et al. 2010), we adopt a logarithmic color gradient formalism:

where here Δ(J − H) refers to the difference in J − H color over a large radial range. Inner and outer R were set to slightly beyond Rdust,H (to avoid residual dust contamination) and 2 Re, respectively, in all cases except NGC 612, where we set the outer R = 3.5 Re because of the large Rdust,H ≈ 2 Re. The median ∇J−H ∼ −0.045 mag and fairly tight standard deviation of 0.034 mag are consistent with established near-IR color gradients of local ETGs (e.g., Aaronson 1977; La Barbera et al. 2010) and do not suggest steeper gradients for ETGs with dust features (see Kim & Im 2013). Our selection criteria avoided both lower-mass ETGs and those with more diffuse dust, which may explain the relatively tight ∇J−H distribution.

In general, these CNDs are expected to be relatively thin and flat, and so the (outer) disk kinematic angle i should satisfy (e.g., Barth et al. 2016a; Davis et al. 2017). We note that the observed axis ratio will tend to be more round than the intrinsic one due to beam smearing, especially for the smallest (projected) adust,H . As a result, the inferred i may be systemically smaller than the true value. Estimating i by kinemetric analysis of the observed CO velocity maps (Krajnović et al. 2006) is similarly fraught, as beam smearing tends to circularize the apparent kinematics except in cases where the outer CO extent RCO is much larger than the synthesized beam and the disk is not viewed too edge-on (e.g., Boizelle et al. 2017). This picture is further complicated by both photometric and kinematic evidence for disk warping. Color maps can identify some disk-warping signatures (e.g., NGC 612, NGC 3268, and NGC 4797 in Figure 4), although they cannot easily detect twists of Δi ≲ 10° or those within the inner couple of resolution elements. The prevalence and degree of disk warping has not yet been explored for a large sample of well-resolved CNDs. For four of our ETGs, however, Boizelle et al. (2017) find a shift in CO velocity line-of-nodes position angle (PA) of ΔPA ∼ 5°–10° across the entire CNDs. Boizelle et al. (2019) find a central Δi ∼ 20° for NGC 3258 from gas-dynamical modeling, although for most of the disk area Δi is low and i is consistent with the (b/a)dust,H estimate to within about 5°.

For the CNDs in our sample, we find a median i ∼ 65° estimated from (b/a)dust,H , with individual values ranging from 18° to 86°. The apparent preference for higher i in this sample likely stems from the greater ease of identifying more inclined disks in optical/near-IR imaging. Highly inclined disks do allow for more straightforward dust masking that removes fewer overall pixels and gives an essentially unobscured view along the minor axis. Despite the benefits when constructing stellar luminosity models, however, disks with i ≳ 75° are susceptible to substantial modeling degeneracies (e.g., Barth et al. 2016a, 2016b). Similar difficulties arise for nearly face-on orientations (i ≲ 15°; Smith et al. 2019). As a result, more intermediate i are preferred for the gas-dynamical approach.

4.2. Isophotal Analysis

To better compare to the stellar behavior of other ETGs and to quantify the discrepancies between dust disk and stellar alignment, we analyzed the H-band isophotal behavior using the IRAF (Tody 1986, 1993) ellipse task. This task returns the stellar intensity, PA⋆, ellipticity (ε⋆ = 1 − b/a), and deviation from a true ellipse (a4/a) at logarithmically spaced radius intervals. Bad pixel maps were passed into the IRAF task using the primary and dust masks. In Figure 6, we plot changes in PA⋆ and ε⋆ respective to their values at Re. Individual radial PA⋆ and ε⋆ results, as well as the a4/a measurements, are provided in Appendix A.

In Table 3, we report the weighted-average stellar photometric PA⋆, which was calculated as

between Rdust,H and Re. We followed an identical approach to determine the weighted-average . The only exceptions are NGC 612 and NGC 4797, whose Rdust,H are ∼2 Re and Re, respectively, and for which the radial ranges were extended out to 3 Re and 1.5 Re. We also report the degree of isophotal twisting (ΔPA⋆) using the method described by Goullaud et al. (2018):

Here, PAi and PAj are the maximum and minimum stellar PA values from just beyond Rdust,H to near the edge of the H-band mosaic. The range in ellipticity (Δε⋆) was computed in an identical manner. Some of the final ellipse results were not included in these ΔPA⋆ and Δε⋆ ranges due to unusually large uncertainties or considerable discrepancies between neighboring points, most often near the edge of the H-band coverage.

In most cases, photometric twists are small, with over half our targets showing ΔPA⋆ < 20° and only about a fifth reaching ΔPA⋆ > 40°. Figure 6 separates the PA⋆ and ε⋆ responses for different morphological types, with lenticular and elliptical galaxy groups having fairly consistent PA⋆ from Rdust,H to ∼2 Re and Re, respectively. Some systems' PA⋆ and ε⋆ remain flat over the entire WFC3/IR FOV. However, there are some notable exceptions: NGC 3862 shows consistent stellar PA⋆ gradients (and increasingly flattened isophotes) with radius, both within and beyond Re; NGC 612 shows similar behavior that is likely due to recent accretion or a major merger (Emonts et al. 2008; Duah Asabere et al. 2016); and Hydra A shows a consistent PA⋆ beyond ∼2Rdust,H but a rapid ΔPA⋆ ∼ 40° over a radial extent of just 2 kpc. Overall, our sample shows photometric PA behavior similar to that seen in many of the ETGs in the MASSIVE survey (Goullaud et al. 2018), although the latter includes a few cases with more extreme ΔPA⋆.

Unsurprisingly, the largest Δε⋆ are found in lenticular galaxies, whose ε⋆ typically increases from the nucleus to ∼Re due to an increasingly dominant disky stellar component. Beyond ∼Re, the lenticular population trend bifurcates, with ε⋆ continuing to increase for a few galaxies while the majority show negative trends as the more circular stellar halo begins to dominate the isophotal behavior. Elliptical galaxies have more moderate Δε⋆. To quantify the difference between morphological types, we computed the isophotal axis ratio 1 − ε⋆ over the entire radial range for each galaxy to measure the ratio of the maximum/minimum values. The median and scatter in the ratio of extremal 1 − ε⋆ values for elliptical galaxies is 1.19 ± 0.13, while for lenticular galaxies we find a ratio of 1.57 ± 0.42. The typical lenticular galaxy in our sample shows a factor of ∼3 greater change in the isophotal axis ratio than does the typical elliptical galaxy. The half of our sample that have mild isophotal twists (ΔPA⋆ < 20°) but have Δε⋆ ≥ 0.2 correspond to lenticular galaxies, with increasing ε⋆ following the transition from bulge- to disk-dominated regions. In the remaining half with more substantial isophotal twists (ΔPA⋆ > 20°), every case of high Δε⋆ ≥ 0.2 is either a lenticular galaxy or, in the cases of NGC 3862 and NGC 6958, an elliptical galaxy that shows ΔPA⋆ ≳ 45°, which is suggestive of recent merger activity or tidal disruption. In many cases, those lenticular galaxies with high Δε⋆ also show elevated ΔPA⋆ values.

Most of our targets show this good agreement between stellar and CND photometric axes argues either for in situ formation of the CNDs or sufficient elapsed time for gas to settle into the galaxy midplane (of order ∼1 Gyr; e.g., Tran et al. 2001; Lauer et al. 2005; Davis et al. 2013; van de Voort et al. 2015). Despite general agreement, four ETGs show more extreme . As mentioned earlier, the Hydra A only matches PAdust,H near Rdust,H ; for NGC 1387 and NGC 3271, the stellar isophotes always appear to be misaligned; and NGC 5084 appears to have a polar-oriented CND that is a strong candidate for external origin. Still other systems show good agreement out to ∼(1–3) Re, followed by high PA⋆ shifts beyond. This group includes four elliptical galaxies (NGC 3258, NGC 4061, NGC 4786, and NGC 6958) and three lenticular galaxies (NGC 612, NGC 4435, and NGC 6861).

In Table 3, we also include the median a4/a parameter along with its minimum and maximum values over the same radial ranges. Following Rest et al. (2001), we computed isophotal codes (ICs) for radial bins to determine the prevalence of boxy (a4/a < −0.01) and disky (a4/a > +0.01) components through the stellar bulges and into the halos of these luminous ETGs. We find roughly equal numbers of ICs that show neither disky/boxy behavior out to the edge of the H-band FOV and ICs that show some preference for either disky or boxy isophotes. Nearly one in five systems show both disky and boxy behavior, almost always transitioning quickly between the two. Those that show the strongest disky or boxy isophotes (with ∣a4/a∣ > 0.03; NGC 612, NGC 3271, NGC 4373a, NGC 4429, and NGC 4435) are all lenticular galaxies with a very disky stellar component.

4.3. Nuker Fits

To characterize the core versus cuspy nature of our sample, we also fit the H-band stellar surface-brightness profiles with a Nuker profile (Lauer et al. 1995) of the form

This functional form is well suited to model the light distributions of massive elliptical galaxies, which typically follow log-linear behavior. The Nuker profile connects inner and outer power-law slopes γ and β, respectively, with a transition sharpness α at the break radius Rb.

A 2D approach to fitting the stellar surface brightnesses is challenging due to the observed ΔPA⋆ and Δε⋆. Instead, we optimized the Nuker parameters using the isophotal intensity curves shown in Appendix A. Upon inspection, the H-band I(R) of several galaxies shows more complicated behavior that would require additional components (or different parameterizations) for adequate global fits. Since we are primarily concerned with the circumnuclear stellar behavior, we restricted these Nuker fits to radial ranges that best matched a broken power law (generally out to ∼Re). We followed Lauer et al. (1995) in not fitting to the centermost data points (for the WFC3/IR data, points with R ≲ 0 12 were removed) due to potential PSF inaccuracies. We also required Rb > 0

12 were removed) due to potential PSF inaccuracies. We also required Rb > 0 2 to ensure the solutions are robust against HST PSF effects and do not hinge on a singular central data point. To recover intrinsic γ and Rb values from the optimization process, we convolved the model surface-brightness profile with a one-dimensional (1D) approximation of the H-band PSF by extracting the Tiny Tim response along the major axis.

2 to ensure the solutions are robust against HST PSF effects and do not hinge on a singular central data point. To recover intrinsic γ and Rb values from the optimization process, we convolved the model surface-brightness profile with a one-dimensional (1D) approximation of the H-band PSF by extracting the Tiny Tim response along the major axis.

For completeness, we also computed the intrinsic Nuker slope:

at the resolution limit of the H-band data, i.e., at half the PSF FWHM (). Since we have already restricted the Nuker fit to start at this projected distance, it is not surprising that few galaxies in this sample returned . Because of this close agreement in most cases, the statistics discussed below do not depend on the choice of γ or . For a broader range of ETGs, however, γ and are more commonly discrepant (Lauer et al. 2005). Fits to bluer mosaics would allow for more central measurements, but dust would further complicate the interpretation.

The best-fitting Nuker parameters in Table 4 show the outer slopes to be fairly steep, with a median and standard deviation β ∼ 1.6 ± 0.4, although a few cases (especially NGC 612 and NGC 6861) prefer much steeper outer slopes. In every case, we see a distinct break between the inner and outer power-law slopes. Over half our targets have a shallow inner power-law slope with γ ≤ 0.3, often used to identify centrally cored galaxies (Faber et al. 1997). Unsurprisingly for the typically higher stellar masses in our sample, only a few systems show an inner power-law behavior of γ ≥ 0.5. The remainder (nearly a quarter) of the sample are "intermediate" cases with 0.3 < γ < 0.5 (for additional examples, see Ravindranath et al. 2001 and Rest et al. 2001). When split into elliptical and lenticular subclassifications, we find distinct medians γ = 0.04 and 0.31, respectively, but similar overall scatters. This behavior is easily seen in the surface-brightness plots of Figure 7, especially after scaling the isophotal intensities by μb,H and Rb. A restricted analysis of the most cored ETGs (with γ < 0.2) gives a median MK ∼ −25.29 mag that is ∼60% more luminous than for the entire sample. These most cored ETGs also show a closer correspondence between the break radius and CND extent, with a median Rb/adust,H ≈ 1, although individual ratios range from 0.1 to 2.1.

Figure 7. H-band surface-brightness profiles for this ETG sample, showing best-fitting MGE models (left) and the isophotal intensities (right). The isophotal results are normalized to their respective break radii Rb and corresponding surface brightness μb,H , with the (intrinsic) Nuker profiles shown for comparison (inset). Highlighted BCGs/BGGs tend to show lower μb,H , especially for the only BCG, Hydra A. NGC 6861 is the only exception, largely due to its slightly more cuspy profile.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 4. Nuker Fitting Parameters

| Galaxy | μb,H | Rb | α | β | γ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | (mag arcsec−2) | (arcsec) | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

| Hydra A | 16.28 | 1.16 | 3.73 | 1.31 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| NGC 612 | 15.72 | 4.12 | 1.66 | 2.71 | 0.27 | 0.28 |

| NGC 997 | 13.97 | 0.69 | 1.25 | 1.74 | 0.00 | 0.18 |

| NGC 1332 | 13.28 | 1.65 | 0.98 | 1.54 | 0.31 | 0.40 |

| NGC 1387 | 14.35 | 3.25 | 0.98 | 2.23 | 0.37 | 0.44 |

| NGC 3245 | 13.01 | 0.91 | 1.41 | 1.55 | 0.36 | 0.42 |

| NGC 3258 | 14.43 | 1.96 | 1.44 | 1.96 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| NGC 3268 | 14.09 | 1.43 | 2.67 | 1.59 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| NGC 3271 | 14.80 | 3.50 | 5.90 | 1.81 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| NGC 3557 | 13.53 | 1.69 | 1.75 | 1.63 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| NGC 3862 | 14.56 | 1.00 | 2.29 | 1.76 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| NGC 4061 | 14.48 | 0.97 | 1.50 | 1.88 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| NGC 4261 | 13.83 | 1.86 | 2.14 | 1.49 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| NGC 4373a | 12.94 | 0.39 | 2.15 | 1.24 | 0.25 | 0.32 |

| NGC 4429 | 14.34 | 3.51 | 10.00* | 1.26 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| NGC 4435 | 13.63 | 1.76 | 1.11 | 1.66 | 0.23 | 0.30 |

| NGC 4697 | 13.63 | 2.40 | 0.97 | 1.47 | 0.40 | 0.46 |

| NGC 4751 | 12.46 | 0.55 | 2.32 | 1.28 | 0.45 | 0.47 |

| NGC 4786 | 13.58 | 0.65 | 2.99 | 1.24 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| NGC 4797 | 13.55 | 0.24 | 3.01 | 1.20 | 0.27 | 0.37 |

| NGC 5084 | 12.90 | 1.04 | 2.21 | 1.18 | 0.25 | 0.26 |

| NGC 5193 | 14.01 | 1.10 | 2.71 | 1.48 | 0.41 | 0.41 |

| NGC 5208 | 14.84 | 2.47 | 10.00* | 1.35 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| NGC 5838 | 14.34 | 3.01 | 1.15 | 1.82 | 0.64 | 0.67 |

| NGC 6861 | 15.07 | 6.64 | 0.73 | 2.94 | 0.13 | 0.27 |

| NGC 6958 | 12.79 | 0.63 | 1.06 | 1.78 | 0.22 | 0.45 |

Notes. Results of Nuker fits to the H-band isophotal surface-brightness intensities, which account for telescope resolution effects by blurring the intrinsic Nuker function by the Tiny Tim PSF. The above Rb and γ represent the intrinsic break radius and inner power-law slope, respectively. The slope is the slope of the intrinsic Nuker function evaluated at the resolution limit of ∼0 12. Cases denoted with * indicate α was fixed to avoid unphysical solutions.

12. Cases denoted with * indicate α was fixed to avoid unphysical solutions.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

5. Stellar Luminosity Models

We modeled the sky-subtracted H-band surface brightnesses of our galaxies using the MGE formalism (Emsellem et al. 1994), which is convenient for analytical purposes and has been shown to accurately reproduce the stellar profiles of ETGs (see also Cappellari 2002). This series expansion recovers the peak surface brightness (in L⊙ pc−2 units) of each Gaussian component, together with projected dispersions (in arcsec) and axis ratios . In addition to the benefits of the speed and usability of MGEs, this approach also enables simple and efficient convolution with a PSF model to account for blurring effects. In this project, we have employed a 2D concentric MGE and focus on fits that keep the PAs of all Gaussian components tied together during optimization. The ensuing deprojection using the inclination angle i (assuming oblate axisymmetry to determine intrinsic σ and q; Cappellari 2002) then results in an intrinsic stellar luminosity density profile. We note that nonparametric approaches allow for more careful deprojection analysis (e.g., reconstruction of intrinsic densities and comparison of the relative likelihood of different deprojections; de Nicola et al. 2020). Since the ALMA CO kinematics do not typically probe beyond ∼1 kpc and rarely close to Re (Boizelle et al. 2017; Ruffa et al. 2019b; Sansom et al. 2019), however, uncertainties in the deprojection and the large-scale stellar figure are not expected to be of significant concern for gas-dynamical modeling efforts.

We first modeled the 2D surface-brightness values using the MGE method presented by Cappellari (2002), using a linear decomposition to determine initial MGE component numbers and Gaussian parameters. However, the Cappellari (2002) code requires a symmetric approximation to the PSF shape. For our final H-band MGE solutions, we perform the decomposition using the 2D parametric galaxy-fitting algorithm GALFIT (Peng et al. 2010), including the Tiny Tim F160W PSF to account for blurring effects. The final MGE solutions presented in Table 5 include between seven and 16 components. In both MGE approaches, we corrected for foreground Galactic reddening (AGal,H ; Table 1) and employed the primary and dust masks described in Section 3.1 to mitigate the impact of circumnuclear dust during the optimization. The best-fitting MGEs are overlaid on the observed images in zoom-in plots in Figure 5 and nearly full-frame mosaics in Figure 8. Comparisons between 1D surface-brightness profiles extracted from the 2D HST data and MGE models are provided in Appendix A. Three ETGs (NGC 3557, NGC 3862, and NGC 4261) are Fanaroff–Riley type I (or FR-I; i.e., edge-darkened; Fanaroff & Riley 1974) radio galaxies, while another (NGC 4429) is sometimes classified as a low-luminosity AGN (Ho et al. 1997; Nyland et al. 2016). For these targets, preliminary MGE fits preferred the inclusion of nearly unresolved components, which plausibly are due to nonstellar processes. In the final MGEs for these four galaxies, we included PSF components to model and remove possible AGN contributions. Interestingly, only one galaxy (NGC 3862) possesses a prominent H-band point source; for another two (NGC 3557 and NGC 4261), the PSF component is entirely negligible, while for one galaxy (NGC 4429), the point source may represent a very compact stellar component.

Figure 8. Nearly full-frame HST WFC3/F160W mosaics, together with the (dust-masked) GALFIT MGE solutions (overplotted in red) that fit a uniform PA for all components. At larger radii, some galaxies exhibit highly flattened stellar isophotes and/or PA⋆ twists, resulting in unavoidable discrepancies. Contours are shown at logarithmic intensity intervals.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 5. MGE Parameters (with a Uniform PA)

| j | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (L☉ pc−2) | (arcsec) | (L☉ pc−2) | (arcsec) | (L☉ pc−2) | (arcsec) | (L☉ pc−2) | (arcsec) | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| PA = −41.2 | PA = −6.3 | PA = 32.3 | PA = −63.5 | |||||||||

| Hydra A | NGC 612 | NGC 997 | NGC 1332 | |||||||||

| 1 | 3.4550 | 1.1649 | 0.9952 | 4.2391 | 0.1104 | 1.0000 | 4.5670 | 0.2489 | 0.9100 | 5.7035 | 0.1397 | 0.3338 |

| 2 | 2.9155 | 2.9399 | 0.9060 | 4.1763 | 0.3079 | 0.7770 | 4.2751 | 0.7090 | 0.9118 | 4.2340 | 0.2494 | 0.6765 |

| 3 | 2.1662 | 6.4848 | 0.9790 | 3.8616 | 0.5813 | 1.0000 | 3.9212 | 1.4545 | 0.9387 | 4.9782 | 0.4911 | 0.9816 |

| 4 | 2.0350 | 7.2705 | 0.6890 | 3.4430 | 0.9568 | 1.0000 | 3.4301 | 3.1261 | 0.9100 | 4.6117 | 1.5227 | 0.7291 |

| 5 | 2.1566 | 13.133 | 0.7992 | 3.3977 | 2.3868 | 0.6227 | 2.9587 | 6.5902 | 0.9100 | 4.2075 | 3.4156 | 0.7281 |

| 6 | 1.4121 | 26.732 | 0.6940 | 3.4692 | 3.8908 | 0.2553 | 2.4483 | 13.696 | 0.9100 | 3.8332 | 7.3989 | 0.7688 |

| 7 | 0.9438 | 58.893 | 0.6676 | 3.2055 | 5.0384 | 0.5201 | 1.8333 | 33.844 | 0.9260 | 3.1562 | 17.528 | 0.3178 |

| 8 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 2.9094 | 4.9285 | 0.9815 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 3.0689 | 32.944 | 0.2910 |

| 9 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 3.3356 | 4.1166 | 0.2400 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 2.5357 | 52.074 | 0.3259 |

| 10 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 2.3213 | 12.502 | 0.6161 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.8995 | 78.066 | 0.4190 |

| 11 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 2.1723 | 16.296 | 0.9293 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 0.9968 | 165.32 | 0.9901 |

| 12 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.3514 | 40.481 | 1.0000 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| 13 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 0.2425 | 72.318 | 0.9973 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| PA = −73.2 | PA = –4.3 | PA = 74.6 | PA = 69.7 | |||||||||

| NGC 1387 | NGC 3245 | NGC 3258 | NGC 3268 | |||||||||

| 1 | 5.3554 | 0.1517 | 0.9973 | 5.5227 | 0.1388 | 0.6686 | 4.1386 | 0.7662 | 0.9671 | 3.6153 | 0.2802 | 0.6700 |

| 2 | 4.8519 | 0.5218 | 0.9994 | 4.2977 | 0.2578 | 0.5378 | 4.0292 | 1.1586 | 0.7200 | 3.9109 | 0.9996 | 0.9918 |

| 3 | 4.5377 | 1.6441 | 0.9999 | 4.7789 | 0.3163 | 0.5205 | 3.9129 | 2.0040 | 0.7633 | 3.9752 | 1.0794 | 0.7425 |

| 4 | 4.0769 | 4.0668 | 0.9500 | 4.7368 | 0.3776 | 0.9647 | 3.6336 | 2.9726 | 0.8064 | 3.8462 | 1.9852 | 0.7188 |

| 5 | 3.4977 | 7.1948 | 0.9500 | 4.6770 | 0.6348 | 0.8459 | 3.5087 | 4.8344 | 0.8513 | 3.7069 | 2.2767 | 0.8903 |

| 6 | 2.8663 | 14.983 | 0.9500 | 4.5074 | 1.1201 | 0.9631 | 2.6360 | 8.9900 | 0.8158 | 3.4637 | 3.8058 | 0.7805 |

| 7 | 2.4841 | 40.343 | 0.9624 | 4.0375 | 2.5263 | 0.6386 | 2.9576 | 11.511 | 0.9348 | 3.2626 | 6.3293 | 0.8090 |

| 8 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 3.8275 | 3.2671 | 0.7809 | 2.2148 | 22.281 | 0.9800 | 2.8091 | 12.075 | 0.7841 |

| 9 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 3.5080 | 8.9091 | 0.5200 | 2.0012 | 47.787 | 0.7872 | 2.4624 | 21.504 | 0.8048 |

| 10 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 2.9232 | 26.569 | 0.5200 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 2.0247 | 51.639 | 0.7253 |

| 11 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.7579 | 44.971 | 0.5681 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.5208 | 87.993 | 0.9289 |

| 12 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.5658 | 52.299 | 0.6091 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| 13 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.1653 | 162.32 | 0.7948 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| PA = −67.9 | PA = 33.5 | PA = 20.1 | PA = −4.5 | |||||||||

| NGC 3271 | NGC 3557* | NGC 3862* | NGC 4061 | |||||||||

| 1 | 4.9009 | 0.1000 | 0.7376 | 4.2304 | 0.8510 | 0.9866 | 4.1542 | 0.7628 | 0.9900 | 4.1285 | 0.1755 | 0.6600 |

| 2 | 5.1274 | 0.1299 | 0.7300 | 4.3214 | 1.2778 | 0.7500 | 3.7966 | 1.4370 | 0.9940 | 4.2827 | 0.5379 | 0.6600 |

| 3 | 4.5963 | 0.3489 | 0.8362 | 3.9536 | 2.0599 | 0.7500 | 3.4906 | 2.9353 | 0.9910 | 3.7328 | 1.0829 | 0.9533 |

| 4 | 4.2135 | 0.9666 | 0.7307 | 4.0190 | 2.9514 | 0.7500 | 2.7847 | 7.0954 | 0.9933 | 3.6122 | 1.2839 | 0.6600 |

| 5 | 4.0445 | 2.4260 | 0.7300 | 3.7178 | 4.5401 | 0.7613 | 2.2149 | 18.472 | 0.9900 | 3.5582 | 2.1409 | 0.8016 |

| 6 | 3.7112 | 3.8030 | 0.7300 | 3.4740 | 6.8297 | 0.7535 | 1.7046 | 58.754 | 0.9900 | 3.1855 | 3.7517 | 0.8240 |

| 7 | 3.3835 | 6.9061 | 0.7300 | 2.8595 | 11.632 | 0.7500 | PSF mag = 15.86 | 2.4901 | 6.1372 | 0.9569 | ||

| 8 | 2.8441 | 18.027 | 0.7300 | 3.0156 | 13.000 | 0.7500 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 2.2961 | 8.1515 | 0.6600 |

| 9 | 1.9464 | 26.205 | 0.7300 | 2.6283 | 22.466 | 0.7500 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 2.2072 | 12.643 | 0.8367 |

| 10 | 1.8515 | 52.723 | 0.7300 | 2.5442 | 36.827 | 0.7500 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.5922 | 20.997 | 0.7836 |

| 11 | 1.2997 | 74.622 | 0.7300 | 2.0470 | 77.856 | 0.8731 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.5933 | 34.329 | 0.6985 |

| 12 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | PSF mag = 18.08 | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | 1.0584 | 85.239 | 0.7238 | ||