Abstract

Alpha particles can be detected by measuring the radioluminescence light which they induce when absorbed in air. The light is emitted in the near ultraviolet region by nitrogen molecules excited by secondary electrons. The accurate knowledge of the radioluminescence yield is of utmost importance for novel radiation detection applications utilizing this secondary effect. Here, the radioluminescence yield of an alpha particle is investigated as a function of energy loss in air for the first time. Also, the total radioluminescence yield of the particle is measured with a carefully calibrated Pu emitter used in the experiments. The obtained results consistently indicate that alpha particles generate photons per one MeV of energy released in air at normal pressure (temperature C, relative humidity 43%) and the dependence is found to be linear in the studied energy range from 0.3 MeV to 5.1 MeV. The determined radioluminescence yield is higher than previously reported for alpha particles and similar to the radioluminescence yield of electrons at comparable energies. This strengthens the evidence that the luminescence induced by charged particles is mostly proportional to the energy loss in the media and not very sensitive to the type of primary particle.

Content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

The alpha-induced luminescence of air can be utilized for remote detection of open alpha emitting radioactive sources [1–5]. The motivation for the optical approach arises from the fact that luminescence light can convey decay information far beyond the range of an alpha particle. This enables remote and safe detection of highly hazardous alpha emitters by photon counting devices and sensitive cameras. Since the optical method is not limited by the range of the particle, significant advancements can be achieved in decontamination and safety inspection applications. Furthermore, it is possible to monitor contamination through ultraviolet (UV) transmitting materials such as plexi and lead glass, without breaching the containment [5, 6]. The technique has been demonstrated in field tests by independent research units and it has the potential to evolve into an industry-standard procedure in the future [3–5, 7]. An important design parameter for all promising applications is the luminescence efficiency of air, which is widely studied for electrons, but publications regarding alpha particles are few in number.

Light emission induced by alpha particles in air was first observed by Sir William and Lady Huggins in the early years of the 20th century [8]. At the time, the emission spectrum was recorded with a film spectrometer and found to be coincident with the band spectrum of nitrogen. It was concluded that the radioluminescence mostly originates from 2P and 1N band systems of molecular and ionized nitrogen, which are known to emit light in the spectral region from 300 nm to 430 nm [9]. In the 1950s, the recently invented photomultiplier tube (PMT) catalyzed further studies on the scintillation properties of different materials and the effect was widely examined in noble gases but also in nitrogen and air [10–12]. One of the earliest reports to quantify the number of photons generated by a single alpha particle in air is described by Duquesne and Kaplan in 1960 [13]. The result of 60 photons per one 4.6 MeV particle was achieved with a PMT equipped with a quartz window. More recently in 2004, Baschenko used UV-sensitive film for the measurement which resulted in 30 photons per alpha particle from a highly active Pu emitter [1]. In 2011, Chichester and Watson concluded that the yield is between 20 and 200 photons per one alpha particle in the 4–5 MeV energy range [2]. In this retrospect, quantitative studies on alpha particle luminescence yield are fairly rare, mainly due to the fact that practical implementations for detection purposes have only recently started to emerge.

The physics of electron-induced luminescence in air is widely studied by the astrophysics community [14–20]. The comprehensive set of knowledge acquired from electron experiments can be directly applied to alpha particle studies, since emission characteristics and de-excitation of nitrogen molecules are independent of the preceding interactions. However, the excitation efficiency should be studied independently for alpha and beta particles, since there are differences in the mass and charge of the initial particle. It is noteworthy that the luminescence is mostly induced by collisions with secondary electrons and nitrogen molecules in both cases [20].

In this work, the absolute radioluminescence yield of alpha particles is studied with two conceptually simple experiments which are designed for accuracy and repeatability. First, the optical emission from a calibrated point source is observed with a PMT as a function of source-to-detector distance (SDD). This result is then used to calculate the total luminescence yield along the alpha particle track. Second, a passivated implanted planar silicon (PIPS) detector is utilized to record a UV-gated alpha spectrum. This enables the measurement of luminescence yield as a function of deposited energy, reported here for the first time. In addition, a brief supplementary experiment was conducted to investigate the effect of humidity on the luminescence yield. The obtained results are summarized to give a precise and up-to-date estimate of alpha particle radioluminescence yield in air.

2. Experimental methods

2.1. Calibrated alpha emitter

The Pu alpha emitter used in the experiments was prepared from a nitrate solution by electrodeposition on a steel planchet. The work was conducted by the radiochemistry laboratory of the Finnish Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority and the solution was certified by the Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements. The solution contained mostly Pu and had minute amounts of Pu, Pu, Pu, Am, and Pu as impurities. The 15 mm diameter planchet was uniformly covered to a 1 mm distance from the edge with the active material, and it was left uncoated to achieve a sharp energy peak and uniform emission of alpha particles.

The alpha source was carefully studied by alpha and gamma spectroscopic measurements to verify the surface emission rate and the amount of active material. The alpha measurement was performed with a PIPS detector in a vacuum and the gamma analysis was conducted with an HPGe detector (Canberra, BE5030). A summary of the results is presented in table 1. The activity of Pu is estimated from the atomic ratio of Pu/Pu in the original solution since, as a weak beta emitter, it could not be measured directly. It is assumed that the atomic ratio of the original solution is not affected by the electrodeposition process.

Table 1. Activities of different isotopes in the emitter. The method of measurement is indicated in the first column. Note that the activity of Pu is calculated from the atomic ratio of Pu/Pu in the original solution.

| Method | (kBq) | (kBq) | (kBq) | (kBq) | (kBq) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIPS | |||||

| HPGe | — | — |

As presented in table 1, the vast majority of alpha particles are emitted by Pu. The total alpha activity of the emitter is , which is calculated according to the PIPS measurements, since they are the best to represent the surface emission rate. In addition, the data imply that activity-weighted average alpha decay energy of the emitter is 5.1 MeV. The plutonium source also contains a significant quantity of beta-particle-emitting isotope Pu. Fortunately, the total energy deposited to air by these low-energy beta particles (average energy 5.2 keV [21]) is over 2600 times smaller than the energy deposited by the alpha particles. Thus, their contribution to the total light emission can be neglected.

2.2. Measurements with calibrated point alpha emitter

The total luminescence yield along the alpha particle track can be measured by placing a single-photon sensitive detector at a known distance from a radiation source. The alpha particles ionize air in a half-sphere that has a radius equivalent to their range in air. This scintillating hemisphere can be observed as an optical point source from a sufficient distance. The emission of photons is isotropic, and therefore, the photon flux spreads evenly over the full solid angle. Under these conditions, the luminescence yield can be measured from every direction that is not subtended by the source itself.

In this experiment, a channel photomultiplier (Perkin Elmer, MP-1982P) with a low-noise bi-alkali photocathode was used to count the luminescence photons. This module exhibits an extremely low dark count rate (below 0.5 s) making it suitable for measuring low photon flux signals while still maintaining a large, 15 mm diameter active area. The detector is sensitive to photons at a wavelength range from 165 nm to 650 nm, and the quantum efficiency is calibrated by the vendor to be 18.3% at 410 nm. The average quantum efficiency for nitrogen emission was estimated to be 20.3%. The value was obtained by adjusting the catalogue spectral response curve with the efficiency reported by the vendor and weighting the value with the relative intensities of the main nitrogen emission bands. The emission intensities are quoted as in the work of Ave et al [9] and these are presented together with the quantum efficiency curve in figure 1. A traceable, end-to-end calibration of the photon counting module was not performed, but the spectral response data provided by Perkin Elmer are in good agreement with state-of-the-art calibration techniques [22].

Figure 1. Relative intensities of nitrogen emission bands and smooth quantum efficiency curve of the photomultiplier tube. The intensities of nitrogen bands are measured by Ave et al [9].

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFor the measurements, the radiation source was placed on a steel pole so that the PMT observes the scintillating volume from the side (see figure 2 (a)). This geometry minimizes the contribution of the photons that are reflected from the emitter planchet to the detector. Furthermore, the emitter pole was attached to a remote-controlled slide so that the SDD could be varied from 200 mm to 600 mm. The whole assembly was enclosed in a cardboard box to protect it from external light. The inner surfaces of the box were covered with matte black aluminum foil to prevent the reflection of light. Also, a 30 mm iris was positioned in front of the photomultiplier to further reduce the contribution of scattered photons. The iris was positioned close enough to the detector (25 mm) for the photocathode to act as a limiting aperture (field stop) in this system. Lastly, a remote-controlled shutter plate was placed in front of the iris to enable the measurement of the detector dark count rate.

Figure 2. (a) Photon counting setup with variable source-to-detector distance. (b) Setup for UV-gated alpha energy measurement. The distance between emitter and PIPS detector was adjustable.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image2.3. Measurements with alpha-UV coincidence

The radioluminescence yield as a function of alpha particle energy loss in air was measured using alpha-photon coincidences. The alpha emitter was attached vertically to a holder on a translation stage, and a PIPS alpha detector was placed on the opposite side of the emitter planchet (see figure 2(b)). Both the emitter and the detector were covered with a circular diaphragm made of black foil (Acktar, Vacuum Black) to mitigate reflections. The 5 mm diameter aperture of the diaphragms collimated the alpha beam to a cylindrical shape and therefore, the size of the optical source was significantly smaller than given by the total light-yield measurement.

The PMT was placed at a 150 mm distance from the center of the optical source. The distance was chosen so that the point-source approximation is valid while maintaining a sufficiently high photon count rate. A 10 mm diameter aperture was placed close to the PMT window to reduce the acceptance angle of the detector. The distance between the surfaces that cover the alpha emitter and the PIPS detector was adjustable from 3 mm to 53 mm (figure 2(b)). As in the first experiment, the whole measurement setup was enclosed in a light-tight box with black matte aluminum foil lining the inner surfaces.

The alpha detection system consisted of a PIPS detector (Canberra) and a multichannel analyzer. This instrumentation was used to record the alpha energy spectrum in both singles and gated mode. The gate signal was generated from the digital PMT output pulse by introducing a short delay and extending it to 1 μs. The acquired spectra were analyzed to reveal the average count rate and mean energy of detected alpha particles. At each measured point, the calculation was limited to those particles that were included in a 200 keV wide energy window around the main alpha peak.

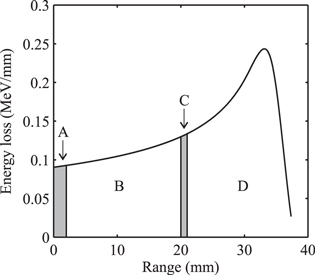

The energy loss along the track of an alpha particle is described by the Bragg curve, presented in figure 3. This curve was used to estimate the amount of energy that is absorbed in the field of view of the PMT. The photons generated just after the emitter and just before PIPS are not visible to the PMT due to mechanical collimation of the alpha beam. The amount of energy that is producing detectable luminescence emission was calculated by subtracting the losses and the measured residual energy from the assumed initial particle energy.

Figure 3. Principle of alpha particle energy loss calculation in UV-gated PIPS measurement. Short ranges just after the emitter (A) and before PIPS (C) detector are not visible to the PMT due to mechanical collimation of the alpha beam. The residual energy (D) is absorbed in PIPS detector and used to estimate the energy loss (B) in the field of view of the PMT. The Bragg curve shown here represents the energy loss of a 5.1 MeV alpha particle in air and it is calculated using the stopping power reported in the NIST Astar database [23].

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image3. Determination of radioluminescence yield

3.1. Radioluminescence yield of calibrated point alpha emitter

Alpha-particle-induced photons are emitted in an isotropic manner from the vicinity of the radiation source. This point emitter can be approximated as an optical point source if observed from a long distance. Under this assumption, the probability that one alpha particle is detected with the PMT is

Here, Y represents the luminescence yield in photons per particle, QE is the detective quantum efficiency of the PMT, and is the geometrical efficiency of the setup. The latter can be estimated from the ratio of detector window area and the surface area of a sphere that has a radius equivalent to SDD. The absorption of air at these wavelengths is low and can therefore be neglected in the analysis.

The probability of detection can be used to estimate the photon count rate in an experiment where an alpha emitter is observed with a PMT. Now, the alpha emitter surface emission rate has to be included in the equation together with the background count rate . The total count rate is expressed as

This equation can be solved for Y to estimate the luminescence yield. In this work, the equation is fitted into experimental data using Y and as free parameters.

The measured net photon count rate (i.e. corrected for the dark counts) is shown as a function of SDD in figure 4. At each point, the gross and dark count rate were determined separately with the help of the remote-controlled shutter. The acquisition time was adjusted so that the combined statistical uncertainty of the net count rate is less than 0.5% at each point. A nonlinear least squares method was used to fit equation (2) to the data. The resulted yield was 99 photons per alpha particle, and the background count rate was 2.7 pulses per second. This implies that the 5.1 MeV alpha particles observed here produce 19.4 photons per each MeV of energy released in air. A detailed uncertainty analysis is presented in section 4.

Figure 4. Photon count rate as a function of source-to-detector distance. The values are corrected for the detector dark counts. Inset: net photon count rate multiplied by the square of SDD. The constant value verifies the applicability of equation (2).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe measured points and the fitted curve are in good agreement in figure 4. This verifies that equation (2) describes the signal evolution reliably as a function of SDD. It is necessary to notice that the presented count rates are free from the intrinsic detector background but not totally free from the contribution of scattered photons. These photons give rise to the background term in equation (2) and its average value is revealed by letting float freely in the fitting process. With this method, the effect of reflections is minimal to the value of the luminescence yield estimate Y. The weakness is that only the average count rate of reflections is evaluated and therefore, it is necessary to assume that the contribution is similar irrespective of the position of the radiation source. The validity of this approximation can be tested by using the product of true net count rate and the square of the SDD as a figure of merit. The inset in figure 4 shows the product over the span of different SDDs and the value stays constant. This verifies that the point source approximation is valid and the amount of reflections is reliably estimated.

3.2. Radioluminescence yield as function of deposited energy

In the gated setup, the PIPS detector is triggered only after the detection of an optical photon. This enables the coincident measurement of luminescence yield and the residual kinetic energy of the particle that is absorbed in the detector. With this information, it is possible to estimate the energy that the trigger particle deposited to air. The calculation is based on knowledge of the initial alpha particle energy and stopping power of air, acquired from the NIST database [23]. In this experiment, the energy loss in air was adjusted by varying the emitter-to-detector distance with a linear translation stage. To demonstrate the effect of UV gating and distance adjustment, the energy spectra of alpha particles in the first and last measurement point are shown in figure 5. The detection efficiency of the PMT was calculated from this information by dividing the alpha peak areas in UV-gated and un-gated singles alpha measurement. The alpha particle luminescence yield is related to this detection efficiency with equation (1).

Figure 5. The alpha particle energy spectra in the UV-gated experiment. Both the singles and UV-gated spectra are shown for two measurement points which correspond to the longest and shortest alpha particle path length in air.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIt is noteworthy that this experiment does not require emitter activity calibration and no assumptions are made on the geometrical distribution of emitted particles. All the observed alpha particles are confined to the cylindrical volume by virtual collimation. The particles that are detected by the PMT but do not hit the PIPS detector are not affecting the result, since they are not included in either spectrum. Instead, a random coincidence between an uncorrelated photon and alpha particle can be recorded. The rate of these events is described with the equation

where is the count rate of PMT, is the singles count rate of PIPS detector, and τ is the length of coincidence window. According to this model, the expected contribution of random events was always less than 2% of the total count rate at each measured point. The equation was applied in the analysis to correct the measured data for random coincidences.

The photon detection efficiency was measured at nine different emitter-to-PIPS-detector distances, which all represent different energy loss in air. This information was used to calculate the luminescence yields at corresponding energies. Only the part of the alpha track that is visible to the PMT is included in the energy loss calculation (see section 2.3). The resulted data are presented in figure 6 as a function of deposited energy. Linear regression shows that the number of generated photons increases with a slope of 18.5 photons per each MeV of energy released. The constant term in the regression analysis is 1.7 photons per alpha particle which may be attributed to the scattering of photons and systematic uncertainties in the energy calculation. The result is in good agreement with results obtained in section 3.1, where the yield was measured to be 19.4 photons per MeV. Therefore, it can be concluded that the energy transfer into optical photons is linear in the whole examined range from 0.3 MeV to 5.1 MeV.

Figure 6. Number of photons as a function of alpha particle energy loss in air. The slope of the fitted line is 18.5 photons per each MeV of energy released in air.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image3.3. The effect of gas atmosphere

During the experiments above, the humidity, temperature and pressure of the laboratory air were monitored with appropriate instruments (Vaisala, HMP75 and MKS Instruments, A900 PiezoSteel). The relative humidity was measured to be at a C temperature and the total pressure was close to 99 000 Pa. The variation in temperature and pressure in indoor environment is expected to be too small to have significant effect on the radioluminescence yield. However, humidity can affect the results, since water molecules, together with oxygen, are effective quenchers for excited nitrogen molecules [15].

In this work, the effect of humidity was briefly investigated with a similar setup as described in section 3.1. Here, a 13 kBq Am alpha emitter was placed in an air-tight steel casing and the photon flux was measured through a UV-fused silica window with the PMT. The casing was evacuated with a vacuum pump between experiments and a mass flow controller was used to provide gas flow through the chamber to ascertain gas purity during acquisition. The dimensions of the chamber were too small for absolute yield measurements, but the relative signal strength was recorded in three different gases including laboratory air (RH 46%), dry air (21.4% O in N, Aga gas) and pure nitrogen (99.9999%, Aga gas). All the gases were measured at 21 C temperature.

The photon count rate of this experiment was intentionally kept low by adjusting SDD to 15 cm and by using a metallic collimator on top of the emitter to reduce the number of particles reaching the field-of-view of the detector. Furthermore, the metallic collimator provided a shield from gamma rays which could induce scintillations in the silica window. The SDD used here ensured that the average number of photoelectrons created per particle was below 0.04 in nitrogen. In this case, the Poisson statistics prove that more than 98% of detected events consist of single photoelectron emissions. Hence, the linear dependence of single photon count rate and photon yield is well justified for all the gases in the analysis. The background-subtracted net count rates are presented in table 2.

Table 2. Relative light yield in different gas atmospheres at 21 C temperature.

| Gas | Net count rate (s ) | Relative signal |

|---|---|---|

| Room air | 1.00 | |

| Dry air | 1.07 | |

| Nitrogen | 6.00 |

The obtained results confirm that the strongest luminescence is observed in nitrogen, which is due to the lack of humidity and oxygen. Secondly, dry air provides 7% more signal than humid room air. However, the difference may be even higher, since the dry air used here had slightly elevated oxygen content. More detailed studies on quenching properties can be found in the literature [15, 20].

4. Uncertainty analysis

The uncertainties of the experiment consist of a systematic and a statistical part. The statistical error in the photon counting experiment of section 3.1 was kept below 0.5% by using long acquisition times. In the gated experiment, a small statistical uncertainty arises from the random occurrence of alpha-photon coincidence events. The total uncertainty due to statistical factors is expected to be small, since best-fit methods are used to unveil the luminescence yield in both analyses.

The most significant systematic uncertainties result from the calibration of the photon counting unit and from the determined geometrical factors. The detective quantum efficiency of the PMT is assumed to have an uncertainty of . This figure considers the accuracy of typical absolute calibration methods but also leaves marginal for errors that arise from the multispectral composition of nitrogen emission [24]. The geometrical aspects include the radius of the detector active area and source-to-detector distance which together define the photon collection efficiency. In addition, the calibration of the alpha emitter introduces a small uncertainty together with the assumption of uniform alpha emission. However, this does not affect the UV-gated measurement as the optical efficiency is estimated from the ratio of detected alpha particle events. Each systematic uncertainty is presented in table 3 and the total is the sum in quadrature of all the contributions.

Table 3. Systematic uncertainties of the experiments.

| Source | Uncertainty | Yield uncertainty (3.1) | Yield uncertainty (3.2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| QE of PMT | |||

| Radius of detector area | |||

| Source-to-detector distance | |||

| Surface emission rate | — | ||

| Total |

In the previous analysis, the photon absorption is considered to be negligible at these wavelengths and short distances. Also within the ionization volume, the absorption is small, since excited molecules are rare and short-lived. Reflections from the emitter planchet are not included because the surface is oriented perpendicularly to the detector window and its reflectivity is fairly low. The good agreement of results further implies that neither emitter reflections nor beta luminescence are a concern in section 3.1. In conclusion, the most significant uncertainty is related to the calibration of the photon counting module.

5. Discussion

On average, the two different experiments show that each MeV of energy released creates 19 photons in normal air with 43% relative humidity. These photons originate mostly from 2P and 1N band systems of nitrogen and they are emitted in the near UV region from 300 nm to 430 nm. The total conversion efficiency from kinetic energy into luminescence is if a representative wavelength of 350 nm is chosen for all photons. The obtained radioluminescence yield is higher than in the previous studies [1, 13, 25].

It is known that the role of the primary particle is minor in the final excitation of nitrogen molecules. The absorption of charged particles in air is a process where the initial kinetic energy is transferred to low-energy secondary electrons via a cascade of collisions. These electrons induce the luminescence and their emission cross-sections are known to peak at low energies. The major bands of 2P system are best excited by 15 eV electrons and the emission cross-section effectively vanishes for energies exceeding 100 eV [26, 27]. On the other hand, the excitation of 1N(0,0) band is most efficient at 100 eV and has some tail to above 1 keV [27]. Despite this, the most photons are due to low energy electrons and 2P bands, since the contribution of 1N system is small in the total light yield under normal pressure. For these reasons, it is apparent that luminescence is excited only after a significant number of electron–electron interactions.

The light yield in dry air would be 20 photons per one MeV of energy released, when the measured luminescence efficiency is corrected for the humidity of room air. For comparison, recent studies on electron beams in dry atmospheric air estimate that the luminescence efficiency is between 17.6 and 20.8 UV photons per one MeV of energy released [17–19]. These values are obtained with electron energies ranging from 0.85 MeV up to 50 GeV, and it has been reported that the conversion efficiency is constant over a broad energy range [28]. Given that alpha particles release comparable amounts of energy and through similar interactions as electrons in cited investigations, the similarity of the results is evident. Consequently, these results strengthen the evidence that luminescence yield at high particle energies is first and foremost proportional to the energy loss in air.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to accurately measure alpha particle radioluminescence yield in air. To do so, two independent experiments were conducted, consistently indicating that alpha particles generate photons per one MeV of energy released under typical indoor conditions. A linear dependency between photon yield and energy loss is well adopted for electrons in astrophysics and here, it is experimentally confirmed for alpha particles in the studied energy range from 0.3 MeV to 5.1 MeV for the first time. Furthermore, the determined radioluminescence yield is on the same level with the results of recent electron beam experiments and thus, higher than previously reported for alpha particles. The obtained results are essential for all emerging applications that utilize the UV method for the detection of alpha radiation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kaisa Vaarala for preparing the alpha emitter used in this work, and Seppo Klemola and Roy Pöllänen for the thorough calibration of the emitter. The work was supported in part by Alphamon, a project mainly financed by Tekes, the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology. Other Alphamon funders are Outokumpu Stainless Oy, Rautaruukki Oyj, FNsteel Oy Ab, Senya Oy, Mirion Technologies (RADOS) Oy, and Environics Oy.