ABSTRACT

For Classical T Tauri Stars (CTTSs), the resonance doublets of N v, Si iv, and C iv, as well as the He ii 1640 Å line, trace hot gas flows and act as diagnostics of the accretion process. In this paper we assemble a large high-resolution, high-sensitivity data set of these lines in CTTSs and Weak T Tauri Stars (WTTSs). The sample comprises 35 stars: 1 Herbig Ae star, 28 CTTSs, and 6 WTTSs. We find that the C iv, Si iv, and N v lines in CTTSs all have similar shapes. We decompose the C iv and He ii lines into broad and narrow Gaussian components (BC and NC). The most common (50%) C iv line morphology in CTTSs is that of a low-velocity NC together with a redshifted BC. For CTTSs, a strong BC is the result of the accretion process. The contribution fraction of the NC to the C iv line flux in CTTSs increases with accretion rate, from ∼20% to up to ∼80%. The velocity centroids of the BCs and NCs are such that VBC ≳ 4 VNC, consistent with the predictions of the accretion shock model, in at most 12 out of 22 CTTSs. We do not find evidence of the post-shock becoming buried in the stellar photosphere due to the pressure of the accretion flow. The He ii CTTSs lines are generally symmetric and narrow, with FWHM and redshifts comparable to those of WTTSs. They are less redshifted than the CTTSs C iv lines, by ∼10 km s−1. The amount of flux in the BC of the He ii line is small compared to that of the C iv line, and we show that this is consistent with models of the pre-shock column emission. Overall, the observations are consistent with the presence of multiple accretion columns with different densities or with accretion models that predict a slow-moving, low-density region in the periphery of the accretion column. For HN Tau A and RW Aur A, most of the C iv line is blueshifted suggesting that the C iv emission is produced by shocks within outflow jets. In our sample, the Herbig Ae star DX Cha is the only object for which we find a P-Cygni profile in the C iv line, which argues for the presence of a hot (105 K) wind. For the overall sample, the Si iv and N v line luminosities are correlated with the C iv line luminosities, although the relationship between Si iv and C iv shows large scatter about a linear relationship and suggests that TW Hya, V4046 Sgr, AA Tau, DF Tau, GM Aur, and V1190 Sco are silicon-poor, while CV Cha, DX Cha, RU Lup, and RW Aur may be silicon-rich.

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS

1. INTRODUCTION

Classical T Tauri stars (CTTSs) are low-mass, young stellar objects surrounded by an accretion disk. They provide us with a laboratory in which to study the interaction between stars, magnetic fields, and accretion disks. In addition to optical and longer wavelength excesses, this interaction is responsible for a strong ultraviolet (UV) excess, Lyα emission, and soft X-ray excesses, all of which have a significant impact on the disk evolution, the rate of planet formation, and the circumstellar environment.

The observed long rotational periods, the large widths of the Balmer lines, and the presence of optical and UV excesses of CTTSs are naturally explained by the magnetospheric accretion paradigm (e.g., Uchida & Shibata 1984; Koenigl 1991; Shu et al. 1994). According to this paradigm, the gas disk is truncated some distance from the star (∼5 R*; Meyer et al. 1997) by the pressure of the stellar magnetosphere. Gas from the disk slides down the stellar gravitational potential along the magnetic field lines, reaching speeds comparable to the free-fall velocity (∼300 km s−1). These velocities are much larger than the local ∼20 km s−1 sound speed (but less than the Alfvén speed of ∼500 km s−1 implied by a 2 kG magnetic field; Johns-Krull 2007). The density of the accretion stream depends on the accretion rate and the filling factor but it is typically of the order of ∼1012 cm−3 (pre-shock; see Calvet & Gullbring 1998). The supersonic flow, confined by the magnetic field, produces a strong shock upon reaching the star, which converts most of the kinetic energy of the gas into thermal energy (e.g., Lamzin 1995).

The gas reaches temperatures of the order of a million degrees at the shock surface and cools radiatively until it merges with the stellar photosphere. Part of the cooling radiation will heat the stellar surface, resulting in a hot spot, observed spectroscopically as an excess continuum (the "veiling"). Cooling radiation emitted away from the star will illuminate gas before the shock surface, producing a radiative precursor of warm (T ∼ 104 K), ionized gas (Calvet & Gullbring 1998). In this paper we will use the term "accretion shock region" as shorthand for the region that includes the pre-shock, the shock surface, the post-shock column, and the heated photosphere.

Because the accretion column should be in pressure equilibrium with the stellar photosphere, Drake (2005) suggested that for typical accretion rates (∼10−8 M☉ yr−1) the post-shock region would be buried, in the sense that the shortest escape paths for post-shock photons would go through a significant column of photospheric gas. Sacco et al. (2010) have argued that the burying effects appear at accretion rates as small as a few times ∼10−10 M☉ yr−1 and that absorption of the X-rays by the stellar photosphere may explain the one to two orders of magnitude discrepancy between the accretion rates calculated from X-ray line emission and those calculated from optical veiling or near-UV excesses, and the lack of dense (ne ≳ 1011 cm−3) X-ray-emitting plasma in objects such as T Tau (Güdel et al. 2007).

Time-dependent models of the accretion column by Sacco et al. (2008) predict that emission from a single, homogeneous, magnetically dominated post-shock column should be quasi-periodic, on timescales of ∼400 s, because plasma instabilities can collapse the column. Such periodicity has not been observed (Drake et al. 2009; Günther et al. 2010), perhaps suggesting that accretion streams are inhomogeneous, or that there are multiple, uncorrelated accretion columns.

Observations during the last two decades have resulted in spectroscopic and photometric evidence for the presence of accretion hot spots or rings with filling factors of up to a few percent (see review by Bouvier et al. 2007). The surface topology of the magnetic field (e.g., Gregory et al. 2006; Mohanty & Shu 2008) and/or the misalignment between the rotational and magnetic axes result in a rotationally modulated surface flux (Johns & Basri 1995; Argiroffi et al. 2011, 2012), with a small filling factor (Calvet & Gullbring 1998; Valenti & Johns-Krull 2004). The spots appear and disappear over timescales of days (Rucinski et al. 2008) to years (Bouvier et al. 1993). Analysis of the possible magnetic field configurations indicates that although CTTSs have very complex surface magnetic fields, the portion of the field that carries gas from the inner disk to the star, is well ordered globally (Johns-Krull et al. 1999a; Adams & Gregory 2012).

In this paper we use the strong emission lines of ionized metals in order to probe the characteristics of the accretion shock region. In particular, we are interested in understanding the role that accretion has in shaping these lines, where the lines originate, and what the lines reveal about the geometry of the accretion process. Our long-term goal is to clarify the UV evolution of young stars and its impact on the surrounding accretion disk.

We analyze the resonance doublets of N v (λλ1238.82, 1242.80), Si iv (λλ1393.76, 1402.77), and C iv (λλ1548.19, 1550.77), as well as the He ii (λ1640.47) line. If they are produced by collisional excitation in a low-density medium, their presence suggests a high temperature (∼105 K, assuming collisional ionization equilibrium) or a photoionized environment. In solar-type main sequence stars, these "hot" lines are formed in the transition region, the narrow region between the chromosphere and the corona, and they are sometimes called transition-region lines.

The C iv resonance doublet lines are among the strongest lines in the UV spectra of CTTSs (Ardila et al. 2002). Using International Ultraviolet Explorer (IUE) data, Johns-Krull et al. (2000) showed that the surface flux in the C iv resonant lines can be as much as an order of magnitude larger than the largest flux observed in Weak T Tauri stars (WTTSs), main sequence dwarfs, or RS CVn stars. They also showed that the high surface flux in the C iv lines of CTTSs is uncorrelated with measures of stellar activity but it is strongly correlated with accretion rate, for accretion rates from 10−8 M☉ yr−1 to 10−5 M☉ yr−1. The strong correlations among accretion rate, C iv flux, and far-ultraviolet (FUV) luminosity have been confirmed by Ingleby et al. (2011) and Yang et al. (2012) using Advanced Camera for Surveys Solar Blind Channel (ACS/SBC) and Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) data. Those results further suggest a causal relationship between the accretion process and the hot line flux.

Previous surveys of the UV emission lines in low-resolution spectra of T Tauri stars include the analysis of IUE spectra (Valenti et al. 2000; Johns-Krull et al. 2000) and Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph (GHRS), ACS, and STIS spectra (Yang et al. 2012). Prior analysis of high resolution observations of the hot gas lines in T Tauri stars had been published for some objects (BP Tau, DF Tau, DG Tau, DR Tau, EG Cha, EP Cha, GM Aur, RU Lup, RW Aur A, RY Tau, T Tau, TW Hya, TWA 5, V4046 Sgr, and HBC 388; see Lamzin 2000a, 2000b; Errico et al. 2000, 2001; Ardila et al. 2002; Herczeg et al. 2002, 2005, 2006; Lamzin et al. 2004; Günther & Schmitt 2008; Ingleby et al. 2011). In addition, analysis of the C iv lines for the brown dwarf 2M1207 has been published by France et al. (2010). The observations show that the C iv lines in CTTSs have asymmetric shapes and wings that often extend to ±400 km s−1 from the line rest velocity. The emission lines are mostly centered or redshifted, although some stars occasionally present strong blueshifted emission (e.g., DG Tau, DR Tau, and RY Tau). Doublet ratios are not always 2:1 (e.g., DG Tau, DR Tau, RU Lup, and RW Aur A). Overall, the UV spectra of CTTSs also show large numbers of narrow H2 emission lines and CO bands in absorption and emission (France et al. 2011; Schindhelm et al. 2012), produced primarily by Lyα fluorescence. In most observations published so far, the Si iv line is strongly contaminated by H2 lines, and the N v 1243 Å line is absorbed by circumstellar or interstellar N i. High spectral resolution observations are crucial to fully exploit the diagnostic power of the UV observations as the H2 emission lines can be kinematically separated from the hot lines only when the resolution is high enough. In addition, we will show here that the hot gas lines have multiple kinematic components that can only be analyzed in high resolution spectra.

Both the correlation between accretion rate and C iv surface flux and the presence of redshifted hot gas line profiles in some stars, are consistent with formation in a high-latitude accretion flow. However, according to Lamzin (2003a, 2003b) C iv line formation in the accretion shock region should result in double-peaked line profiles, which are generally not observed. In this context Günther & Schmitt (2008) explored the shape of the hot gas lines (primarily O vi and C iv) in a sample of seven stars. They considered formation in the accretion shock, in an outflow, in the surface of the disk, in an equatorial boundary layer, and in the stellar transition region, and concluded that no single explanation or region can be responsible for all the observed line characteristics. In particular, they concluded that the shape of the redshifted lines was incompatible with models of magnetospheric accretion.

With the primary goal of providing a unified description of the hot gas lines and understanding their origin, we have obtained FUV and near-ultraviolet (NUV) spectra of a large sample of CTTSs and WTTSs, using the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) and the STIS. Most of the data for this paper comes from the Cycle 17 Hubble Space Telescope (HST) proposal "The Disks, Accretion, and Outflows (DAO) of T Tau stars" (PI: G. Herczeg; Prop. ID: HST-GO-11616). The DAO program is the largest and most sensitive high resolution spectroscopic survey of young stars in the UV ever undertaken and as such it provides a rich source of information for these objects. The program is described in more detail in G. Herczeg et al. (2013, in preparation). We have complemented the DAO data with GTO data from HST programs 11533 and 12036 (PI: J. Green; BP Tau, DF Tau, RU Lup, V4046 Sgr) as well as UV spectra from the literature and from the Mikulski Archive at STScI (Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes, MAST).

As shown below, there is a wide diversity of profiles in all lines for the stars in our sample. The spectra are rich and a single paper cannot do justice to their variety nor to all the physical mechanisms that likely contribute to their formation. Here we take a broad view in an attempt to obtain general statements about accretion in CTTSs. Details about the sample and the data reduction are presented in Section 2. We then analyze the C iv, Si iv, He ii, and N v lines. The analysis of the C iv lines takes up most of the paper, as this is the strongest line in the set, and the least affected by absorptions or emissions by other species (Section 5). We examine the line shapes, the relationship with accretion rate, and correlations among quantities associated with the lines and other CTTSs parameters. We also obtain from the literature multi-epoch information on line variability (Section 5.4). The other lines play a supporting role in this analysis and are examined in Sections 6 and 7. Section 8 contains a summary of the observational conclusions and a discussion of their implications. The conclusions are in Section 9.

2. OBSERVATIONS

Tables 1–3 list the 35 stars we will be analyzing in this paper and the references for all the ancillary data we consider. Table 4 indicates the origin of the data (DAO or some other project), the data sets, and slit sizes used for the observations. Details about exposure times will appear in G. Herczeg et al. (2013, in preparation).

Table 1. Stars Analyzed in This Paper

| Name a | Alternate Name | Region | d | SpT b | Ref. SpT | Av | Ref. Av |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (pc) | (mag) | ||||||

| Classical T Tauri Stars | |||||||

| AA Tau | HBC 63 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K7 | Donati et al. (2010) | 0.74 | Gullbring et al. (1998) |

| AK Sco | HBC 271 | Upper-Scorpius | 145 | F5+F5 | Andersen et al. (1989) | 0.5 | Alencar et al. (2003) |

| BP Tau | HBC 32 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K7 | Johns-Krull et al. (1999b) | 0.5 | Gullbring et al. (1998) |

| CV Cha | HBC 247 | Chamaeleon I | 160 | G8 | Guenther et al. (2007) | 1.5 | Furlan et al. (2009) |

| CY Tau | HBC 28 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | M1 | Hartmann et al. (1998) | 0.32 | Gullbring et al. (1998) |

| DE Tau | HBC 33 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | M0 | Furlan et al. (2009) | 0.62 | Gullbring et al. (1998) |

| DF Tau | HBC 36 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | M2+? | Herczeg et al. (2006) | 0.6 | Herczeg et al. (2006) |

| DK Tau | HBC 45 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K7 | Furlan et al. (2009) | 1.42 | Gullbring et al. (1998) |

| DN Tau | HBC 65 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | M0 | Furlan et al. (2009) | 0.25 | Gullbring et al. (1998) |

| DR Tau | HBC 74 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K7 | Petrov et al. (2011) | 1.2 | Gullbring et al. (2000) |

| DS Tau | HBC 75 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K5 | Muzerolle et al. (1998) | 0.34 | Gullbring et al. (1998) |

| DX Cha | HD 104237 |  Chamaeleontis Chamaeleontis | 114 | A7.5+K3 | Böhm et al. (2004) | 0.56 | Sartori et al. (2003) |

| EP Cha | RECX 11 | η Chamaeleontis | 97 | K4 | Mamajek et al. (1999) | 0 | Ingleby et al. (2013) |

| ET Cha | RECX 15 | η Chamaeleontis | 97 | M2 | Lawson et al. (2002) | 0 | Ingleby et al. (2013) |

| HN Tau A | HBC 60 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K5 | Furlan et al. (2009) | 0.65 | Gullbring et al. (1998) |

| MP Mus | PDS 66 | Isolated? | 100 | K1 | Torres et al. (2006) | 0.17 | Mamajek et al. (2002) |

| RU Lup | HBC 251 | Lupus I | 150 | K7 | Herczeg et al. (2005) | 0.1 | Herczeg et al. (2006) |

| RW Aur A | HBC 80 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K4+? | Johns-Krull et al. (1999b) | 1.2 | Valenti et al. (1993) |

| SU Aur | HBC 79 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | G1 | Furlan et al. (2009) | 0.9 | Gullbring et al. (2000) |

| T Tau N | HBC 35 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K1 | Walter et al. (2003) | 0.3 | Walter et al. (2003) |

| V1190 Sco | HBC 617; Sz 102 | Upper Scorpius | 145 | K0 | Hughes et al. (1994) | 0.32 | Sartori et al. (2003) |

| V4046 Sgr | HBC 662 | β Pictoris | 72 | K5+K7 | Quast et al. (2000) | 0 | Curran et al. (2011) |

| Transition Disks | |||||||

| CS Cha | HBC 569 | Chamaeleon I | 160 | K6+? | Luhman (2004) | 0.3 | Furlan et al. (2009) |

| DM Tau | HBC 62 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | M1.5 | Espaillat et al. (2010) | 0.6 | Ingleby et al. (2009) |

| GM Aur | HBC 77 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K5.5 | Espaillat et al. (2010) | 0.31 | Gullbring et al. (1998) |

| IP Tau | HBC 385 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | M0 | Furlan et al. (2009) | 0.32 | Gullbring et al. (1998) |

| TW Hya | HBC 568 | TW Hydrae Association | 55 | K6 | Torres et al. (2006) | 0.0 | Herczeg et al. (2004) |

| UX Tau A | HBC 43 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K2 | Herbig (1977) | 0.7 | Furlan et al. (2009) |

| V1079 Tau | LkCa 15; HBC 419 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K3 | Espaillat et al. (2010) | 1.00 | White & Ghez (2001) |

| Weak T Tauri Stars | |||||||

| EG Cha | RECX 1 | η Chamaeleontis | 97 | K4+? | Mamajek et al. (1999) | 0 | Ingleby et al. (2013) |

| TWA 7 | 2MASS J1042-3340 | TW Hydrae Association | 55 | M2 | Torres et al. (2006) | 0 | Ingleby et al. (2009) |

| V1068 Tau | LkCa 4; HBC 370 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K7 | Herbig & Bell (1988) | 0.69 | Bertout (2007) |

| V396 Aur | LkCa 19; HD 282630 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K0 | Herbig & Bell (1988) | 0 | Walter et al. (1988) |

| V397 Aur | HBC 427 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K7+M2 | Steffen et al. (2001) | 0.0 | Kenyon & Hartmann (1995) |

| V410 Tau | HBC 29 | Taurus-Auriga | 140 | K2 (A) +M? (B) | Stelzer et al. (2003) | 0.03 | Bertout (2007) |

Notes. aIn this paper we refer to the stars with their variable star name, if it exists. The exception is TWA 7, which does not have a variable star name. bFor binary stars, the spectral type refers to the primary component, unless indicated.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

Table 2. Ancillary Data

| Name | Radial Velocity | Ref. Rad. Vel. | Inc. a | Ref. Inc. | Binarity b | Ref. Binarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (km s−1) | (deg) | |||||

| Classical T Tauri Stars | ||||||

| AA Tau | 16.5 | Bouvier et al. (1999) | 70 ± 10 | Donati et al. (2010) | S | Najita et al. (2007) |

| AK Sco | −1.15 | Andersen et al. (1989) | 63 | Andersen et al. (1989) | 2 (SB) | Alencar et al. (2003) |

| BP Tau | 15.8 | Hartmann et al. (1986) | ∼45 | Donati et al. (2008) | S | Leinert et al. (1993) |

| CV Cha | 16.1 | Guenther et al. (2007) | 35 ± 10 | Hussain et al. (2009) | S | Melo (2003) |

| CY Tau | 19.1 | Hartmann et al. (1986) | 47 ± 8 | Simon et al. (2000) | S | Najita et al. (2007) |

| DE Tau | 14.9 | Hartmann et al. (1986) | 57 | Appenzeller et al. (2005) | S | Najita et al. (2007) |

| DF Tau | 11.0 | Edwards et al. (1987) | 50 | Appenzeller et al. (2005) | 2 (0 09) 09) | Ghez et al. (1993) |

| DK Tau | 15.3 | Hartmann et al. (1986) | 44 | Appenzeller et al. (2005) | 2 (2 304) 304) | Correia et al. (2006) |

| DN Tau | 16.1 | Hartmann et al. (1986) | 30 | Appenzeller et al. (2005) | S | Najita et al. (2007) |

| DR Tau | 27.6 | Alencar & Basri (2000) | 20 ± 4 | Petrov et al. (2011) | S | Leinert et al. (1993) |

| DS Tau | 16.3 | Hartmann et al. (1986) | ∼90 | Derived from | S | Najita et al. (2007) |

| Kundurthy et al. (2006) | ||||||

| Glebocki & Gnacinski (2005) | ||||||

| DX Cha | 13 | Kharchenko et al. (2007); | 18 | Grady et al. (2004) | 2 (SB) | Böhm et al. (2004) |

| EP Cha (RECX 11) | 18 | Assumed to be as EG Cha | N/A | ... | S | Brandeker et al. (2006) |

| ET Cha (RECX 15) | 15.9 | Barbier-Brossat & Figon (2000) | 40 | Woitke et al. (2011) | S | Woitke et al. (2011) |

| HN Tau A | 4.6 | Nguyen et al. (2012) | N/A | ... | 2 (A-B: 3 109) 109) | Correia et al. (2006) |

| MP Mus | 11.6 | Torres et al. (2006) | 32 | Curran et al. (2011) | S | Curran et al. (2011) |

| RU Lup | −0.9 | Melo (2003) | 24 | Herczeg et al. (2005) | S | Lamzin (1995) |

| RW Aur A | 14.0 | Hartmann et al. (1986) | 37 | Appenzeller et al. (2005) | M | Gahm et al. (1999); |

(Aa-Ab: 0 01; AaAb-BC: 1 01; AaAb-BC: 1 41) 41) | Correia et al. (2006) | |||||

| SU Aur | 9.7 | Hartmann et al. (1986) | 52 ± 10 | Akeson et al. (2005) | S | Nguyen et al. (2012) |

| T Tau N | 19 | Hartmann et al. (1986) | 19 | Herbst et al. (1997) | 2 (0 7) 7) | Dyck et al. (1982) |

| V1190 Sco | 5.0 | Graham & Heyer (1988) | <5 | Comerón & Fernández (2010) | N/A | ... |

| V4046 Sgr | −6.94 | Quast et al. (2000) | 35 | Quast et al. (2000) | 2 (SB) | Quast et al. (2000) |

| Transition Disks | ||||||

| CS Cha | 15.0 | Reipurth & Cernicharo (1995) | 60 | Espaillat et al. (2011) | 2 (SB)? c | Guenther et al. (2007) |

| DM Tau | 16.9 | Hartmann et al. (1986) | 45 ± 5 | Simon et al. (2000) | S | Najita et al. (2007) |

| GM Aur | 14.8 | Simon et al. (2000) | 54 ± 5 | Simon et al. (2000) | S | Najita et al. (2007) |

| IP Tau | 14.8 | Hartmann et al. (1987) | 30 | Derived from | S | Najita et al. (2007) |

| Glebocki & Gnacinski (2005) | ||||||

| Glebocki & Gnacinski (2005) | ||||||

| TW Hya | 13.5 | Sterzik et al. (1999); | 18 ± 10 | Herczeg et al. (2002) | S | Curran et al. (2011) |

| measured by Herczeg et al. (2002) | ||||||

| UX Tau A | 22.9 | Kharchenko et al. (2007); | 49 | Andrews et al. (2011) | S | Najita et al. (2007) |

| V1079 Tau (LkCa 15) | 17.0 | Hartmann et al. (1987) | 42 ± 5 | Simon et al. (2000) | S | Najita et al. (2007) |

| Weak T Tauri Stars | ||||||

| EG Cha (RECX 1) | 18 | Malaroda et al. (2000); | N/A | ... | M | Köhler & Petr-Gotzens (2002) |

(AB 0 18; AB-C: 8 18; AB-C: 8 6) 6) | ||||||

| TWA 7 | 10.6 | Kharchenko et al. (2007); | N/A | ... | S | Lowrance et al. (2005) |

| V1068 Tau (LkCa 4) | 16.9 | Hartmann et al. (1987) | N/A | ... | S | Najita et al. (2007) |

| V396 Aur (LkCa 19) | 14.3 | Hartmann et al. (1987) | N/A | ... | S | Najita et al. (2007) |

| V397 Aur | 15.0 | Walter et al. (1988) | N/A | ... | 2 (0 0328) 0328) | Steffen et al. (2001) |

| V410 Tau | 17.8 | Hartmann et al. (1986) | N/A | ... | M | Correia et al. (2006) |

(AB: 0 07; AB-C: 0 07; AB-C: 0 290) 290) | ||||||

Notes. aInclination from face-on (=0°). When inclination is listed as "Derived from" we have derived it from the reported v*sin i, the period, and the stellar radius. bBinarity: S, single; M, multiple; SB, spectroscopic binary. The number in parenthesis indicates the separation of the components. cPossible spectroscopic long-period (>2482 days) binary. Unknown companion characteristics (Guenther et al. 2007).

Download table as: ASCIITypeset images: Typeset image Typeset image

Table 3. Ancillary Data

| Name |

| Ref.

| Simult.  ?

a ?

a

|

|---|---|---|---|

| (10−8 M☉ yr−1) | Y/N | ||

| Classical T Tauri Stars | |||

| AA Tau | 1.3 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| AK Sco | 1 | Assumed b | N |

| BP Tau | 2.9 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | N |

| CV Cha | 3.5 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | N |

| CY Tau | 0.75 | Gullbring et al. (1998) | N |

| DE Tau | 2.6 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| DF Tau | 3.45 | Herczeg et al. (2006) - Average | N |

| DK Tau | 3.5 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| DN Tau | 1.0 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| DR Tau | 5.2 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| DS Tau | 1.3 | Gullbring et al. (1998) | N |

| DX Cha | 3.55 | Garcia Lopez et al. (2006) | N |

| EP Cha (RECX 11) | 0.017 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| ET Cha (RECX 15) | 0.042 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| HN Tau A | 1.4 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| MP Mus | 0.045 | Curran et al. (2011) | N |

| RU Lup | 1.8 | Herczeg et al. (2006) | N |

| RW Aur A | 2 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| SU Aur | 0.55 | Calvet et al. (2004) | N |

| T Tau N | 4.45 | Calvet et al. (2004) | N |

| V1190 Sco | 0.79 | Güdel et al. (2010) | N |

| V4046 Sgr | 0.060 | Curran et al. (2011) | N |

| Transition Disks | |||

| CS Cha | 0.53 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| DM Tau | 0.22 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| GM Aur | 0.96 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| IP Tau | 0.48 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| TW Hya | 0.15 | Herczeg et al. (2004) - Average | N |

| UX Tau A | 1.1 | Espaillat et al. (2010) | N |

| V1079 Tau (LkCa 15) | 0.31 | Ingleby et al. (2013) | Y |

| Weak T Tauri Stars | |||

| EG Cha (RECX 1) | ... | ... | ... |

| TWA 7 | ... | ... | ... |

| V1068 Tau (LkCa 4) | ... | ... | ... |

| V396 Aur (LkCa 19) | ... | ... | ... |

| V397 Aur | ... | ... | ... |

| V410 Tau | ... | ... | ... |

Notes.

aSimultaneous (within ∼10 hr) near- and far-ultraviolet observations are available for some of the DAO targets (G. Herczeg et al. 2013, in preparation). The last column indicates whether simultaneous NUV observations were used to calculate the accretion rate, as described in Ingleby et al. (2013). bWe assume  = 1 × 10−8

M☉ yr−1 for AK Sco (Gómez de Castro 2009).

= 1 × 10−8

M☉ yr−1 for AK Sco (Gómez de Castro 2009).

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

Table 4. Data Sources

| Name | FUV a | FUV Data Set b | FUV Slit c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical T Tauri Stars | |||

| AA Tau | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B070XX | PSA |

| AK Sco | DAO: STIS E140M | OB6B21040 | 0 2 × 0 2 × 0 2 2 |

| BP Tau | GTO 12036: COS G130M; G160M | LBGJ010XX | PSA |

| CV Cha | DAO: STIS E140M | OB6B180XX | 0 2 × 0 2 × 0 2 2 |

| CY Tau | GO 8206: STIS E140M | O5CF030XX | 0 2 × 0 2 × 0 2 2 |

| DE Tau | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B080XX | PSA |

| DF Tau | GTO 11533: COS G130M; G160M | LB3Q020XX | PSA |

| DK Tau | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B120XX | PSA |

| DN Tau | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B040XX | PSA |

| DR Tau | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B140XX | PSA |

| DS Tau | GO 8206: STIS E140M | O5CF010XX | 0 2 × 0 2 × 0 2 2 |

| DX Cha | DAO: STIS E140M | OB6B25050 | 0 2 × 0 2 × 0 2 2 |

| EP Cha | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B240XX | PSA |

| ET Cha | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B170XX | PSA |

| HN Tau A | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B090XX | PSA |

| MP Mus | DAO: STIS E140M | OB6B230XX | 0 2 × 0 2 × 0 2 2 |

| RU Lup | GTO 12036: COS G130M; G160M | LBGJ020XX | PSA |

| RW Aur | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B150XX | PSA |

| SU Aur | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B110XX | PSA |

| T Tau | GO 8157: STIS E140M | O5E3040XX | 0 2 × 0 2 × 0 06 06 |

| V1190 Sco | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B590XX | PSA |

| V4046 Sgr | GTO 11533: COS G130M; G160M | LB3Q010XX | PSA |

| Transition Disks | |||

| CS Cha | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B160XX | PSA |

| DM Tau | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B020XX | PSA |

| GM Aur | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B010XX | PSA |

| IP Tau | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B050XX | PSA |

| TW Hya | GO 11608: STIS E140M | OB3R070XX | 0 2 × 0 2 × 0 2 2 |

| UX Tau A | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B530XX | PSA |

| V1079 Tau | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B030XX | PSA |

| Weak T Tauri Stars | |||

| EG Cha | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B320XX | PSA |

| TWA 7 | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B300XX | PSA |

| V1068 Tau | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B270XX | PSA |

| V396 Aur | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B280XX | PSA |

| V397 Aur | DAO: COS G130M; G160M | LB6B260XX | PSA |

| V410 Tau | GO 8157: STIS E140M | O5E3080XX | 0 2 × 0 2 × 0 06 06 |

Notes.

aIn addition to the DAO data, we have made use of data from the following HST proposals: GO 8157: Molecular Hydrogen in the Circumstellar Environments of T Tauri Stars (PI: Walter); GO 8206: The Structure of the Accretion Flow on pre-main-sequence stars (PI: Calvet); GTO 11533: Accretion Flows and Winds of Pre-Main Sequence Stars (PI: Green); GO 11608: How Far Does H2 Go: Constraining FUV Variability in the Gaseous Inner Holes of Protoplanetary Disks (PI: Calvet); GTO 12036: Accretion Flows and Winds of Pre-Main Sequence Stars Part 2 (PI: Green). bThe data set columns indicate the suffix or the full name (if only one) of the HST data set used. cPSA: primary science aperture (for COS), 2 5 diameter. For the STIS data the slit size used is indicated.

5 diameter. For the STIS data the slit size used is indicated.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

The data considered here encompass most of the published high resolution HST observations of the C iv doublet lines for CTTSs. Ardila et al. (2002) provide references to additional high-resolution C iv data for CTTSs obtained with the GHRS. We do not re-analyze those spectra here, but they provide additional context to our paper. Non-DAO STIS data were downloaded from the HST STIS Echelle Spectral Catalog of Stars (StarCAT; Ayres 2010). Non-DAO COS data were downloaded from the MAST and reduced as described below.

The sample of stars considered here includes objects with spectral types ranging from A7 (the Herbig Ae star DX Cha

18

) to M2, although most objects have mid-K spectral types. We assume stellar ages and distances to be ∼2 Myr and 140 pc, respectively, for Taurus-Aurigae (see Loinard et al. 2007 and references therein), ∼2 Myr and 150 pc for Lupus I (Comerón et al. 2009), ∼5 Myr and 145 pc for Upper-Scorpius (see Alencar et al. 2003 and references therein), ∼5 Myr and 114 pc for the  Chamaeleontis cluster (see Lyo et al. 2008 and references therein), ∼5 Myr and 160 pc for Chamaeleon I (see Hussain et al. 2009 and references therein), ∼8 Myr and 97 pc for the η Chamaeleontis cluster (Mamajek et al. 1999), ∼10 Myr and 55 pc for the TW Hydrae association (Zuckerman & Song 2004), and ∼12 Myr and 72 pc for V4046Sgr in the β Pictoris moving group (Torres et al. 2006). The sample includes MP Mus (∼7 Myr and 100 pc; Kastner et al. 2010 and references therein), not known to be associated with any young region.

Chamaeleontis cluster (see Lyo et al. 2008 and references therein), ∼5 Myr and 160 pc for Chamaeleon I (see Hussain et al. 2009 and references therein), ∼8 Myr and 97 pc for the η Chamaeleontis cluster (Mamajek et al. 1999), ∼10 Myr and 55 pc for the TW Hydrae association (Zuckerman & Song 2004), and ∼12 Myr and 72 pc for V4046Sgr in the β Pictoris moving group (Torres et al. 2006). The sample includes MP Mus (∼7 Myr and 100 pc; Kastner et al. 2010 and references therein), not known to be associated with any young region.

The sample includes stars with transition disks (TDs; Espaillat et al. 2011) CS Cha, DM Tau, GM Aur, IP Tau, TW Hya, UX Tau A, and V1079 Tau (LkCa 15). Here we take the term "transition disk" to mean a disk showing infrared evidence of a hole or a gap. As a group, TDs may have lower accretion rates than other CTTS disks (Espaillat et al. 2012). However, for the targets included here the difference between the accretion rates of TDs and those of the rest of the accreting stars is not significant. The sample also includes six Weak T Tauri Stars (WTTSs): EG Cha (RECX 1), V396 Aur (LkCa 19), V1068 Tau (LkCa 4), TWA 7, V397 Aur, and V410 Tau.

Of the 35 stars considered here, 12 are known to be part of binary systems. Dynamical interactions among the binary components may re-arrange the circumstellar disk or preclude its existence altogether. The presence of an unaccounted for companion may result in larger-than-expected accretion diagnostic lines. In addition, large instantaneous radial velocities may be observed in the targeted lines at certain points of the binary orbit.

AK Sco, DX Cha, and V4046 Sgr are spectroscopic binaries with circumbinary and/or circumstellar disks. CS Cha is a candidate long-period spectroscopic binary, although the characteristics of the companion are unknown (Guenther et al. 2007). The accretion rates listed in Table 3 are obtained from optical veiling and NUV excesses and represent total accretion for the overall system. At the end of this paper we will conclude that binarity may be affecting the line centroid determination only in AK Sco.

For non-spectroscopic binaries, the effect of the binarity may be relevant only if both companions are within the COS or STIS apertures. This is the case for DF Tau, RW Aur A, and the WTTSs EG Cha, V397 Aur, and V410 Tau. For DF Tau and RW Aur A, the primary component dominates the FUV emission (see Herczeg et al. 2006; Alencar et al. 2005).

Table 3 lists the accretion rate, obtained from literature sources. For some stars, the DAO data set contains simultaneous NUV and FUV observations, obtained during the same HST visit. Ingleby et al. (2013) describe those NUV observations in more detail and calculate accretion rates based on them. In turn, we use those accretion rate determinations here. The uncertainty in the accretion rate is dominated by systematic factors such as the adopted extinction correction and the color of the underlying photosphere. These may result in errors as large as a factor of 10 in the accretion rate. We do not list vsin i measurements for the sample but typical values for young stars are ∼10–20 km s−1 (Basri & Batalha 1990).

2.1. Data Reduction

The COS and STIS DAO data were all taken in time-tagged mode.

- 1.COS observations. The FUV (1150–1790 Å) spectra were recorded using multiple exposures with the G130M grating (1291, 1327 Å settings) and the G160M grating (1577, 1600, 1623 Å settings). These provide a velocity resolution of Δv ∼ 17 km s−1 (R ∼ 17,000) with seven pixels per resolution element (Osterman et al. 2011; Green et al. 2012).The maximum exposure time was accumulated in the region of the Si iv resonance lines and the exposures ranged from 3 ks (for most stars with two-orbit visits) to a maximum of 8 ks for a few stars with four-orbit visits. Use of multiple grating positions ensured full wavelength coverage and reduced the effects of fixed pattern noise.All observations were taken using the primary science aperture (PSA), which is a 2

5 diameter circular aperture. The acquisition observations used the ACQ/SEARCH algorithm followed by ACQ/IMAGE (Dixon & the COS/STIS Team 2011). The absolute wavelength scale accuracy is ∼15 km s−1 (1σ), where the error is dominated by pointing errors. We obtained one dimensional, co-added spectra using the COS calibration pipeline (CALCOS) with alignment and co-addition obtained using the IDL routines described by Danforth et al. (2010).

5 diameter circular aperture. The acquisition observations used the ACQ/SEARCH algorithm followed by ACQ/IMAGE (Dixon & the COS/STIS Team 2011). The absolute wavelength scale accuracy is ∼15 km s−1 (1σ), where the error is dominated by pointing errors. We obtained one dimensional, co-added spectra using the COS calibration pipeline (CALCOS) with alignment and co-addition obtained using the IDL routines described by Danforth et al. (2010). - 2.STIS observations. Those targets that are too bright to be observed by COS were observed using the STIS E140M echelle grating, which has a spectral resolution of Δv ∼ 7 km s−1 (R ∼ 45,000), over the region 1150–1700 Å. All the observations were obtained using the 0

2 × 0

2 × 0 2 "photometric" aperture, during two HST orbits.The STIS FUV spectra were calibrated and the echelle orders co-added to provide a single spectrum using the IDL software package developed for the StarCAT project (Ayres 2010). This reduction procedure provides a wavelength-scale accuracy of 1σ = 3 km s−1. Non-DAO STIS data were taken directly from StarCAT.

2 "photometric" aperture, during two HST orbits.The STIS FUV spectra were calibrated and the echelle orders co-added to provide a single spectrum using the IDL software package developed for the StarCAT project (Ayres 2010). This reduction procedure provides a wavelength-scale accuracy of 1σ = 3 km s−1. Non-DAO STIS data were taken directly from StarCAT.

For a given pointing, errors in the positioning of the target within the aperture result in an offset in the wavelength scale. As indicated above, these are supposed to be 15 km s−1 for COS and 3 km s−1 for STIS, according to the instrument observing manuals (Dixon & the COS/STIS Team 2011; Ely & the COS/STIS Team 2011). In addition, the geometric correction necessary to account for the curvature of the COS FUV detector may make longer wavelength features appear redder than they really are. The offset depends on the exact position of the target on the detector. In most cases this intra-spectrum wavelength uncertainty is <10 km s−1, but in a few extreme cases it will introduce a ∼15 km s−1 shift from the reddest to the bluest wavelengths in a single COS grating mode (see Figure 4 from Linsky et al. 2012).

To determine how important the errors due to pointing and calibration are in the COS data, we focus on the H2 lines. We use the line measurements from K. France (2013, private communication; see also France et al. 2012) for P(2)(0–5) at 1398.95 Å, R(11)(2–8) at 1555.89 Å, R(6)(1–8) at 1556.87 Å, and P(5)(4–11) at 1613.72 Å. France et al. (2012) show that in the case of DK Tau, ET Cha (RECX 15), HN Tau, IP Tau, RU Lup, RW Aur, and V1079 Tau (LkCa 15), some H2 lines show a redshifted peak and a blueshifted low-level emission, which makes them asymmetric. Ignoring these stars, the four H2 lines are centered at the stellar rest velocity, with a standard deviations of 7.1, 6.5, 6.1, and 12.1 km s−1, respectively. The large scatter in the P(5)(4–11) line measurement is partly the result of low signal-to-noise in this region of the spectrum. Unlike the results reported by Linsky et al. (2012), we do not observe a systematic increase in the line center as a function of wavelength, neither star by star nor in the average of all stars for a given line. This is likely the result of the different acquisition procedure followed here. For the STIS data, the average standard deviation in all the H2 wavelengths is 4.4 km s−1.

This shows that the errors in the COS wavelength scale are smaller than the 15 km s−1 reported in the manuals and that no systematic shifts with wavelength are present. For the rest of the paper we will assume that the pointing errors in the COS data result in a velocity uncertainty of ±7 km s−1 (the average of the first three H2 lines considered) while the STIS errors are 5 km s−1. We do not correct the spectra for the H2 velocities, as it is not clear how to implement this correction in the case of stars with asymmetric H2 lines.

3. INTRODUCTION TO THE SHAPE OF THE LINES

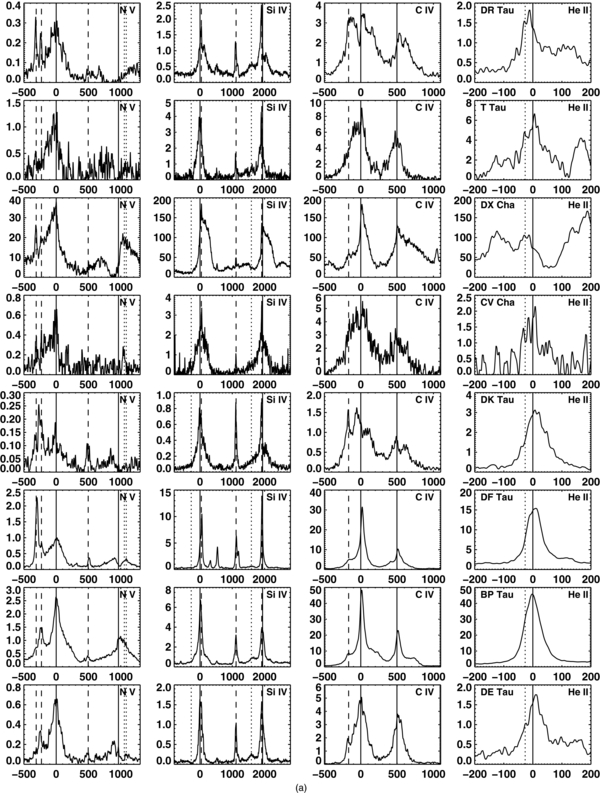

Figures 14 and 15 in the Appendix show the lines that we are discussing in this paper. Each line is plotted in velocity space (km s−1) centered on the stellar photospheric rest frame. The ordinate gives flux density in units 10−14 erg s−1 cm−2 Å−1. In the case of doublets, the nominal wavelength of the strongest member of the line is set to zero velocity, and the positions of the strongest H2 lines are marked with dashed lines. Dotted lines mark the positions of other features in the spectra. The plotted spectra have been smoothed by a five-point median.

The C iv, Si iv, and N v lines are resonance doublets with slightly offset upper levels. For each doublet, both lines should have the same shape when emitted. This redundancy allow us to identify extra spectral features and to distinguish real features from noise. If the lines are emitted from an optically thin or effectively thin plasma, their flux ratio should be 2:1. If the lines are emitted from a medium that has a thermalization depth smaller than its optical depth (i.e., the medium is optically thick, but not effectively thin) the flux ratio will tend to 1.

For a plasma at rest in coronal ionization equilibrium, the peak ion abundance occurs at temperatures of log (T) = 5.3 (K) for N v, log (T) = 5.0 (K) for C iv, log (T) = 4.9 (K) for Si iv, and log (T) = 4.7 (K) for He ii (Mazzotta et al. 1998). In the context of the magnetospheric accretion paradigm, the velocities of the post-shock gas are high enough that the collisional timescales are longer than the dynamical timescale (Ardila 2007). This implies that the post-shock gas lines may trace lower temperature, higher density plasma than in the coronal ionization equilibrium case. The pre-shock plasma is radiatively ionized to temperatures of ∼104 K. If the pre- and post-shock regions both contribute to the emission, conclusions derived from the usual differential emission analyses are not valid (e.g., Brooks et al. 2001). In the case of non-accreting stars, the resonance N v, C iv, and Si iv lines are collisionally excited while the He ii line is populated by radiative recombination in the X-ray ionized plasma (Zirin 1975).

Figure 1 compares the hot gas lines of BP Tau and the WTTS V396 Aur. These stars provide examples of the main observational points we will make in this paper.

- 1.For N v and C iv the lines of the CTTSs have broad wings not present in the WTTSs. This is generally also the case for Si iv, although for BP Tau the lines are weak compared to H2.

- 2.The N v 1243 Å line of BP Tau (the redder member of the multiplet), and of CTTSs in general, looks truncated when compared to the 1239 Å line (the blue member), in the sense of not having a sharp emission component. This is the result of N i circumstellar absorption.

- 3.The Si iv lines in CTTSs are strongly affected by H2 lines and weakly affected by CO A-X absorption bands (France et al. 2011; Schindhelm et al. 2012) and O iv. At the wavelengths of the Si iv lines, the dominant emission seen in BP Tau and other CTTSs is primarily due to fluorescent H2 lines. The WTTS do not show H2 lines or CO bands within ±400 km s−1 of the gas lines we study here.

- 4.The C iv BP Tau lines have similar shapes to each other, to the 1239 N v line, and to the Si iv lines, when observed. Generally, the CTTS C iv lines are asymmetric to the red and slightly redshifted with respect to the WTTS line.

- 5.The He ii lines are similar (in shape, width, and velocity centroid) in WTTSs and CTTSs, and similar to the narrow component (NC) of C iv.

The general statements above belie the remarkable diversity of line profiles in this sample. Some of this diversity is showcased in Figure 2. For analysis and interpretation, we focus on the C iv doublet lines, as they are the brightest and "cleanest" of the set, with the others playing a supporting role. In order to test the predictions of the magnetospheric accretion model, in Section 5.3 we perform a Gaussian decomposition of the C iv profiles, and representative results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Comparison between the CTTS BP Tau (black line) and the WTTS V396 Aur (blue line) for the four emission lines we are analyzing. The vertical scale is arbitrary. The abscissas are velocities (km s−1) in the stellar rest frame. Solid lines: nominal line positions; dashed lines: nominal locations of the strongest H2 lines. N v, dotted lines: N i (1243.18 Å, +1055 km s−1; 1243.31 Å, +1085 km s−1). Si iv, dotted lines: CO A-X (5–0) bandhead (1392.5 Å, −271 km s−1), O iv (1401.17 Å, +1633 km s−1). He ii, dotted line: location of the secondary He ii line.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 2. The diversity of C iv CTTSs profiles. Dashed lines: narrow and broad Gaussian components; smooth solid lines: total model fit. The most common morphology is that of TW Hya, with a lower peak BC redshifted with respect to the NC. Stars like IP Tau have a BC blueshifted with respect to the NC. For V1190 Sco, both components have similar widths. For HN Tau the NC profile is blueshifted.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTW Hya has a profile and decomposition similar to those of BP Tau: strong NC plus a redshifted, lower-peak broad component (BC). Of the stars for which a Gaussian decomposition is possible, ∼50% (12/22) show this kind of profile and ∼70% (21/29) of CTTSs in our sample have redshifted C iv peaks. HN Tau also has a NC plus a redshifted BC, but the former is blueshifted with respect to the stellar rest velocity by 80 km s−1. For IP Tau and V1190 Sco, the BC is blueshifted with respect to the NC. The magnetospheric accretion model may explain some of objects with morphologies analogous to TW Hya but blueshifted emission requires extensions to the model or the contributions of other emitting regions besides the accretion funnel (Günther & Schmitt 2008).

Figure 3 shows the C iv and He ii lines in all the WTTSs, scaled to the blue wings of the lines. For all except for V1068 Tau (Lk Ca 4) and V410 Tau, the C iv and He ii lines appear very similar to each other in shape, width, and shift. They are all fairly symmetric, with velocity maxima within ∼20 km s−1 of zero, and FWHM from 60 to 100 km s−1. V1068 Tau and V410 Tau have the largest FWHM in both C iv and He ii. The lines of these two stars appear either truncated or broadened with respect to the rest of the WTTSs. In the case of V410 Tau, vsin i = 73 km s−1 (Głe¸bocki & Gnaciński 2005), which means that rotational broadening is responsible for a significant fraction of the width. However, V1068 Tau has vsin i = 26 km s−1. For the rest of the WTTSs, vsin i ranges from 4 to 20 km s−1 (Głe¸bocki & Gnaciński 2005; Torres et al. 2006).

Figure 3. The WTTSs spectra in C iv and He ii. All the spectra have been scaled to have the same mean value in the wing between −150 and −50 km s−1. The solid vertical lines mark the rest-velocity positions of the C iv and He ii lines. Top: C iv. The dashed vertical line indicates the location at which the H2 line R(3)1–8 would be, if present. The large value of the TWA 7 line is an artifact of the scaling procedure, due to the line redshift (25.3 km s−1). Bottom: He ii. Except for V1068 Tau and V410 Tau, the WTTSs have similar characteristics (shape, shifts, and FWHM) in He ii and C iv. V1068 Tau and V410 Tau appear to be truncated or broadened in both lines.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTo characterize the line shapes of He ii and C iv we have defined non-parametric and parametric shape measurements. The non-parametric measurements (Table 5) do not make strong assumptions about the line shapes and they provide a intuitive summary description of the line. These are the velocity at maximum flux, the FWHM, and the skewness, defined in Section 5.2. For C iv we have also measured the ratio of the 1548 Å to the 1550 Å line, by scaling the line wings to match each other. This provides a measure of the line optical depth. The parametric measurements (Tables 6 and 7) assume that each C iv and He ii line is a combination of two Gaussians.

Table 5. Non-parametric Line Measurements

| Name | C iv | He ii | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio Blue/Red a | FWHM b | Vel. at max. flux c | Skewness d | FWHM e | Vel. at max. flux | Skewness f | |

| (km s−1) | (km s−1) | (km s−1) | (km s−1) | ||||

| Classical T Tauri Stars | |||||||

| AA Tau | 1.28 ± 0.1 | 207.4 | 32.2 ± 1 | 0.09 | 87.6 | 23.7 ± 1 | 0.01 |

| AK Sco | 1.89 ± 0.2 | 116.4 | −27.2 ± 2 | −0.06 | ... | ... | ... |

| BP Tau | 1.92 ± 0.1 | 82.9 | 14.1 ± 1 | 0.04 | 65.7 | −1.2 ± 1 | 0.01 |

| CV Cha | 2.15 ± 0.2 | 196.7 | −3.9 ± 6 | 0.01 | 53.7 | 5.7 ± 1 | 0.00 |

| CY Tau | 1.69 ± 0.3 | 45.5 | 19.6 ± 2 | 0.12 | 43.8 | −0.6 ± 2 | 0.02 |

| DE Tau | 1.38 ± 0.1 | 141.8 | 6.6 ± 2 | 0.00 | 81.6 | 9.0 ± 1 | 0.02 |

| DF Tau | 2.89 ± 0.1 | 96.3 | 17.5 ± 1 | −0.03 | 64.7 | 6.8 ± 1 | 0.01 |

| DK Tau | 1.79 ± 0.1 | 262.2 | −31.5 ± 1 | 0.05 | 83.6 | 8.3 ± 1 | 0.02 |

| DN Tau | 1.82 ± 0.1 | 74.9 | 19.0 ± 1 | 0.05 | 69.7 | −3.3 ± 1 | 0.01 |

| DR Tau | 1.52 ± 0.1 | 236.8 | 33.7 ± 1 | 0.07 | 66.7 | −12.4 ± 1 | 0.05 |

| DS Tau | 2.11 ± 0.1 | 61.5 | 15.5 ± 1 | 0.06 | 55.7 | 0.1 ± 2 | 0.01 |

| DX Cha | 1.24 ± 0.1 | 374.6 | 11.5 ± 1 | 0.07 | ... | ... | ... |

| EP Cha | 1.66 ± 0.1 | 153.8 | 21.2 ± 1 | 0.03 | 79.6 | −0.2 ± 1 | 0.01 |

| ET Cha | 1.24 ± 0.1 | 260.9 | −5.0 ± 1 | 0.03 | 80.6 | 6.1 ± 1 | −0.01 |

| HN Tau A | 1.67 ± 0.1 | 310.4 | −84.5 ± 1 | 0.05 | 226.9 | −82.9 ± 3 | 0.01 |

| MP Mus | 1.97 ± 0.2 | 267.6 | 9.8 ± 1 | −0.04 | 78.6 | −4.6 ± 2 | 0.02 |

| RU Lup | 1.26 ± 0.2 | 148.5 | 31.6 ± 2 | −0.05 | 90.5 | 19.6 ± 2 | 0.01 |

| RW Aur A | 1.45 ± 0.1 | 387.0 | −86.4 ± 1 | −0.021 | 131.7 | −99.2 ± 2 | 0.02 |

| SU Aur | 1.38 ± 0.1 | 335.8 | 44.3 ± 2 | −0.02 | 120.4 | 35.1 ± 1 | 0.00 |

| T Tau N | 1.71 ± 0.2 | 169.9 | −4.2 ± 1 | −0.07 | 79.5 | 4.9 ± 1 | −0.01 |

| V1190 Sco | 1.58 ± 0.2 | 251.5 | −2.7 ± 2 | −0.05 | 210.9 | 7.6 ± 2 | −0.05 |

| V4046 Sgr | 2.00 ± 0.1 | 301.0 | 55.3 ± 1 | 0.06 | 180.1 | 42.4 ± 1 | 0.00 |

| Transition Disks | |||||||

| CS Cha | 1.69 ± 0.1 | 235.8 | 32.0 ± 1 | 0.09 | 134.5 | 11.3 ± 1 | 0.01 |

| DM Tau | 1.72 ± 0.1 | 297.0 | 62.4 ± 1 | 0.06 | 75.6 | 7.5 ± 1 | 0.02 |

| GM Aur | 1.83 ± 0.1 | 270.2 | 26.0 ± 1 | −0.05 | 127.4 | −3.3 ± 1 | 0.02 |

| IP Tau | 1.27 ± 0.1 | 66.9 | 12.9 ± 1 | −0.06 | 87.6 | 8.0 ± 2 | 0.02 |

| TW Hya | 1.85 ± 0.1 | 247.5 | 26.4 ± 2 | 0.13 | 64.7 | 3.5 ± 1 | 0.04 |

| UX Tau A | 1.78 ± 0.1 | 290.8 | 1.3 ± 3 | −0.02 | 83.4 | −10.5 ± 1 | 0.03 |

| V1079 Tau | 1.89 ± 0.1 | 171.2 | 30.1 ± 1 | −0.01 | 68.7 | 14.9 ± 1 | 0.04 |

| Weak T Tauri Stars | |||||||

| EG Cha | 1.72 ± 0.1 | 88.3 | 9.5 ± 1 | 0.01 | 67.7 | −5.7 ± 1 | −0.01 |

| TWA 7 | 2.03 ± 0.1 | 59.4 | 12.3 ± 1 | 0.01 | 58.4 | −0.3 ± 1 | 0.00 |

| V1068 Tau | 1.74 ± 0.1 | 115.1 | 15.9 ± 1 | −0.02 | 96.5 | 11.6 ± 1 | −0.02 |

| V396 Aur | 2.14 ± 0.1 | 77.6 | 3.1 ± 1 | 0.00 | 74.6 | −12.6 ± 1 | 0.04 |

| V397 Aur | 1.91 ± 0.1 | 69.6 | −2.4 ± 1 | 0.01 | 77.6 | 18.0 ± 1 | −0.02 |

| V410 Tau | 2.15 ± 0.7 | 145.5 | 25.3 ± 7 | −0.01 | 136.3 | 13.7 ± 1 | −0.05 |

Notes. All velocities are calculated on the stellar rest frame. aThe ratio of the two C iv lines is calculated by matching the red wings of both lines between 0 and 150 km s−1. For RW Aur A, the scaling is calculated from 0 to 100 km s−1 only. bThis is the FWHM of the red C iv line. The error is ±5 km s−1. cVelocity at maximum flux for the C iv profile. Except for RW Aur A, this is the average of the two doublet lines. For RW Aur A it is only the velocity of the red line. dSkewness of the C iv profile, averaged over the two lines. For each line, skewness is defined as  , where

, where  is the flux-weighted mean velocity over an interval ΔV. For the blue and red lines, the intervals are ±250 km s−1 and ±150 km s−1 from the maximum, respectively. To calculate the average, we normalize the red C iv skewness to the blue one, by dividing by 250/150. To calculate the skewness, we have subtracted the continuum and interpolated over the H2 lines. Values of the skewness within ∼[−0.02, 0.02] indicate a symmetric line. eFWHM of the He ii line. The error is ±5 km s−1. fSkewness of the He ii profile. Measured over ±100 km s−1, but normalized to the C iv interval.

is the flux-weighted mean velocity over an interval ΔV. For the blue and red lines, the intervals are ±250 km s−1 and ±150 km s−1 from the maximum, respectively. To calculate the average, we normalize the red C iv skewness to the blue one, by dividing by 250/150. To calculate the skewness, we have subtracted the continuum and interpolated over the H2 lines. Values of the skewness within ∼[−0.02, 0.02] indicate a symmetric line. eFWHM of the He ii line. The error is ±5 km s−1. fSkewness of the He ii profile. Measured over ±100 km s−1, but normalized to the C iv interval.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

Table 6. Gaussian Fits to the C iv Lines

| Blue Line | Red Line | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow Comp. | Broad Comp. | Narrow Comp. | Broad Comp. | |||||||||||||

| Name a | A0 | ΔA0 | V0 | ΔV0 | σ0 | Δσ0 | A1 | ΔA1 | V1 | ΔV1 | σ1 | Δσ1 | A2 | ΔA2 | A3 | ΔA3 |

| Flux | Flux | (km s−1) | (km s−1) | (km s−1) | (km s−1) | Flux | Flux | (km s−1) | (km s−1) | (km s−1) | (km s−1) | Flux | Flux | Flux | Flux | |

| Classical T Tauri Stars | ||||||||||||||||

| AA Tau (COS) | 2.81 | 0.1 | 23.65 | 0.3 | 17.50 | 0.2 | 2.70 | 0.1 | 82.86 | 0.4 | 120.94 | 0.5 | 2.78 | 0.1 | 1.37 | 0.1 |

| AK Sco (STIS) | 9.56 | 0.1 | −78.18 | 0.2 | 115.08 | 0.3 | 3.69 | 0.1 | −11.05 | 0.1 | 257.8 | 1 | 2.67 | 0.1 | 2.46 | 0.1 |

| BP Tau (COS) | 32.28 | 0.2 | 14.49 | 0.1 | 24.91 | 0.1 | 13.99 | 0.1 | 45.11 | 0.1 | 151.00 | 0.2 | 16.12 | 0.2 | 6.19 | 0.1 |

| BP Tau (GHRS) | 10.2 | 2 | 9.3 | 1 | 33.5 | 3 | 6.85 | 0.4 | −12.5 | 1 | 123.6 | 2 | 4.4 | 1 | 2.94 | 0.2 |

| CV Cha (STIS) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | 4.43 | 0.2 | −4.77 | 0.1 | 140.04 | 0.3 | ... | ... | 2.16 | 0.1 |

| CY Tau (STIS) | 7.35 | 0.5 | 20.85 | 0.7 | 20.43 | 0.8 | 2.24 | 0.1 | 104.48 | 3.3 | 126.46 | 3.4 | 4.19 | 0.4 | 1.10 | 0.1 |

| DE Tau (COS) | 3.12 | 0.4 | 21.0 | 1 | 54.7 | 2 | 1.37 | 0.2 | 23.6 | 2 | 129.7 | 5 | 2.69 | 0.3 | 0.76 | 0.2 |

| DF Tau (COS) | 20.45 | 0.2 | 23.00 | 0.1 | 23.81 | 0.1 | 7.74 | 0.1 | −3.96 | 0.1 | 112.93 | 0.2 | 5.06 | 0.1 | 4.18 | 0.1 |

| DF Tau (GHRS) | 48.7 | 2 | 34.0 | 1 | 36.1 | 1 | 5.2 | 1 | −7.96 | 0.4 | 133.6 | 1 | 17.2 | 1 | 2.56 | 0.1 |

| DF Tau (STIS) | 49.0 | 2 | 26.54 | 0.4 | 19.65 | 0.3 | 7.43 | 0.3 | 26.0 | 1 | 104.3 | 2 | 14.5 | 1 | 3.52 | 0.2 |

| DK Tau (COS) | 0.45 | 0.1 | −20.7 | 8 | 25.3 | 8 | 0.93 | 0.1 | 36.4 | 3 | 142.5 | 6 | 0.23 | 0.1 | 0.49 | 0.1 |

| DN Tau (COS) | 10.86 | 0.1 | 21.33 | 0.1 | 28.87 | 0.2 | 2.92 | 0.1 | 63.76 | 0.4 | 120.79 | 0.5 | 6.22 | 0.1 | 1.26 | 0.1 |

| DR Tau (COS) | 1.55 | 0.3 | 80.7 | 4 | 80.2 | 4 | 1.02 | 0.2 | 98.4 | 6 | 197.2 | 9 | 1.38 | 0.2 | 0.35 | 0.1 |

| DR Tau (STIS) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | 1.28 | 0.2 | 226.3 | 7 | 58.3 | 4 | ... | ... | 0.70 | 0.1 |

| DR Tau (GHRS 1995) | 1.7 | 1 | 112.2 | 7 | 50.8 | 4 | 1.54 | 0.4 | 17.1 | 2 | 76.4 | 5 | 2.5 | 1 | <0.2 | ... |

| DS Tau (STIS) | 38.9 | 1 | 27.61 | 0.2 | 23.34 | 0.3 | 5.71 | 0.2 | 57.3 | 1 | 147.4 | 2 | 23.5 | 1 | 2.32 | 0.1 |

| DX Cha b (STIS) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| EP Cha (COS) | 3.84 | 0.1 | 28.94 | 0.3 | 30.25 | 0.3 | 5.20 | 0.1 | 40.17 | 0.2 | 136.23 | 0.3 | 2.31 | 0.1 | 2.74 | 0.1 |

| ET Cha (COS) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | 1.58 | 0.1 | 9.76 | 0.2 | 99.80 | 0.4 | ... | ... | 0.98 | 0.1 |

| HN Tau A (COS) | 1.60 | 0.1 | −80.42 | 0.5 | 84.48 | 0.6 | 0.51 | 0.1 | 179.0 | 2 | 104.0 | 2 | 0.84 | 0.1 | 0.38 | 0.1 |

| MP Mus (STIS) | 18.49 | 0.1 | −4.47 | 0.1 | 74.92 | 0.1 | 22.63 | 0.1 | 6.06 | 0.1 | 153.34 | 0.1 | 12.96 | 0.1 | 10.16 | 0.1 |

| RU Lup (COS) | 12.09 | 0.1 | 36.63 | 0.1 | 43.36 | 0.1 | 6.77 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 192.95 | 0.1 | 11.07 | 0.1 | 3.85 | 0.1 |

| RU Lup (STIS) | 20 | 0.5 | 10.22 | 0.2 | 35.00 | 0.4 | 7.98 | 0.2 | −0.08 | 0 | 184.5 | 2 | 14.85 | 0.4 | 3.86 | 0.1 |

| RU Lup (GHRS) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | 5.5 | 1 | −15 | 15 | 100.5 | 5 | ... | ... | 4.5 | 1 |

| RW Aur b (COS) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| SU Aur (COS) | 1.00 | 0.3 | 85.2 | 7 | 113.2 | 9 | 1.88 | 0.3 | 17.0 | 1 | 160.3 | 5 | 1.03 | 0.3 | 1.02 | 0.3 |

| T Tau N (STIS) | 3.31 | 0.5 | −22.2 | 1 | 75.2 | 2 | 3.91 | 0.3 | −56.3 | 2 | 144.1 | 3 | 4.71 | 0.3 | <0.1 | ... |

| T Tau N (GHRS) | 6 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.2 | 79 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 0.1 | −52 | 1.2 | 152 | 0.7 | 5.3 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.1 |

| V1190 Sco (COS) | 3.55 | 0.1 | 9.44 | 0.1 | 83.97 | 0.1 | 1.50 | 0.1 | −103.54 | 0.1 | 104.13 | 0.1 | 2.24 | 0.1 | 1.00 | 0.1 |

| V4046 Sgr (COS) | 11.2 | 1 | 60.4 | 2 | 54.2 | 2 | 13.69 | 0.5 | 117.6 | 1 | 164.9 | 2 | 4.45 | 0.7 | 7.47 | 0.4 |

| Transition Disks | ||||||||||||||||

| CS Cha (COS) | 1.86 | 0.3 | 60 | 4 | 78.8 | 5 | 1.83 | 0.2 | 208.7 | 6 | 183.9 | 7 | 0.68 | 0.2 | 1.02 | 0.2 |

| DM Tau (COS) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | 3.11 | 0.1 | 81.54 | 0.1 | 131.73 | 0.1 | ... | ... | 1.78 | 0.1 |

| GM Aur (COS) | 4.93 | 0.2 | 23.34 | 0.5 | 30.23 | 0.7 | 8.86 | 0.1 | 1.17 | 0.1 | 141.68 | 0.4 | 1.97 | 0.2 | 4.84 | 0.1 |

| IP Tau (COS) | 1.20 | 0.1 | 19.75 | 0.4 | 28.28 | 0.6 | 0.93 | 0.1 | −20.62 | 0.3 | 129.67 | 0.8 | 0.72 | 0.1 | 0.63 | 0.1 |

| TW Hya (STIS) | 122.93 | 2.2 | 27.74 | 0.3 | 35.32 | 0.3 | 133.68 | 0.9 | 116.58 | 0.3 | 142.43 | 0.3 | 55.02 | 1.5 | 73.64 | 0.6 |

| UX Tau A (COS) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | 2.44 | 0.1 | 18.5 | 0.3 | 135.5 | 1 | ... | ... | 1.22 | 0.1 |

| V1079 Tau (COS) | 2.35 | 0.5 | 21.3 | 2 | 40.6 | 3 | 2.67 | 0.2 | 50.9 | 2 | 149.9 | 3 | 1.13 | 0.3 | 1.34 | 0.1 |

| Weak T Tauri Stars | ||||||||||||||||

| EG Cha (COS) | 2.91 | 0.1 | 4.16 | 0.1 | 33.41 | 0.1 | 1.03 | 0.1 | 1.42 | 0.2 | 104.19 | 0.1 | 1.75 | 0.1 | 0.53 | 0.1 |

| TWA 7 (COS) | 4.05 | 0.2 | 16.44 | 0.3 | 19.25 | 0.4 | 2.17 | 0.1 | 17.03 | 0.3 | 53.40 | 0.5 | 2.37 | 0.1 | 0.98 | 0.1 |

| V1068 Tau (COS) | 0.7 | 0.2 | −4.28 | 1 | 54.9 | 5 | 0.22 | 0.1 | 68.7 | 10 | 130.8 | 12 | 0.41 | 0.1 | 0.111 | 0.05 |

| V396 Aur (COS) | 2.06 | 0.7 | −4.03 | 1.5 | 29.10 | 4.2 | 0.44 | 0.1 | 7.57 | 0.4 | 101.82 | 1.2 | 1.07 | 0.5 | 0.24 | 0.1 |

| V397 Aur (COS) | 0.54 | 0.1 | −1.41 | 0.1 | 23.28 | 0.1 | 0.44 | 0.1 | −3.07 | 0.1 | 64.10 | 0.1 | 0.35 | 0.1 | 0.22 | 0.1 |

| V410 Tau (STIS) | 1.42 | 0.1 | −0.04 | 1.0 | 66.51 | 2.7 | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | 0.76 | 0.1 | ... | ... |

Notes. The flux has been fit in units of 10−14 erg s−1 cm−2. For each complex of two C iv lines we fit either two or four Gaussians. In the case of two Gaussians:  . In the case of four Gaussians:

. In the case of four Gaussians:  . aThe instrument used to obtain the data is indicated in parentheses. bFor DX Cha and RW Aur the red wing of the red line is different than the red wing of the blue line and neither a four nor an eight parameter fit is possible.

. aThe instrument used to obtain the data is indicated in parentheses. bFor DX Cha and RW Aur the red wing of the red line is different than the red wing of the blue line and neither a four nor an eight parameter fit is possible.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset images: Typeset image Typeset image

Table 7. He ii Gaussian Fits

| Name a | A0 | V0 | σ0 | A1 | V1 | σ1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (10−14 erg s−1 cm−2) | (km s−1) | (km s−1) | (10−14 erg s−1 cm−2) | (km s−1) | (km s−1) | |

| Classical T Tauri Stars | ||||||

| AA Tau (COS) | 5.20 ± 0.1 | 25.54 ± 0.2 | 36.17 ± 0.3 | 0.47 ± 0.1 | 127.0 ± 3 | 219.2 ± 3 |

| AK Sco (STIS) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| BP Tau (COS) | 38.75 ± 0.2 | 2.89 ± 0.1 | 29.76 ± 0.1 | 2.31 ± 0.1 | −2.13 ± 0.2 | 195.2 ± 1 |

| CV Cha (STIS) | 1.24 ± 0.2 | 10.5 ± 2.0 | 44.28 ± 3.8 | ... | ... | ... |

| CY Tau (STIS) | 6.72 ± 0.8 | 3.36 ± 0.6 | 21.37 ± 1.0 | 1.01 ± 0.4 | 15.0 ± 4 | 54.1 ± 8 |

| DE Tau (COS) | 1.24 ± 0.1 | 5.92 ± 0.1 | 25.28 ± 0.1 | 0.31 ± 0.1 | 21.18 ± 0.6 | 170.4 ± 2 |

| DF Tau (COS) | 12.62 ± 0.1 | 6.88 ± 0.1 | 24.71 ± 0.2 | 2.21 ± 0.1 | 36.14 ± 0.4 | 141.49 ± 0.8 |

| DK Tau (COS) | 2.92 ± 0.1 | 11.38 ± 0.4 | 32.43 ± 0.5 | 0.15 ± 0.1 | 44.20 ± 0.1 | 191.23 ± 0.4 |

| DN Tau (COS) | 13.18 ± 0.2 | −0.04 ± 0.1 | 31.38 ± 0.2 | 0.98 ± 0.1 | 72.5 ± 1 | 129.3 ± 2 |

| DR Tau (COS) | 1.22 ± 0.1 | −14.42 ± 0.5 | 28.66 ± 0.7 | 0.62 ± 0.1 | 104.9 ± 3 | 48.4 ± 2 |

| DS Tau (STIS) | 20.43 ± 0.7 | −1.53 ± 0.4 | 25.64 ± 0.4 | 3.83 ± 0.3 | 325.2 ± 3 | 33.6 ± 1 |

| DX Cha (STIS) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| EP Cha (COS) | 6.92 ± 0.1 | −5.79 ± 0.2 | 28.79 ± 0.2 | 1.86 ± 0.1 | 25.74 ± 0.2 | 98.38 ± 0.4 |

| ET Cha (COS) | 1.51 ± 0.1 | −2.38 ± 0.1 | 20.47 ± 0.9 | 1.51 ± 0.1 | 1.15 ± 0.1 | 68.22 ± 0.7 |

| HN Tau A (COS) | 0.33 ± 0.1 | −89.34 ± 1.0 | 57.80 ± 0.8 | 0.23 ± 0.1 | 0.16 ± 0.1 | 204.1 ± 2 |

| MP Mus (STIS) | 17.80 ± 0.1 | −0.57 ± 0.1 | 25.15 ± 0.1 | 6.49 ± 0.1 | 6.83 ± 0.2 | 107.86 ± 0.4 |

| RU Lup (COS) | 7.27 ± 0.1 | 20.58 ± 0.1 | 35.78 ± 0.1 | ... | ... | ... |

| RW Aur (COS) | 0.78 ± 0.1 | −96.6 ± 3 | 27.2 ± 2 | 0.48 ± 0.1 | −48.5 ± 4 | 91.8 ± 5 |

| SU Aur (COS) | 2.26 ± 0.1 | 28.44 ± 0.1 | 43.37 ± 0.1 | 0.44 ± 0.1 | −0.15 ± 0.1 | 197.74 ± 0.9 |

| T Tau N (STIS) | 3.53 ± 0.3 | 0.14 ± 0.1 | 47.1 ± 2 | 0.79 ± 0.2 | 0.49 ± 0.1 | 146.5 ± 5 |

| V1190 Sco (COS) | 1.28 ± 0.1 | −23.37 ± 0.1 | 88.85 ± 0.1 | ... | ... | ... |

| V4046 Sgr (COS) | 19.24 ± 0.2 | 35.25 ± 0.2 | 66.85 ± 0.2 | 11.01 ± 0.2 | 58.01 ± 0.2 | 120.43 ± 0.4 |

| Transition Disks | ||||||

| CS Cha (COS) | 8.12 ± 0.1 | 17.53 ± 0.2 | 53.03 ± 0.3 | 1.03 ± 0.1 | 170.9 ± 3 | 191.6 ± 3 |

| DM Tau (COS) | 8.00 ± 0.1 | 7.74 ± 0.1 | 31.09 ± 0.2 | 1.65 ± 0.1 | 76.10 ± 0.9 | 132.79 ± 0.5 |

| GM Aur (COS) | 6.29 ± 0.1 | −5.24 ± 0.3 | 42.39 ± 0.5 | 1.78 ± 0.1 | 8.95 ± 0.8 | 209.0 ± 1 |

| IP Tau (COS) | 2.73 ± 0.1 | 11.46 ± 0.3 | 31.97 ± 0.3 | 0.15 ± 0.1 | 1.46 ± 0.1 | 163.50 ± 0.3 |

| TW Hya (STIS) | 292.00 ± 4.0 | −0.16 ± 0.1 | 21.99 ± 0.1 | 78.00 ± 2.1 | 49.18 ± 0.6 | 34.25 ± 0.5 |

| UX Tau A (COS) | 3.55 ± 0.2 | −0.25 ± 0.1 | 35.5 ± 1 | 0.65 ± 0.1 | 15.5 ± 2 | 150.4 ± 5 |

| V1079 Tau (COS) | 2.12 ± 0.1 | 16.00 ± 0.1 | 24.37 ± 0.1 | 0.67 ± 0.1 | 73.24 ± 0.4 | 44.27 ± 0.5 |

| Weak T Tauri Stars | ||||||

| EG Cha (W) (COS) | 6.31 ± 0.1 | −7.75 ± 0.1 | 27.70 ± 0.1 | 0.90 ± 0.1 | −4.98 ± 0.1 | 88.27 ± 0.1 |

| TWA 7 (COS) | 8.30 ± 0.3 | 0.15 ± 0.1 | 21.66 ± 0.3 | 1.85 ± 0.1 | 0.15 ± 0.1 | 55.1 ± 1 |

| V1068 Tau (W) (COS) | 0.94 ± 0.1 | 6.30 ± 0.1 | 48.15 ± 0.1 | ... | ... | ... |

| V396 Aur (W) (COS) | 2.56 ± 0.1 | −0.09 ± 0.1 | 33.88 ± 0.2 | 0.32 ± 0.1 | −1.75 ± 0.1 | 83.73 ± 0.2 |

| V397 Aur (W) (COS) | 1.37 ± 0.1 | 13.42 ± 0.1 | 33.80 ± 0.1 | ... | ... | ... |

| V410 Tau (W) (STIS) | 2.64 ± 0.2 | 11.3 ± 1 | 46.22 ± 2.0 | ... | ... | ... |

Notes. The He ii region of AK Sco is too noisy to allow the Gaussian fit. DX Cha does not show a single clear emission line in the spectral region. aWTTSs are indicated with a (W) after their name; the instrument used to obtain the data is indicated in parentheses.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

Table 8 lists the flux measurements that we will be considering in the following sections. The fluxes are obtained by direct integration of the spectra over the spectral range listed in the table, after subtracting the continuum and interpolating over known blending features (see Section 5).

Table 8. Hot Line Fluxes, Not Corrected for Extinction

| Name | N v (1238.8 Å) | N v (1242.8 Å) | Si iv (1393.8 Å) a | Si iv (1402.8 Å) a | C iv (1548.2 + 1550.8 Å) b | He ii (1640.5 Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (10−14 erg s−1 cm−2) | (10−14 erg s−1 cm−2) | (10−14 erg s−1 cm−2) | (10−14 erg s−1 cm−2) | (10−14 erg s−1 cm−2) | (10−14 erg s−1 cm−2) | |

| Classical T Tauri Stars | ||||||

| AA Tau | 0.221 ± 0.01 | 0.150 ± 0.01 | <0.3 | <0.3 | 8.66 ± 0.1 | 3.94 ± 0.1 |

| AK Sco | 2.43 ± 0.2 | 1.37 ± 0.2 | 10.2 ± 3 | 11.0 ± 3 | 37.6 ± 1 | <1 |

| BP Tau | 2.186 ± 0.02 | 0.984 ± 0.02 | 4.76 ± 0.3 | 3.34 ± 0.3 | 55.47 ± 0.1 | 23.20 ± 0.2 |

| CV Cha | 0.63 ± 0.1 | 0.09 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 1 | 3.6 ± 1 | 12.28 ± 0.1 | 1.78 ± 0.6 |

| CY Tau | 1.20 ± 0.1 | <0.3 | <4 | <4 | 9.10 ± 0.3 | 4.12 ± 0.9 |

| DE Tau | 0.475 ± 0.01 | 0.084 ± 0.01 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 8.68 ± 0.1 | 1.31 ± 0.2 |

| DF Tau | 1.080 ± 0.02 | 0.314 ± 0.02 | <0.9 | <0.8 | 25.69 ± 0.1 | 9.26 ± 0.2 |

| DK Tau | 0.145 ± 0.01 | 0.015 ± 0.01 | 0.68 ± 0.1 | 0.55 ± 0.1 | 3.503 ± 0.05 | 1.78 ± 0.2 |

| DN Tau | 0.901 ± 0.01 | 0.400 ± 0.01 | 1.20 ± 0.2 | 0.072 ± 0.01 | 13.07 ± 0.1 | 7.51 ± 0.2 |

| DR Tau | 0.287 ± 0.01 | <0.03 | 1.46 ± 0.3 | 1.27 ± 0.3 | 8.71 ± 0.1 | 1.31 ± 0.3 |

| DS Tau | 0.84 ± 0.1 | 0.23 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 1 | 2.7 ± 1 | 35.93 ± 0.5 | 11.8 ± 1 |

| DX Cha | 35.92 ± 0.6 | 5.90 ± 0.6 | 218 ± 10 | 169 ± 10 | 147.1 ± 2 | N/A |

| EP Cha | 0.983 ± 0.01 | 0.399 ± 0.01 | 0.98 ± 0.1 | 0.62 ± 0.1 | 16.57 ± 0.7 | 5.62 ± 0.1 |

| ET Cha | 0.411 ± 0.01 | 0.254 ± 0.01 | <0.5 | <0.5 | 3.619 ± 0.03 | 2.10 ± 0.1 |

| HN Tau A | 0.2837 ± 0.007 | 0.1335 ± 0.007 | 1.90 ± 0.2 | 1.67 ± 0.2 | 4.132 ± 0.04 | 0.97 ± 0.1 |

| MP Mus | 5.68 ± 0.1 | 2.49 ± 0.1 | 8.6 ± 1 | 4.9 ± 1 | 94.3 ± 1 | 17.30 ± 1.0 |

| RU Lup | 2.574 ± 0.05 | 0.308 ± 0.05 | 25.9 ± 1 | 18.8 ± 1 | 44.8 ± 1 | 5.79 ± 0.5 |

| RW Aur A | 0.812 ± 0.02 | 0.038 ± 0.01 | 4.68 ± 0.4 | 4.66 ± 0.4 | 6.00 ± 0.1 c | 1.85 ± 0.3 |

| SU Aur | 0.463 ± 0.01 | 0.202 ± 0.01 | 1.26 ± 0.2 | 1.54 ± 0.2 | 9.53 ± 0.1 | 2.59 ± 0.2 |

| T Tau N | 1.14 ± 0.1 | 0.55 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 1 | 2.8 ± 1 | 16.15 ± 0.1 | 5.89 ± 1.0 |

| V1190 Sco | 0.700 ± 0.01 | 0.354 ± 0.01 | <0.4 | <0.4 | 9.65 ± 0.1 | 1.63 ± 0.1 |

| V4046 Sgr | 29.66 ± 0.1 | 10.43 ± 0.1 | <1 | <1 | 57.10 ± 0.1 | 38.05 ± 0.2 |

| Transition Disks | ||||||

| CS Cha | 2.491 ± 0.03 | 0.848 ± 0.02 | <0.8 | <0.7 | 9.93 ± 0.1 | 9.01 ± 0.2 |

| DM Tau | 0.853 ± 0.02 | 0.281 ± 0.02 | <0.4 | <0.4 | 8.57 ± 0.1 | 7.11 ± 0.1 |

| GM Aur | 2.383 ± 0.03 | 0.662 ± 0.03 | <1 | <1 | 28.23 ± 0.2 | 8.50 ± 0.2 |

| IP Tau | 0.1211 ± 0.006 | 0.0491 ± 0.006 | 0.34 ± 0.1 | 0.31 ± 0.1 | 3.560 ± 0.04 | 1.64 ± 0.1 |

| TW Hya | 38.30 ± 0.6 | 17.13 ± 0.4 | 8.8 ± 3 | 7.6 ± 3 | 473.4 ± 2 | 228.9 ± 4 |

| UX Tau A | 0.949 ± 0.03 | 0.391 ± 0.01 | 1.08 ± 0.2 | 0.73 ± 0.2 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 2.80 ± 0.3 |

| V1079 Tau | 0.485 ± 0.01 | 0.136 ± 0.01 | 1.32 ± 0.2 | 1.11 ± 0.2 | 9.80 ± 0.1 | 1.78 ± 0.1 |

| Weak T Tauri Stars | ||||||

| EG Cha | 0.948 ± 0.01 | 0.460 ± 0.01 | 1.76 ± 0.1 | 1.08 ± 0.1 | 4.111 ± 0.05 | 3.50 ± 0.1 |

| TWA 7 | 0.759 ± 0.02 | 0.399 ± 0.01 | 1.03 ± 0.2 | 0.68 ± 0.2 | 3.925 ± 0.04 | 4.03 ± 0.1 |

| V1068 Tau | 0.0813 ± 0.004 | 0.0428 ± 0.004 | 0.116 ± 0.03 | 0.0064 ± 0.001 | 1.412 ± 0.03 | 0.69 ± 0.1 |

| V396 Aur | 0.2335 ± 0.008 | 0.1118 ± 0.008 | 0.52 ± 0.1 | 0.298 ± 0.07 | 2.357 ± 0.04 | 1.47 ± 0.1 |

| V397 Aur | 0.0895 ± 0.004 | 0.0455 ± 0.004 | 0.142 ± 0.04 | 0.082 ± 0.02 | 0.855 ± 0.02 | 0.75 ± 0.1 |

| V410 Tau | 0.30 ± 0.1 | <0.3 | <3 | <3 | 2.37 ± 0.2 | 2.51 ± 0.8 |

Notes. aMeasured fluxes not corrected for extinction. The fluxes were obtained by integrating between −400 km s−1 and 400 km s−1, except for EG Cha. For this star, the Si iv flux was obtained by integrating from −800 to 600 km s−1. bMeasured fluxes not corrected for extinction. The flux has been measured from −400 to 900 km s−1, interpolating over the R(3)1–8 H2 line. cThe C iv line flux for RW Aur A was obtained by creating a synthetic blue line, as a copy of the red C iv line but scaled by 1.4.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

4. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ACCRETION RATE AND C iv LUMINOSITY

As mentioned in the introduction, Johns-Krull et al. (2000) showed that the accretion rate is correlated with excess C iv luminosity. The excess C iv luminosity is obtained by subtracting the stellar atmosphere contribution to the observed line. They estimated the stellar contribution to be 6 × 10−5 L☉ for a 2 R☉ object. They also showed that the correlation of C iv excess luminosity with accretion rate is very sensitive to extinction estimates. More recently, Yang et al. (2012) obtain a linear correlation between the C iv luminosity (from STIS and ACS/SBC low-resolution spectra) and the accretion luminosity (from literature values) for 91 CTTSs. Here we show that our data are consistent with a correlation between accretion rate C iv luminosity and explore the role that the lack of simultaneous observations or different extinction estimates play in this relationship.

Figure 4 compares accretion rates (references given in Table 1) with the C iv line luminosities. Blue diamonds correspond to objects with simultaneous determinations of  and

and  when available (Ingleby et al. 2013) and green diamonds correspond to

when available (Ingleby et al. 2013) and green diamonds correspond to  determinations for the rest of the objects. Note that the accretion rate estimates from Ingleby et al. (2013) are derived using the extinction values from Furlan et al. (2009, 2011).

determinations for the rest of the objects. Note that the accretion rate estimates from Ingleby et al. (2013) are derived using the extinction values from Furlan et al. (2009, 2011).

Figure 4. Accretion rate vs. C iv luminosity. The blue diamonds correspond to stars with simultaneous determinations of accretion rate and line luminosity. The red diamonds are objects with non-simultaneous determinations of accretion rate. The solid line is the correlation obtained by using all of the diamonds. Black triangles use the extinctions from Furlan et al. (2009, 2011) to calculate  . Errors in

. Errors in  /L☉ are ∼5%–10%. The dashed line is Equation (2) from Johns-Krull et al. (2000), assuming R* = 2 R☉ for all stars. The lowest luminosity blue diamond corresponds to ET Cha (RECX 15) which has R* = 0.9 R☉ (Siess et al. 2000).

/L☉ are ∼5%–10%. The dashed line is Equation (2) from Johns-Krull et al. (2000), assuming R* = 2 R☉ for all stars. The lowest luminosity blue diamond corresponds to ET Cha (RECX 15) which has R* = 0.9 R☉ (Siess et al. 2000).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageUsing only the simultaneous values (blue diamonds), we obtain a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient r = 0.73 (p-value = 0.3%

19

) while with all values we obtain r = 0.61 (p-value ⩽ 0.05%). The difference between using all of the data or only the simultaneous data is not significant for the purposes of the correlation. Including all data, we obtain  , where

, where  is given in M☉ yr−1 and the errors indicate 1σ values obtained by the bootstrap method. The correlation is plotted in Figure 4.

is given in M☉ yr−1 and the errors indicate 1σ values obtained by the bootstrap method. The correlation is plotted in Figure 4.

As argued by Johns-Krull et al. (2000), the observed relationship between  and accretion rate is very sensitive to extinction estimates. This is shown in Figure 4, for which the C iv luminosities indicated by the black triangles were calculated using the extinction estimates from Furlan et al. (2009, 2011), for all the targets we have in common with that work. For

and accretion rate is very sensitive to extinction estimates. This is shown in Figure 4, for which the C iv luminosities indicated by the black triangles were calculated using the extinction estimates from Furlan et al. (2009, 2011), for all the targets we have in common with that work. For  and

and  the correlation is weakened when using the Furlan et al. (2009, 2011) extinction values: the value of the Pearson's r is 0.44, with p-value = 5%.

the correlation is weakened when using the Furlan et al. (2009, 2011) extinction values: the value of the Pearson's r is 0.44, with p-value = 5%.

The extinction values we adopt in this paper come from a variety of sources, but a significant fraction come from Gullbring et al. (1998, 2000). They argue that the colors of the WTTSs underlying the CTTSs are anomalous for their spectral types, which biases the near-IR extinction estimates. They obtain the extinctions reported here by deriving models of the UV excess in CTTSs. For other stars, we have adopted extinction estimates based on spectroscopic observations of the accretion veiling, when possible. The extinction values from Furlan et al. (2009, 2011) are obtained by de-reddening the observed near-infrared colors until they match the colors for the target's spectral type. They are significantly larger than the values we adopt in this paper, resulting in larger estimates of the C iv luminosity. Differences in the extinction estimates can have a substantial impact in the adopted flux, as a 10% increase in the value of AV results in a 30% increase in the de-reddened C iv line flux.

Figure 4 also shows the relationship between accretion rate and C iv luminosity derived by Johns-Krull et al. (2000, their Equation (2)) assuming that all stars have a radius of 2 R☉. They obtained their relationship based on the accretion rates and extinctions from Hartigan et al. (1995). Both of those quantities are higher, on average, than the ones we adopt here, and so their correlation predicts larger accretion rates. Note that the relationship from Johns-Krull et al. (2000) is not defined for stars with excess C iv surface fluxes smaller than 106 erg s−1 cm−2.

Overall, there is enough evidence to confirm that for most CTTSs the C iv line luminosity is powered primarily by accretion, and we will adopt this hypothesis here. However, the exact relationship between accretion rate and C iv luminosity remains uncertain. This is not surprising considering the complexity of the processes that contribute to the line flux, as we show in this work. The dominant uncertainty is the exact value of the extinction, which depends on the assumed stellar colors and on the shape of the extinction law in the UV (Johns-Krull et al. 2000; Calvet et al. 2004).

We do not detect a monotonic decrease in the CTTSs C iv luminosity as a function of age, for the range of ages considered here (2–10 Myr). We do not observe a significant difference in the C iv luminosities of the TDs as compared with the rest of the sample, consistent with the results from Ingleby et al. (2011) who found no correlations between FUV luminosities and tracers of dust evolution in the disk.

5. THE C iv LINE SHAPE

The C iv lines of CTTSs are generally redshifted, broad (with emission within ∼400 km s−1 of the stellar rest velocity), and asymmetric to the red (positive skewness). We will show that none of these characteristics is correlated with the line luminosity or with accretion rate.

5.1. Comparing the Two C iv Lines

If optically thin, both C iv lines form should have the same shape. Differences between the components can help us discover the presence of extra sources of absorption or emission. To exploit this redundancy, in Figure 16 we plot both members of the C iv doublet, with the 1550 Å line scaled to match the 1548 Å one. The scaling is done by matching the line peaks or the line wings from ∼0 to ∼150 km s−1. We expect this scaling factor to be 2 for optically thin or effectively thin emission. However, as we discuss in Section 5.2.4, the opacity characteristics of the broad and narrow line components are different, and the overall scaling factor may not be the best predictor of opacity.

Figure 16 shows that the line wings tend to follow each other closely, at least until about +200 to +300 km s−1, when the 1548 Å line start to bump into the 1550 Å one. The 1548 Å line is usually contaminated by the H2 line R(3)1–8 (1547.3 Å), at −167 km s−1 with respect to its rest velocity (e.g., DK Tau). Figure 16 also reveals examples of extra emission at ∼−100 km s−1 which do not appear in the 1550 Å line (AK Sco, DE Tau, DK Tau, DR Tau, HN Tau A, RU Lup, and UX Tau A). We tentatively identify emission from Fe ii (1547.807, −73.6 km s−1 from the rest velocity of the 1548 C iv line), C ii (1547.465; −139.8 km s−1), and Si i (1547.452 Å, −142.3 km s−1; 1547.731 Å, −88.3 km s−1), for these stars, as responsible for the emission to the blue of the C iv 1548 Å line.

To measure the C iv line flux listed in Table 8 we subtracted the continuum and interpolated over the H2 R(3)1–8 line and the Si i, C ii, Fe ii-complex, when present. The resulting spectrum is then integrated from −400 km s−1 to 900 km s−1 of the 1548 C iv line. We also detect the CO A-X (0–0) absorption band at 1544.4 Å (−730 km s−1 from the 1548 Å line; see France et al. 2011; McJunkin et al. 2013) in a significant fraction of the sample. The wing of the CO absorption may extend to the blue edge of the 1548 C iv line. However, its impact in the overall C iv flux is negligible.

Note that the red wings of each C iv line for DX Cha, RW Aur A, DF Tau, and RU Lup do not follow each other, and AK Sco and CS Cha have extra emission features near the 1550 Å.

For DX Cha we will argue in Section 8 that the peculiar shape of the C iv lines can be explained by the existence of a hot wind.

The strange appearance of C iv lines of RW Aur A is due to a bipolar outflow (see Figure 5). France et al. (2012) show that the H2 lines from RW Aur A are redshifted by ∼100 km s−1 in at least two progressions ([v', J'] = [1, 4] and [1, 7]), as they originate in the receding part of the outflow. In the observations we present here, the C iv doublet lines are blueshifted by ∼−100 km s−1, as can be seen from the position of the 1550 C iv line. This points to an origin in the approaching part of the outflow. The net result of these two outflows is that the blueshifted 1548 C iv line is buried under the redshifted H2 emission. RW Aur A is the only unequivocal example of this coincidence in the current data set. For HN Tau A the H2 R(3) 1–8 line is also redshifted, although the redshift (+30 km s−1) is within the 2σ of the error introduced by the pointing uncertainty (see also France et al. 2012). Therefore, HN Tau A may be another object for which we are observing two sides of the outflow, although the velocities of the blueshifted and redshifted sides do not match as well as in RW Aur.